KATRIINA HELJAKKA

University of Turku

Abstract

In this essay, I describe how adult fans of the Star Wars universe engage actively in world-building through world-play. What distinguishes world-play from world-building, as proposed by Wolf (2012), is an understanding that adult toy play involves more than mere collection of toys, the most prominent concept in both hobbyist and theoretical writings on adults’ relationships with toys. In my analyses of visual and narrative data collected with adults, I have concentrated on profiling the types of adults who play with toys (Heljakka, 2013) and mapping out popular play patterns and motivations to play in reference to mass-produced toys (e.g., Heljakka, 2012; 2013; 2015). The essay at hand aims to investigate how adults’ play with Star Wars toys also entails elements of world-building in terms of both imaginative and spatially emerging object play patterns. Moreover, my study explores the employment of narratives from the original Star Wars films as texts and a source for contemporary fan play. Focus will be given to how the story-worlds of George Lucas, now imagined further by Disney and its storytellers, impact the current world-playing practices of Star Wars fans.

Keywords: Adult toy play, photoplay, re-playing, Star Wars, toys

******

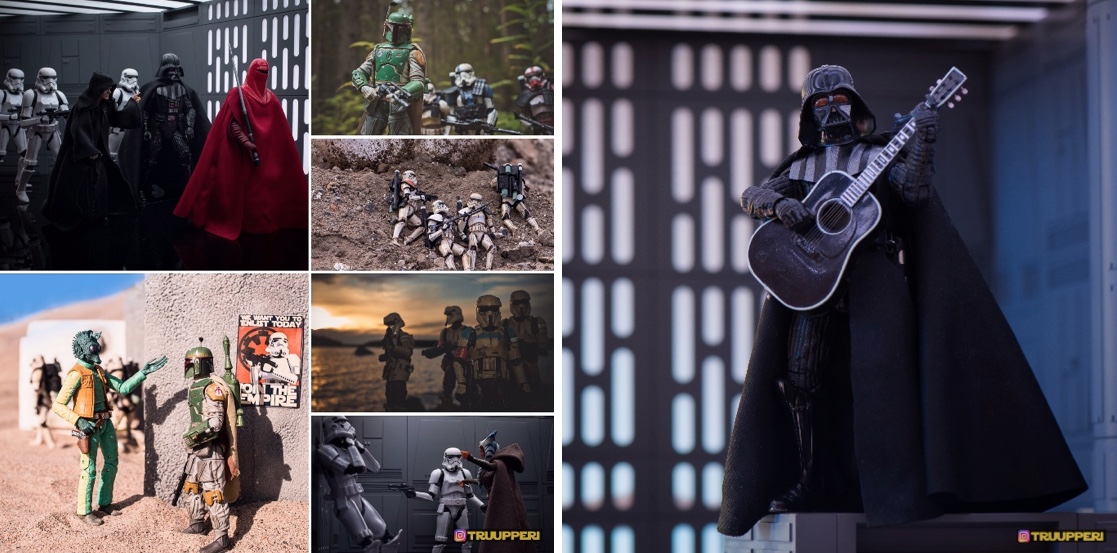

Image 1. “Before the ‘selfie’ there was the ‘Stormie’”, photoplay by Truupperi (Janne Mällinen).

Introduction

In the press release materials related to the first Star Wars film, the motion picture medium is referred to as “the most magnificent toy ever invented for grown men” (Dingilian, 1977, Production notes “Star Wars”, n.p.). According to Dave Okada in The Toys that Made Us (2017), “something can be played with, if it is toyetic.” Star Wars is a transmedia phenomenon that has represented toyetic qualities since the launch of its first film.

Because of its often open-ended and free-form nature, play is difficult to quantify and analyze (Panton, 2006). Nevertheless, toys invite play and suggest play performance (Heljakka, 2017). As explained by Rehak, an object-practice perspective brings physical artifacts and processes to the fore (Rehak, 2013). Today, transgenerational interactions with toys, a physical medium, are increasingly intertwined with not only transmedia universes but also screen-based activities, mostly photographs or videos of play scenarios. In this way, 21st century toy play may be viewed as an oculocentric, technologically enhanced, and story-driven practice.

Contrary to common belief, in addition to collecting, adults also engage in manipulative play with contemporary character toys (or toys with faces) such as action figures, dolls, and soft toys. During this playing, many play patterns can emerge in various playscapes. One such type of play is multidimensional interaction with action figures, which I am referring to here as world-play. In the context of this essay, instead of using the terms “collectors,” “builders,” or “geeks,” I have chosen to use the term world–players. Adult world-players are the core of my investigations of adult explorations and activities related to world-building.[1]

Star Wars is certainly not the only transmedia phenomenon that invites fans to engage in many kinds of play activities. However, it is a unique case considering the size of its fan base; Star Wars toys are argued to be the most popular (i.e., commercially widespread) toy series of all time. Over the long history of the franchise, Star Wars characters have been developed into many kinds of different types of character toys (e.g. Kenner, Hasbro, JAKKS, LEGO, Funko Pop!, etc.), which provides an interesting starting point for this analysis of world-play. According to Panton, “looking at Star Wars play helps us understand the types and level of this interaction and some effects that Star Wars has had on society” (Panton, 2006, p. 195).

This essay investigates fans’ contributions to the Star Wars expanded universe by exploring fan-conducted photoplay (i.e., creative and socially shared toy photography). It aims to highlight recent directions and developments in the narrative content of photoplay related to Star Wars. The main goal of the essay is to shed light on Star Wars fans’ willingness to mimic and world-play Star Wars through means such as official toys as well as the personal, creative component of play (i.e., imagination and skill in manipulation of materials) and to discuss whether or not different kinds of Star Wars toys launched during different times have an impact on how the characters are played with in relation to canonical texts. To do so, I will investigate fan-created photoplays of Star Wars presented on Instagram in relation to the original trilogy and current trends that draw inspiration from the expanded universe. The goal is to demonstrate the multifaceted and transmedial nature of adults’ use of Star Wars, toys, and the various world-playing activities connected to these media.

Image 2. Variations of a Leia action figure. Image 3. Variations of a vintage Rebel soldier

photographed by TOY VILLAIN, a vintage toy collector from Malmö, Sweden.

Methodology

Although observing other peoples’ toy collections and artists “toying” with playthings on social media can be seen as both acceptable and enjoyable, adult toy enthusiasts themselves are rarely open about play activities with their own toys. Instead, information on adult toy play must be sought in other types of documented play: in socially shared photographs of toys, or photoplay; “toy stories” shared on blogs or collected through interviews; and other possible forms of play knowledge (Heljakka et al., 2017). In order to understand the nature of adult world-play with toys, the player perspective must be taken into account. The research presented in this essay is grounded in multiple readings and analyses of the manifestations of adult toy play in photoplay (or toy photography) displayed on social media (e.g., Instagram) and supplemented with participatory observation at toy conventions. An online survey with questions about Star Wars fans’ object interactions and relationships with the story worlds of Star Wars was conducted in fall 2017. The author recruited participants at the Hothcon 2017 event in Helsinki, Finland in December 2017, and the survey was spread through snowballing on Facebook groups such as the Star Wars Finland Facebook page. Altogether, 40 respondents joined the survey. Further, a visual analysis of Star Wars-related images on Flickr, Instagram and the Facebook page for the Finnish group “Collectors of figures and movie memorabilia” was performed during December 2017. Hundreds of images were analyzed as background for the interviews and used as tools for constructing questions. The interpretative framework produced by this contextualization was also analyzed.

Using this interview contextualization process for both research materials and methodology, my goal is to answer the research question: how do adult toy players who are fans of the Star Wars universe actively engage in world-building through world-play? By presenting the results of the multi-methodological study presented here, I aim to demonstrate new evidence regarding adult world-play in connection with Star Wars-related toys.

Image 4. “Now in stock, Lego Sandtrooper and Dewback.” Photograph by HeadHunter Store.

In a toy galaxy, so close… Adults as collectors of Star Wars toys

The interviewees in my study describe Star Wars affectionately as their “#1 fictional franchise of interest”: “It’s a huge part of my life, has been for years. Gave me an alternative world to submerge myself when times in the childhood family were tough and intolerable.” Toys, like the original movies, books, comics, and cosplay, comprise a significant part of Star Wars fandom. In fact, Star Wars has the largest collector base of any (toy and entertainment) brand (Geraghty, 2006).

The Expanded Universe describes ‘the multiple officially licensed stories emerging from the storyworld established in the six Star Wars feature films’ (Harvey, 2015, 145). Toys were some of the first objects to be launched in the expanded universe of the original films. As Wookiepedia mentions, “The term ‘Expanded Universe’ was first used with Kenner’s assortments of action figures based on the various Star Wars novels, comic books, and video games.” To date, over one billion Star Wars toys have been sold (The Toys that Made Us, 2017), the most commonly collected of which are action figures (The Force of Three Generations, 2011). In addition to the original action figures produced by Kenner (later acquired by Hasbro), several toy lines have involved the iconic characters. The aesthetics of these toy lines already represent world-play with Star Wars in that toy designers and companies are modeling new versions of familiar characters. Lego Star Wars is a line of Legos that incorporates imagery from the Star Wars saga. Originally it was only licensed from 1999–2008, but the Lego Group extended the license with Lucasfilm Ltd. Angry Birds Star Wars is a puzzle video game that incorporates characters from the Star Wars franchise into the Angry Birds video game series, launched on November 8, 2012. What started as a game later expanded to a line of plastic and plush toy figures. Finally, Funko Pop! is a series of cute and “positively intimidating array of traditional model[s]” [2] based on a variety of characters from popular culture, including those from Star Wars, that attracts a transgenerational audience. Since Disney acquired Lucasfilm, the selection of merchandise has grown even further:

The amount of merchandise has been pumped through the roof, and then some. Star Wars is now omnipresent – you can get anything your heart desires with a Star Wars twist. Disney is banking on the fact that the series is beloved. In fairness, I don’t think all the fans mind it so much, either, it just means there are more opportunities to enjoy being a Star Wars fan in ways that may not been available in the past. (Male respondent, anon.)

Another fan suggests that:

Disney wants fans as engaged in the franchise as possible, and is cranking out new ways to interact with the Star Wars world. As a fan, the new and expanded array of opportunities to explore and immerse oneself in the Star Wars universe in completely unprecedented ways, and Disney definitely has the capital necessary to develop these experiences. (Male respondent, anon.)

Fans also appreciate changes in the universe regarding characters: “I love it that the Star Wars world has included women and non-Caucasian people better. There are also other people than white men in the universe, after all! :)” (Female respondent, anon.). One female respondent (pseudonym “faerierebelfaerierebel”) says: “It has not really CHANGED, but IMPROVED as [the role of women] and POC have been elevated. Female characters have been elevated especially when considering The Last Jedi, thanks to nonexistent Rey-related merchandise!”

In earlier studies, the author profiled adult toy players in four subgroups; collectors, artists, designers and everyday players (Heljakka, 2013). In the interviews, fans mentioned the agency and ownership that emerge through collecting, which is an important part of being a fan for one female respondent (pseudonym “sieni”): “From the start, collecting has been one of the biggest parts for me, like in many other of my fandoms.” John Tenuto, a professor of sociology and a Star Wars collector, believes that, for collectors, toys “are the tangible symbol for their love of what isn’t real, that has no natural element. It’s a human experience and need to touch and to feel and to see a thing in order for it to have a meaning. Otherwise it is just an abstraction” (The Toys that Made Us, 2017).

Often, mature toy “enthusiasts,” as they call themselves, identify as collectors. For example, a male respondent (anon.) says, “[The most important aspect of my Star Wars fandom is] submerging into the world of Star Wars thru movies and having some piece of it by collecting the toys.” The goal-oriented quality of collecting is an easily understood aspect of adult toy activities for non-fans and researchers. “Toy-collecting adult” is a recognized, cultivated, and widespread term used in reference to mature toy enthusiasts in the Western world. Toy collection has a tangible dimension (e.g., size and quality) that is communicable to an audience through, for example, photographic evidence (Heljakka, 2016). Lucasfilm has acknowledged mature user groups as collectors of Star Wars toys:

Author: How consciously are new Star Wars toys developed with the adult player in mind? Howard Roffman (Lucas Licensing): The adults would certainly not admit to playing with the toys. When the products are right for kids, the products are also right for adult collectors.[3]

Collecting as a formalized type of play behavior and a sub-category of object play can be further categorized in terms of its aims. The toy industry recognizes collectors as the mature audience for toys that is expected to invest in collectible items, which are often more expensive, limited in quantity, and more fragile. Often, the collection of toys is motivated by adults’ nostalgia. Horsley (2006, p. 187) writes, “…these first figures became reverend objects representing not only the Star Wars characters, but also the memories and lessons of Star Wars and days gone by.” According to Dean Clayton (interview with the owner of HeadHunter Store), “You’re hunting after the trophies of your childhood, the effigies of your idols.” These “trophies” need not be vintage toys; one faerierebelfemale respondent (pseudonym “faerierebelfaerierebel”) says that her collection includes: Funko POP characters, Rey figurines by Hasbro, LEGO Buildable Figure Rey, a Micro Machines set with Rey’s Speeder bought both online and offline.”

Despite the obvious connection between toys and play, the possibilities of play are often hidden under the guise of collecting. A male respondent (anon.) describes how he acts as a Star Wars fan “offline”: “Reading, watching movies, playing games, ‘playing’ with my collection.” “Playing” in quotation marks is as far as many fans dare to go when describing their interactions with Star Wars objects. Nevertheless, when considering the multifaceted nature of adults’ interactions with toys, it becomes necessary to include the notion of play as engagement with toys involves mental predisposition towards these objects, a playful attitude, and interest in physical manipulation of three-dimensional objects. According to Gray (2010, p. 205), “[e]ngaging with any form of entertainment, particularly of a fictional nature, is a form of play, and thus texts are essentially spaces for play and the reception it inspires.” According to Lancaster (2001), what motivates some fans of media texts is their desire to achieve haptic-panoptic (touching-seeing) control over images (Hills, 2002).

Collecting is a creative act (Hills, 2009), but how does the act of creating manifest in material practices related to toys consumed by adult toy fans? “What you have in your collection identifies your level of fandom,” argues Geraghty (2014, p. 181). I further claim that what you do with your collection defines your qualities as a player (Heljakka, 2017). Adult interaction, creativity, and skill-building with contemporary toys (e.g., Heljakka, 2015) are new areas of research concerning object play practices at a mature age, an emerging phenomenon. Adult object play is a multifaceted, creative, and goal-oriented activity in which materials are manipulated, re-appropriated, and creatively cultivated (Heljakka, 2016).

Developing technologies, including social media, have enriched the culture of collecting by making it possible to simultaneously care for the collection and share documentation of it. Object interactions result from searching for, observing, admiring, and acquiring toys. Despite the increase in digitalization, the collection, arrangement, and display of physical objects has remained a popular pastime. Manipulation, in which toys are explored and then dis-played, is also common. Once-hidden toy treasures are proudly assembled and showcased to the world through unboxing videos, collection run-throughs, play tutorials, and published “photoplay” (Heljakka, 2017). Display of the toys is the initial step of world-playing discussed in this essay.

Image 5. Kenner’s Star Wars figures displayed and photographed by TOY VILLAIN, a vintage toy collector from Malmö, Sweden. Image 6. Display of a collection of various characters, including those from Star Wars, photographed by www.headhunterstore.com.

Re-imagining, re-creating, and photoplaying Star Wars

One of the objectives of the essay is to analyze styles of world-playing with different types of Star Wars toy characters, including the original Kenner action figures and Lego Star Wars characters. What makes Star Wars toy play particularly interesting is its historical longevity; it attracts many transgenerational players, who have different access points to the series and thus play with its universe in different ways. In addition, due to its large fan base, it has enhanced the visibility of adult toy play many other transmedia phenomena; the amount of photographic documentation of Star Wars-related photoplay vastly outnumber that of photoplay with other characters and story worlds.

According to play scholar Thomas Henricks (2008, p. 159), “to play is to create and then to inhabit a distinctive world of one’s own making.” Toy designers and industries related to play[4] a child yearns for sensory engagement and physical manipulation with the toy, while adults enjoy toys from a distance. For example, many adult toy players use toys to decorate living spaces, thus serving as conversational pieces that may communicate information about the adult’s lifestyle. The toy as a displayed item in the home represents communication between the toy and player and between the toy, the player, and a possible audience.

Adult toy play not only occur in the player’s living or working environment, at the main site of the toy collection and base for display but also in public spaces, such as locations at which television series and films were filmed. At these locations, adults engage in photoplay to re-create popular scenes from narratives such as Star Wars. In this way a cult image in the form of a toy is re-played (Hills, 2002) and familiar stories are re-performed (Jenkins, 2010). However, within industries related to play, toys are often considered paratexts (Gray, 2010). In line with Gray’s (2010) idea that popular meanings are developed by audiences, during adult world-play, the plaything as a paratext may come to be associated with storylines not necessarily present in the original text.

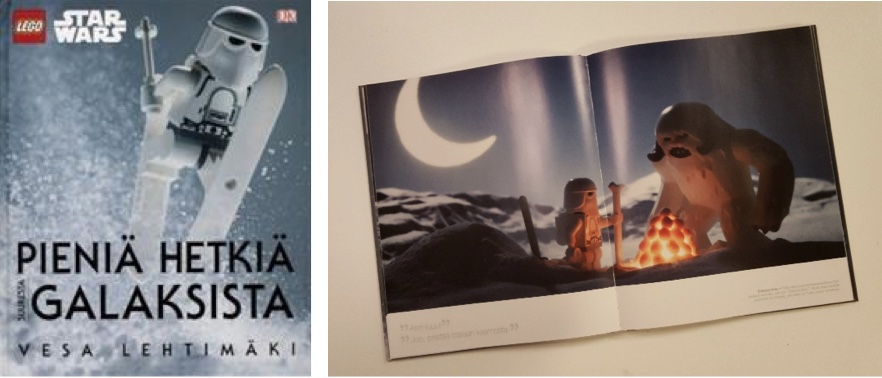

Fans produce texts for other fans, not a mass audience (Fiske, 1992). Photoplaying, as an activity similar to textual productivity (Ibid.) or fan labor (Scholz, 2017), can be performed by professionals or amateurs, who influence each other in many ways. According to Scholz (2017, p. 86), “[m]otivated by mutual respect and acknowledgement instead of monetary compensation, fans show off their skills and knowledge, and celebrate their own creativity.” For example, Finnish photographer and Star Wars fan Vesa Lehtimäki, who engages in experimental photoplay with Star Wars toys, published a mass-marketed book with LEGO® named Star Wars®: Small Scenes from a Big Galaxy. Lehtimäki’s professional photoplay is mainly intended to mimic the style of canonical Star Wars films with LEGOs. Fan world-playing with Star Wars toys often follows a similar path.

Image 7. Finnish photographer Vesa Lehtimäki’s photoplay book includes richly imagined and staged scenarios featuring familiar Star Wars characters. Image 8. “Erämaan kutsu” [“Call of the Wild”], ‘a tribute to Jack London style storytelling’ in the Finnish edition of the book, p. 89.

There is a strong belief that toys with connections to narratives presented in other media, such as TV series and films, diminish creative play (and thus, lack play value) as it is believed that children only repeat the scenarios presented in these media (see, e.g., Kline, 1993). However, players of all ages constantly demonstrate their ability to challenge (and even subvert) suggested backstories (Heljakka, 2016). As Geraghty (2006, p. 217) writes, “collectors all over the world dip in and out of the imagined fantasy world of Star Wars, adding to and expanding the universe created by Lucas.” This becomes apparent when investigating the results of toy play, such as world-play activities regarding Star Wars.

According to Samutina (2016), fan fiction may be understood as a form of world-building. The production of fan fiction is a creative practice undertaken in combination with toy activities such as photoplay, a new form of adult play (Heljakka et al., 2017) that Godwin (2015) refers to as “photostories” and categorizes as “fannish fiction.” In my own research[5], I use the term photoplay to refer to photographic play (e.g. toy photography). Using visual means of representation in parallel to other object play patterns, such as posing or displaying the toy characters or creating dioramas seems to be one of the most popular play patterns among mature toy users. The results of photoplay sometimes also allow the researcher to analyze the personal component of play with contemporary toys (here, Star Wars toys).

Technology has impacted the way in which children—and adults—play (Panton, 2006). For example, use of technologies such as digital cameras, which enable toy photography (photoplay; see, e.g., Heljakka, 2012) or photostories (Godwin, 2015) as well as films involving toys, characterize contemporary play among both children and adults. In addition, mediated or screen-based toy play involving mobile technologies in object play is growing in popularity (Heljakka, 2016).

Contemporary Western play is increasingly dependent on contemporary media texts as a starting point for play (Panton, 2006). Booth (2015, p. 15) defines “media play” as “activities that articulate a connection between their own creativity and mainstream media, all the while working within the boundaries of the media text.” Toys involving familiar characters, such as those from Star Wars, are offered to players for audience narrativization (Gray, 2010). In other words, even though the characters have known backstories, open-ended, and therefore potentially endless, world-play scenarios are allowed to take place.

Sometimes the stories developed during world-playing do not mimic the storylines or personalities of characters in the original texts. There are numerous playful examples of this in Lehtimäki’s toy photography. As the photographer explains in his book of professional Star Wars photoplay, “I wanted to create my own little stories […]. Some of the images featured main characters, but always outside of the happenings in the movies” (Lehtimäki, 2016, 7, a translation of the Finnish book text). Lehtimäki, known as “Avanaut” on Instagram, had 17.9k followers as of December 2017. One male respondent (anon.) gives a reason for this: “I enjoy seeing Lego Star Wars photos. The combination of realistic background and toy is interesting.” Players have a desire to re-create as well as to re-play, imagine, and world-play. This presents questions about the mythical quality of the original text, as the world-playing with the Star Wars expanded universe illustrates.

Strategies of toying with Star Wars in socially shared photoplay

As Wolf (2012, p. 2) explains, “an imaginary world can become a large entity which is experienced through various media windows.” Today, adult toy play develops in new directions, is more often socially communicated through new technologies such as social media, and is thus more visible than ever. As platforms for collective play and imagination, social media platforms enable players to engage in social play. Mature toy users actively perform play in physical environments, document it (often with a mobile device) and then share the results in digital playscapes. Photoplay is a largely social (fan-to-fan) form of playing as there is an underlying expectation that the produced images will be shared on social media platforms in order to receive feedback from peers. Manifestations of toy play, such as photoplay, provide opportunities to investigate adult toy play. Furthermore, circulated images become invitations for other world-players to participate in dialogues and further photoplay. For example, “The official home of Star Wars on Instagram” had 2,771 posts and 8.5m followers as of December 2017. The nature of contemporary toy play is not only present in play patterns regarding the material dimensions of world-building but also is increasingly hybrid and social in nature (Heljakka, 2016). Furthermore, it has an increasingly transmedial quality; sometimes, it is hard for even for a fan of Star Wars to distinguish between photoplay and original footage:

I looked for a long time at the images on the wall and thought, what is the point to have screenshots made out of actual movie scenes [in the name of art]. And then suddenly, I noticed that these were photographs of toys that looked very realistic. (Interviewee, anon. at Hothcon 2017 Helsinki)

Image 9. Realistic photoplay by Truupperi (Janne Mällinen) showcased at the Hothcon 2017 event in Helsinki.

One male respondent (anon.) says, “[I share my photographs of Star Wars objects] in many different places they can be seen.” Photoplay provides fans the ability to grasp a glimpse of another fan’s toy collection. Thus, the fans interviewed for this study admire other toy collectors’ competencies as curators, displayers, and world-players. Peer recognition of photoplay is communicated through likes and positive comments. Interviewees said, “I love seeing other peoples’ fandom showing,” “Yes, like seeing display cases or scenes made of Star Wars items,” “It’s great to see other’s collections. Sometimes it sparks friendly jealousy.” Friendly competition causes fans to produce more prestigious and innovative photoplay in the future.

Apart from photographs of toy collections, which primarily serve as documentation, world-playing with Star Wars through photoplay is, for the most part, carefully staged and true to the cinematic films. The chosen toy, props, and setting all have an effect on the outcome of photoplay. For example, Lehtimäki’s photoplay aims to replicate the atmosphere of the Star Wars films by mimicking landscape textures in a studio setting. However, he uses familiar characters in unexpected scenes, such as the Stormtrooper on the cover of the book who is humorously engaged in freestyle skiing (see image 7), an activity not featured in the films. On the other hand, toys are sometimes taken outdoors “[f]or nerdy photo-shoots in selected environments” like in the case of Truupperi’s photoplay art (see images 1, 9 , 10 and 11). A male respondent (pseudonym “Fan of Star Wars from Vantaa”) says: “I take photos of my figures in various outdoor surroundings. [I re]create scenes, etc.” Another interviewee explains, “I used to [photograph them], in order to play with them in the garden. Nowadays it has happened a few times that I took a few pictures of miniature starships outside.” Whether in a staged or natural landscape, most Star Wars photoplay aims to combine toys with the “right” environment and light in order to accurately capture the atmosphere of the films. The toys themselves also play a significant role; the different physical affordances of different toys, such as poseability, present world-players with different possibilities.

A wide range of photoplay with Star Wars toys is shared online, such as images of displays, dioramas, and “doll dramas.” The storylines featured in Star Wars-related photoplay address and develop memorable scenes in the films, such as Stormtroopers following Darth Vader in the Death Star, Luke Skywalker gazing into the horizon with RD2D, and active combat situations. Alternatively, photoplay may introduce unexpected content from pop culture, such as accessories from other figures like Johnny Cash’s toy guitar, to familiar characters such as Darth Vader (image 11). Despite its largely visual nature, photoplay is often accompanied by some sort of caption explaining what is depicted or providing a commentary on the motivation to photoplay a certain scene, which invites playful dialogue following the posts. The photoplay shows that fans want to not only cherish classic scenes but also use their creative skills to constantly re-imagine the characters and world-play, often with subversive mash-ups between Star Wars and other franchises. As Harvey notes, the freedom to play with subversive elements amongst professional practitioners and fan creators is actually actively encouraged, as for example the Lego Star Wars range exemplifies (Harvey, 2015, 156). Consequently, the key strategies of photoplaying with Star Wars toys involve artistry (accurate re-playing of scenes or creation of new scenes with an “authentic” atmosphere) or humor (re-imagining of Star Wars characters in humorous situations outside of the original story world, as in image 1, in which Stormtroopers are taking selfies).

Image 10. A mosaic, “#august2017favetoyfotos.” Image 11. Darth Vader playing a toy version of Johnny Cash’s guitar. Both are forms of world-play through photoplay by Truupperi (Janne Mällinen).

Conclusion

As one respondent says, “Star Wars is more than the movies. It is a universe of possibilities that can leave you making your own stories.” In the 21st century, toy play is profoundly visual in nature as well as physical, digital, and narrative. In line with Gray’s idea that popular meanings are developed by audiences, during adult world-play, the plaything as a paratext may come to be associated with stories that were not necessarily present in the original text. In these instances, the desire to play out personally developed plots resulting from object play practices and imagination, not mimicry (Hills, 2010), serves as motivation to create play scenarios. Adult world-play with toys entails complex interactions with fictional and actual worlds and toy characters as well as human networks on social media and in physical playscapes.

On the one hand, in adult world-play activities, the act of building characters and developing their personalities is of major importance, regardless of their original backstories. They are at the center of narrative practices, which may be employed as a partial extension of the transmedially tied and toy company-provided media texts relating to story worlds. Adult world-play with toys may be analyzed by investigating the spatial nature of adult world-play and asking how it relates to physical space, whether in a display or diorama (in an intimate living space), an urban or natural environment, a location relating to a canon text, a site of toy tourism, or an anonymous public space.

As illustrated in the essay, object play practices demonstrate mental predispositions towards and actions with toys, including imaginative and fantastic world-play, and physical or manipulative actions with toys, such as physical world-play. The nature of adult world-play may be explored through the fantastic and imagined terrains of world building and actual, physical locations, either anonymous or canonical, in which world-play temporarily resides and is documented in photoplay or videography. In some cases, a single episodic instance of photoplay is all it takes to provide the player(s) re-entry to a world that once existed in the physical realm but now exists only in the image and the imagined.

In this essay, I have explored how storytelling in relation to imaginative, physical, and hybrid world-play with character toys happens both in the imagination of the adult player as well as in a multitude of play environments. Multimodal communication with a character toy is key when forming a relationship with it and later, when continuing to build its story world. The role of the toy thus develops from personal “eye candy” to a multifaceted and socially shared medium. The toy functions simultaneously as a conversational object and, together with props, backdrops, plots, and documentation, forms a device for storytelling.

Individually imagined worlds of toys become tangible through world-making. During photoplay and sharing of documentation on social media platforms, intra-personal toy play becomes socially shared interplay among many toy enthusiasts. The narratives developed during adult toy play may be based in backstories that originate in transmedia storytelling but may also exemplify toy personalities and plots developed by players. Once photoplayed and posted online, these stories become common ground for the shared imaginations of human players, juxtaposing the physicality of the toy and its built environment with the fictional. What happens to the toy and its personality develop in accordance with world-playing activities, and a hyperdiegetic universe is built for a toy character with the introduction of new events and addition of other toy characters to the story.

According to Wolf (2012), imaginary worlds are often transnarrative, transmedial, and transauthorial. In light of the ideas presented in this essay, it is possible to see how imaginary world-play scenarios including toys are “transtoyetic” in nature, meaning that during toy play, adults, like children, are liberal and creative in their use of mash-ups. Toys of different origins, manufacturers, and story worlds may be used in the same play scenarios, or multiple types of toys may be staged in imaginary worlds that draw mimetically on plots from widely recognized narratives such as Star Wars. There is both new hope and long-term commitment from fans as world-builders to photoplay with the Expanded Universe, as the saga continues with the guidance of Disney. As one male respondent (anon.) says, “This is [a] fandom, which will last till the day I take my last breath.” Another one declares:

It is Americana in its truest form; the greatest thing USA has contributed to the history of art in their entire history. It is global, it is a generational sharing point from young to old and it is a perfect machine for quality entertainment with something to say about love, life and freedom. (Male respondent, anon. b. 1992).

The force seems to be with the toys. Playing with Star Wars’ world continues…

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express her gratitude to the reviewers of this essay, all the interviewees and the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong National Museum of Play for kindly assisting in finding materials on Star Wars toys and films.

Bibliography

Interview with Dean Clayton, owner of the HeadHunter Store, Helsinki, December 27, 2017.

Online survey with 40 Star Wars fans as respondents conducted in December 2017.

DINGILIAN, B. (1977), “Production notes”, in Production Information Guide “Star Wars” [press kit], Beverly Hills, Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation.

FISKE, j. (1992), “The cultural economy of fandom”, in Lisa A. Lewis (ed.), The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media, London, Routledge, p. 30-49.

GERAGHTY, L. (2006), “Aging toys and players: Fan identity and cultural capital”, in Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and John Shelton Lawrence (eds.), Finding the Force of the Franchise. Fans, Merchandise, & Critics, New York, Peter Lang, p. 209-223.

______(2014), Cult collectors. Nostalgia, fandom and collecting popular culture, Routledge.

Godwin, V. (2015), “Mimetic fandom and one-sixth-scale action figures”, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 20, 2015. <http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2015.0689>

Gray, J. (2010), Show Sold Separately. Promos, Spoilers and Other Paratexts, New York, New York University Press.

HARVEY, C.B. (2015), Fantastic Transmedia. Narrative, play and memory across science fiction and fantasy storyworlds, Palgrave Macmillan.

HILLS, M. (2002), Fan Cultures, London, Routledge.

______(2009), “Interview with Dr. Matt Hills,” Part 2,

<http://doctorwhotoys.net/matthills.htm. >

______(2010),”As Seen on Screen? Mimetic SF Fandom and the Crafting of Replica(nt)s”, <http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/imr/2010/09/10/seen-screen-mimetic-sf-fandom-crafting-replicants>

HELJAKKA, K. (2012), “Aren’t You a Doll! Toying with avatars in digital playgrounds”, Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, No. 2, vol. 4, p. 153–170.

______(2013), Principles of Play(fulness) in Contemporary Toy Cultures. From Wow to Flow to Glow, Doctoral dissertation, Helsinki: Aalto University.

HELJAKKA, K., HARVIAINEN, J.T., & SUOMINEN, J. (2017), “Stigma Avoidance through Visual Contextualization: Adult Toy Play on Photo-Sharing Social Media”, New Media & Society, OnlineFirst, 2017.

HELJAKKA, K. (2016), “Strategies of Social Screen Players across the Ecosystem of Play: Toys, games and hybrid social play in technologically mediated playscapes”, Wider Screen No. 1-2, 2016. <http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/2016-1-2/strategies-social-screen-players-across-ecosystem-play-toys-games-hybrid-social-play-technologically-mediated-playscapes/>

______(2017), “Toy Fandom, Adulthood, and the Ludic Age. Creative Material Culture as Play”, in Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington (eds.) Fandom. Identities and communities in a mediated world. Second edition, New York University Press, p. 91-105.

______(2015), “Toys as tools for skill-building and creativity in adult life’, Seminar.net. International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, No. 2, vol., 11, <http://seminar.net/images/stories/vol11-issue2/5_Katriina_Heljakka.pdf>

HENRICKS, T. (2008), “The nature of play”, American Journal of Play, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 157-180.

HORSLEY, J. C. (2006), “Growing up in a galaxy far, far away”, in Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and John Shelton Lawrence (eds.), Finding the Force of the Franchise. Fans, Merchandise, & Critics, New York, Peter Lang, p. 187-189.

JENKINS, H. (2010), “He-Man and the masters of transmedia”, <http://henryjenkins.org/2010/05/he-man_and_the_masters_of_tran.html>

MILLER, D. (2008), The Comfort of Things, Cambridge, Polity Press.

LEHTIMÄKI, V. (2016), Pieniä hetkiä suuresta galaksista [orig. Star Wars®: Small Scenes from a Big Galaxy], Sanoma Media Finland Ltd.

PANTON, J. (2006), “Two generations of boys and their Star Wars toys”, in Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and John Shelton Lawrence (eds.), Finding the Force of the Franchise. Fans, Merchandise, & Critics, New York, Peter Lang, p. 191–207.

REHAK, B. (2013), “Materializing monsters: Aurora models, garage kits and the object practices of horror fandom”, Journal of Fandom Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 27-45.

SAMUTINA, N. (2016), “Fan fiction as world-building: transformative reception in crossover writing”, Continuum Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, vol. 30, no. 4, p. 433-450.<http://www.hanover.edu/philos/film/vol_02/planting.htm>

SCHOLZ, T. (2017), Uberworked and Underpaid: How Workers Are Disrupting the Digital Economy, John Wiley & Sons.

WOLF, M. P. (2012), Building Imaginary Worlds. The Theory and History of Subcreation, New York and London, Routledge.

Wookiepedia, <http://starwars.wikia.com/wiki/Main_Page>

Media

The Force of Three Generations (2011).

The Toys that Made Us, Original Netflix series (2017).

Katriina Heljakka, a toy researcher, holds a post-doctoral position at the University of Turku and studies toys and the cultures of play. Her current research interests include toy fandoms, the emerging “toyification” of contemporary culture, character toys, and the hybrid and social dimensions of transgenerational ludic practices. Contact: katriina.heljakka@utu.fi

Notes

[1] For the invention of the term ‘world-players’, I am indebted to media scholar Richard McCulloch, who suggested that I draw a parallel between this notion and the established notions of world-builders and world-building.

[2] See http://www.gamesradar.com/star-wars-gifts/, accessed January 31st, 2017.

[3] At an industry event, I was able to ask the head of Lucas Licensing about the company’s stance on adult players. This quote from The Force of Three Generations (2011) was originally presented in my doctoral dissertation. See Heljakka, 2013, p. 230.

[4] The industries of play (Heljakka, 2013) are the traditional toy industry and game industry, which were separated but are now merging as toy companies are growing into publishing houses and production companies aiming at omnichannel distribution of their toy-related content.

[5] It is needed to distinguish this definition of the term from a previous one. Photoplay, as a term, was introduced in Hugo Münsterberg’s 1916 book The Photoplay: A Psychological Study and is associated with cinematic films and the magazine Photoplay. These facts were unknown to me when I started to use the term.