AMEDEO D’ADAMO

Universita Cattolica, Milan

Abstract

How is the evil of the Evil Empire of the Star Wars universe constructed and codified in its spaces? In SW space is binary : the spatial cues of Deathstarchitecture – its slick surfaces, rational codes, restricted color palates, alienated unscarred unmarked surfaces, corporate culture and lack of any bathrooms or amenities – oppose it to the good Rebellion which is marked by aged, rough and marked surfaces and a deeply-inscribed sense of historical place, ornament and habitation. Here the spatial theories of non-place (Augé : 1995, 2002, 2004) and of the Third Space (Oldenburg : 1989, 1999) help us see both how spatial codes in the Star Wars universe manufactures its concepts of good and evil, and also how its spaces – and therefore its sense of ‘palpable evil’ – changes over decades. Certain spatial differences between the 1977 Death Star of A New Hope and 2015’s StarKiller Base in The Last Jedi reveal that by wordlessly expressing the audience’s actual, unevenly-shared and historically-determined social and spatial background, space in a fictional universe can be less stable than a canon that is more overtly fixed in the dialogue and actions of characters. This spatial slippage can also help unveil profound shifts and social disjunction in its audiences.

Keywords : Star Wars, Whiteness, Death Star, Non-Place, Third Space Theory, Augé

******

Fig. 1 : The Death Star, iconic emblem of Empire and alienation.

Introduction[1]

There is perhaps no greater signifier of evil in popular culture today than the Evil Empire of the Star Wars franchise. This universe’s ‘evil empire’ has been invoked to describe groups as different as the Soviet Union and the Trump Administration, a wide range which illustrates how this concept of evil paradoxically both divides everything into sharp Manichean categories yet is itself somewhat inchoate, protean and hard to define.

What constitutes this paradoxical melding of obviousness and obscurity? Sometimes evil is easy to understand. For example, most of SW’s tropes are overt: most characters who walk into frame are soon obviously characterized as good or evil by their dialogue, costumes, affect and moral actions and an envelope of music cues. However, this universe’s evil is not only conveyed through avowed allegiance or opposition to the Dark Side and its latest unbridled totalitarian personality. Good and evil are also conveyed spatially, via the Empire’s and the Rebellion’s opposed spatial constructions and styles, which convey meaning not overtly via dialogue, action and costumes but rather through more complex design and architectural connotations, the meaning of which are grounded uneasily in the cultural and historical backgrounds of the filmmakers and audience.[2]

This leads to the question: how is evil itself defined spatially in this universe, and is it done in a fixed, canonized way? In this essay we argue that the apparent “objective reality” of the evil and good spaces of this universe means that the standardized styles of spatial meaning-making in the canon are actually a bit more unsteady than its other machineries of canonization. On the one hand, “style, while remaining hidden, is what makes everything intelligible” (Dreyfus, 2005: p. 5); the style of these evil and good spaces quietly, decisively and yet non-verbally informs us viewers about the Empire and the Rebellion. But because it is not overtly stated in dialogue or narrative events, this spatial codification is more underdetermined and plastic than other forms of more overt canonization: it travels a bit ‘under the radar’ of fans who enforce canon by vocally objecting to more obvious changes. Unmoored from specific lines of dialogue or referenced entries on Wookipedia, the answer to the question of whether the Death Star features high key lighting is less clear and fixed than the question of whether Leia is the daughter of Darth Vader.

This cognitive slippage gives birth to a kind of Spatial slippage in turn: these Empire spaces and styles can subtly shift in the films over time, drawing on different spatial embodiments of wrongness drawn from our own shifting world, allowing the wrongness of the Empire itself to shift and change throughout the canon. And this shift in wrongness in turn redefines the rightness of the Rebellion. In part because of this slippage, the Star Wars universe is a monumental expression of spatial and sensual communication, unfolding across generations, more linked to our own changing world than it might at first appear to its many dedicated viewers. Its own imagined community changes shape just as ours does (Anderson, 1991): in a sense the two are as psychically joined as Rey and Kylo Ren.

But before diving into evil, we should answer a methodological question: why use the term ‘space’ to investigate this phenomenon, as opposed to using older terms such as visuals, design elements or mis-en-scene? I propose three methodological reasons:

First, the concept of Space in narrative theory has traditionally been connected to Kant’s concept of the Time-Space Manifold to help capture the point that any one visual or design element can inflect and help characterize the meaning of any other: a sting of music or a specific echo for example can characterize the meaning of a film’s architecture by bringing out certain of its tropes over others (see D’Adamo, 2018 : Pp. 95-99 for other examples).

Second, I have elsewhere proposed a definition of the narrative concept of space and manifold to show how a scene’s elements form a manifold of meaning.[3] The assertion is simply that viewers learn about Darth Vader’s tendencies and allegiances – that is, we learn how to predict his coming actions in the story – in part because we are informed about Vader through certain spaces like the Death Star, a large corporate environ that is itself lit and framed in a certain way and imbued by a certain score of music and sound design. And when Luke or Han enter this space, that spatial information also informs us how they are in direct tension with it, producing contrasts that inform us in specific and identifiable ways about them as well.

There is also a third reason to use the term space rather than visual or design elements : narrative spaces can be distinct but they can also be contiguous in identifiable ways with our own world. In other words, the term also implies that once we theorists unpack an aesthetic space, we should then try to see how it is contiguous with other spaces, and particularly the ones in which we live. The term ‘space’ captures this attempt to reverse the arrow of implication : after seeing how spaces can be deployed to express tendencies in human agency, we try then to glean information about how the space’s cues might refer back to real spaces in our culture (ie how they reproduce certain spatial and social cues found in our lived world) so that we can better understand how they inform and shape us. And so this is why an analysis of racist and gendered cues in Star Wars then becomes grounds for speculating on the origin of its rich spatial cues in the production of America’s culture, itself informed by the way that certain new American spaces became racialized and gendered in a post-war corporate America.

And so this essay, which begins as an analysis of Star Wars’ spaces, ends as a brief meditation on the historical racialization of space in America. The hope is that a spatialized phenomenological investigation of narrative can also help us grasp the meaning of our own cultural background, which is of course itself a spatialized concept.

We head now into the space of evil: our doorway will be its emblematic monument, the Death Star.

The Monumental Spaces of Star Wars

The Death Star floats large in our collective imagination, an iconic presence as forceful as any produced by the Star Wars franchise, and this massive sphere of specifically mechanical and technical evil introduces a very persuasive form of story space that at the same time defines the entire canon’s other spaces by its oppositions to them. To see this construction more clearly, we must first lay out the building-codes of the Star Wars universe itself.

First of all, most locations in Star Wars’ establishing shots – whether Rebel or Empire, planet or building – possess a massive monumentality, and often one monumentality encloses other vast, awe-inspiring and thus memorable spaces. Consider for example the giant meteor cave in The Empire Strikes Back (1980) that turns out to be the gullet of a huge space-slug, or how Rey in The Force Awakens (2015) is first introduced inside the sublime wreck of an Imperial Star Destroyer. The Death Star exterior as seen from space is no exception : it is theatrically spectacular, a grand eye-opening gesture of the Empire’s power, itself marked by a massive trench that repeatedly invites spectacular Rebel bombing-runs.

However the interiors of the Death Star, which return repeatedly and are on-screen for far longer stretches, present a very different phenomenon. These spaces seem designed to slide away from our glance and memory, conveying less direct but more subtle dramatic spatial meanings even as they frame and enclose our main characters.

The Architecture of Evil : defining canonical Empire Style

Death Star interiors, whether from A New Hope (1977), The Return Of The Jedi (1983) or Rogue One (2016), are an expression of a codified, overall evil Empire building style that extends out across myriad Star Cruisers, Star Destroyers and other grand Empire structures and also includes the Star Killer Base of The Force Awakens (2015), creating an overall architectural connotation of evil. Empire style marries a kind of early modernism to the fascist concept of architecture : unlike buildings that embody a certain humanist-era sense of scale, the Empire’s doors, windows and archways are oppressively enlarged and its surfaces usually feature thick metal sheeting and other tropes of military invincibility where a rigorous industrial functionality bereft of ornament is joined to a scale that is purposefully swollen in order to dwarf and intimidate the individual.

Perhaps its most obvious unifying motif is a distinctive pattern of recessed pill-shaped light-panels in which thick flat metallic cladding is punched by long light-slats with rounded ends (see fig. 8). Another vernacular element appearing across many Empire spaces are the controls operating the firing of large powerful weapons: these square extruded lit buttons are a retro technology native to NASA’s Moonshot era which then descend through Lucas’s oeuvre from the control panels of oppressive technology in his film THX 1138 (1971). Though we find a flatter version of them on the Star Destroyer in TFA, the Star Killer Base itself has advanced to seamless control panels operated by touchscreens, one of its many advances over Death Star tech. However, even these newer controls, built 30 years later in the SW timeline, are often accompanied by 1980s Atari-era white-on-black projected graphic geometrics of war planning (TFA and RO), yet another sign of how the dated tech vision of A New Hope’s 1977 era then became uneasily codified in the Star Wars universe.

Rebel Space vs Empire Space :

How the interior architecture of the Death Star defines the Rebellion

There is of course a clear contrast to the Empire’s oppressive soundscapes and uniform clean, modernist-fascist style: the Rebellion’s spaces. Vibrant and chaotic, Rebel space is a mirror of Empire style: it is authentic, multicultural, communal, lived-in, unstandardized and largely unrationalized, and largely built to human scale (as are its tech spaces). None of the spatial cues of Empire space – its slick surfaces, rational codes, restricted color palates, alienated unscarred unmarked surfaces and modernist designs – are found in Rebel zones : the non-evil Rebellion is marked by aged, lived-in, rough and marked surfaces, a deeply-inscribed sense of historical place, ornament, habitation and a marked horizontality of social functions, all opposite traits from the Empire’s preferred placeless, ahistorical, hierarchical, globalized Modernism. Furthermore, its buildings all have a multiplicity of histories, carry the traces of generations, have women in positions of power, and offer exciting social spaces, unregulated Casbah-like zones and dive-bars where social classes mix, interact and relax.[4]

The good spaces of the Rebellion are alive in all the ways the evil Empire’s space is dead. We can see these Manichean distinctions in three examples.

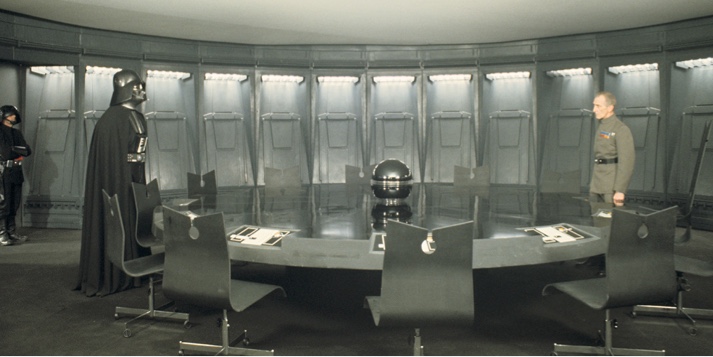

First consider the conference room of the Death Star (Fig. 2, next page). Here we find a tightly-controlled color-pallet, a clean patina of surfaces and a rigid rational organization of the space, all done to convey a sense of wealth, control, prestige, and organized decision-making. Like any powerful corporation’s boardroom, its looming ceiling and the rigid physical affect and the ironed, unstained costumes of the Empire’s ruling class are all designed to project institutional power.

Fig 2. The conference room on the Death Star.

Fig 2. The conference room on the Death Star.

Fig. 3 : a sink from season 3 episode 17:

Fig. 3 : a sink from season 3 episode 17:

Star Wars Rebels « Through Imperial Eyes ».

A sink inside an Empire starship (see Fig. 3) in the canon tv show Star Wars Rebels (Disney, 2014 – ) shows how this canon show is spatially-contiguous with the Death Star. Reflecting a sterility and unfitness for human use, the sink’s sharp edges (rather thoughtlessly dangerous in the slippery realm of a bathroom), its boxy volumes that too obviously reveal their origin in being stamped-out on a factory assembly-line, and the lack of personally-selected toiletries which convey a lack of any markers of personal history, all reflect alienation, regimentation of design, and an evinced unconcern for the comfort of its plebeian users.

Fig. 4. The cockpit of the Millennium Falcon.

Fig. 4. The cockpit of the Millennium Falcon.

The appeal of the Millennial Falcon’s idiosyncratically-cobbled-together, grimy interiors (see Fig. 4) contrasts with the Empire’s austere, rigidly-run zones. Heavily marked by mottled, beaten surfaces, this space is a clear example of the highly-influential “used future” look of Star Wars: note in particular how this set is equipped with actual ejector seats and dressed with other elements of used airplane scrap, all carefully cobbled together by set designer Roger Christian. Note too how the cluttered volume and myriad surfaces, in which nearly every panel is individually differentiated, conveys both the personal history and the precarity of Han and Chewbacka. In this smugglers’ spaceship, itself a space of lawlessness, all the once-rationalized spaces have long-ago been adapted by and layered with a personalized, lived history of hasty, cheap and visually non-rational repairs. Note also its complementary in the casual non-military affect and the wrinkled, stained costumes of the rebels.

Because these two kinds of spaces exist opposite each other, each space’s tropes exist in a hauntological way by their erasure in the other’s: that is, the dehumanizing spaces of the Empire’s board room and boxy sink also spatially reflect the contrasting humanist values of the Rebellion.

Deathstarchitecture : the non-place destined to be blown up

Within this overall logic of Empire and Resistance, there are some crucial distinctions that specifically define the Death Star’s spaces as a particular subset of Empire design that we will call Deathstarchitecture. We use the portmanteau Deathstarchitecture to import the more derogatory insights made about the phenomenon of Starchitecture, particularly its tendencies towards branding an entire community and its insidious potential as described by Hal Foster to eliminate both individuality and social purpose (Foster, 2002 : p. 40). In Foster’s view Starchitecture buildings announced a placeless, rootless architecture with no relation to its surroundings and no commitment to social purpose, spectacles where the individual is not granted a social commons or a space of democracy but is instead intentionally turned into a tourist who can only powerlessly admire the structure’s dominating monumentalism. Furthermore, critics argue that these buildings do not produce social capital but rather devour it by valorizing only a handful of “star” talents in the public imagination, thus limiting the social sense of creativity by proposing a very steep hierarchy that hegemonically grants creative roles solely to a handful of the highest professionals.

We should note though that our term Deathstarchitecture includes not just the architecture but the entire spatial environment of the characters, which integrates dominant aesthetic ideas from the overall space into tiny details of costume, props and surface patina, themselves inflected by Sound Design and Cinematography in many craft elements such as echo and reflectance, all of which create a sensual envelope that gives phenomenological reality to these imagined spaces.

Deathstarchitecture defined

So what are the codified tropes of Deathstarchitecture as distinct from Empire style? In its most tangible aspect, Deathstarchitecture is composed of infrastructural zones of industrial purpose, and specifically dark and off-white rationalized spaces that seem built only to usher troops from one air-shaft to another. Twisting and highly segmented by fiercely-plunging guillotine-like hatches, these corridors offer restricted sight-lines that occasionally open onto larger spaces that remind us of nuclear power control-rooms and futuristic metro-stations. Like an aircraft carrier, the Death Star does not itself exhibit any ornamentation or decoration that celebrates power or embody prestige, but this just obscures its real architectural rhetoric. Such state-sponsored and seemingly-utilitarian engineering projects are actually built as emblems of the awesome: it is their very gargantuan size and monumental purpose itself that celebrates the State that built them.

In all of these ways, Deathstarchitecture carries echoes of various actual spheres, work-zones and architectural intentions in our actual world. And yet it is striking how little design effort has gone into making the Death Star humanly functional in any realistic sense. For example, though the agents of the Rebellion have repeatedly crisscrossed this highly-populated landscape, they have never once burst into a cafeteria or even passed a bathroom. Deathstarchitecture also never caters to human pleasures: it offers no social amenities for its thousands of troops and technicians, no water-fountains or waiting areas, no shops nor bars nor restaurants, no leisure-quarters or gyms or recreational centers, no barracks and no schools. And despite its sizable staffing the Death Star does not feature living quarters or habitation of any discernible kind. How could such a monumental death-dealing platform travel the universe without its staff suffering from extreme depression, sleeplessness and starvation?

Complementing this joyless erasure of humanizing infrastructure are its additional tropes of inhumanity : there are no children on the Death Star and no women. And emphasizing its human male monoculture (and in marked contrast to other social spaces in the Star Wars universe) it hosts almost no aliens and is entirely run by white males. Furthermore, most of the stormtroopers who tromp in military time through its corridors actually lack faces : most remain encased in their white trooper suits.

Once we begin to grasp the oddly-stripped architecture, oppressively gendered and racialized inhabitation of this form of space, we see that Deathstarchitecture is not simply some modernist dungeon, another in a long line of generic Science Fiction totalitarian antagonists. Instead, it seems intentionally one-dimensional, crafted to be a rather pure example of what Marc Augé calls the Ideo-logic – IE, an inner logic of representation that the Star Wars universe uses to explain itself to itself. Most strikingly, Deathstarchitecture is actually a planet-sized elaboration of that form of space that Augé calls Non-place, the zone of malls, elevators and maintenance corridors (Augé, 2002).

Five parallels in particular with Augé’s concept of Non-place jump out at us.

First, both the surface of the Death Star and many of the more complex inner spaces are encrusted with an excess of obscurely-purposive detail: its exterior is highly complexified while its interiors abound with pipes, shafts and small control panels though not one announces itself as specifically demanding our notice. The effect is akin to what Augé calls the excess of information we find when wandering through a supermarket: this unspecific plethora denies any locatable attention and so our focus begins to skate over it all without finding an anchor.

Second, there is a complementary spatial over-abundance, achieved by its continually-emphasized sheer size and maze-like complexity, that blurs our orientation. This is achieved not only when its ghostly 3-D schematics are projected in rebel councils but also as the Tie-fighters skim through the overabundant blur of extruded buildings, factories and machinery on the Death Star’s surface.

Third, there is a problem of orientation in its interiors, which twist and turn to block our sight-lines and provide no overall anchoring windows, signs or unifying elements that might help us relate each space to others or to place them spatially within the overall structure.

Fourth, all of the design looks standardized: built of easily-fabricated, swappable materials, and unlike the “used future” feel of walls and materials in the rest of this universe, these places carry no marks or patina of human passage, inhabitance or tinkering and exist instead in the endless formal present of corporate lobbies and consumer showcase spaces. This trope of rootlessness seems to spring from Modernist architecture and design which celebrated clean lines and aseptic surfaces instead of using organic materials: instead of showing the accretions of life on a surface as older building materials did, these same easily-replaceable industrial components and materials carry no marks of use and so feel phenomenologically ahistorical.

Fifth, Deathstarchitecture also blurs in memory because most of its settings are instrumental places. Spaces on the Death Star that we glimpse in the distance or on schematic diagrams seem indistinguishable from the immediate setting not only visually but also in terms of their purpose. The phenomenology of infrastructural zones only further undercuts our sense of belonging because in real life we usually pass through such infrastructural zones on our way to get somewhere else. In this way this endless infrastructure of corridors and air-shafts fits Augé’s definition of Non-place.

The result of all of these design-choices is a notably-pronounced anonymity of place : if we try to recall any particular place in the Death Star we often find them all hard to remember with any specificity. Aside from the funky trash compactor that is emblazoned in memory by its jumbled trash and a singular eruption of peculiar life, the realm of Deathstarchitecture is an unusually blurred space offering our memory little geographic detail, logic, anchored concreteness or orientation: instead it exhibits what Augé calls the oblivion and aberration of memory that we experience in our blurred memories of giant, generic hotels that lack all personal marks or décor and so lack their own deep architectural identities.

For all of these reasons it is perhaps not surprising that the rebel intruders always need the help of androids to map, navigate or make sense of the Death Star. Their confusion is of course further emphasized by a total lack of signage which would be particularly helpful for its lowly native stormtroopers. This weird absence is not specific to Deathstarchitecture: rebel cities also largely lack street signs, business marquees, price-lists or billboards, reflecting a universe-wide resistance in the Star Wars universe not only to signage but to typography in general (perhaps even to literacy itself). Yet despite this, most non-Empire spaces have a unique and anchored quality: unlike Deathstarchitecture, we know when a place is new to us and when we have returned to somewhere we have been before.

Moreover, when lensed through another elaboration of space, that of the Third Space theory of Ray Oldenburg (1989, 1999), yet another level of the designed alienation of Deathstarchitecture comes sharply into view. Third Space theory argues that most spaces in contemporary life fall into Work Spaces, Home Spaces, and then all the common public spaces that make up the Third Space, and further that the balance between these three forms of place informs us about how democratic and caring a culture is. Cultures that grant a flourishing life usually offer a balance of the three distinct realms of home life, the workplace, and inclusive sociable places.

Third Spaces are almost always observed in the spaceships hosting space operas : think for example of the chess-playing couch on the Millennium Falcon. Similarly, while the canonical USS Enterprise in Star Trek may resemble a giant office-building flying through space and has none of the personalized, taped-together “used future” charm of a Millennial Falcon, a Nostromo (Alien, 1980), a Serenity (Firefly, 2005) or even of the Gallactica (Battlestar Galactica, 2004-09), the canon Enterprise nevertheless has distinct Home spaces: its living quarters usually featuring items of personalization that reveal the history and character of the inhabitant. It also features Third Place common zones like the bar and the cafeteria where people are ‘at ease’ in both the military and the physical sense, spaces where power is more diffused and people are more likely to flirt, joke and speak their minds. By contrast, the Death Star has neither Home spaces nor Third spaces : it offers only a uniform Work Space that mixes corporate and military tropes rather like some endless Kafka-esque office building maintenance sector.

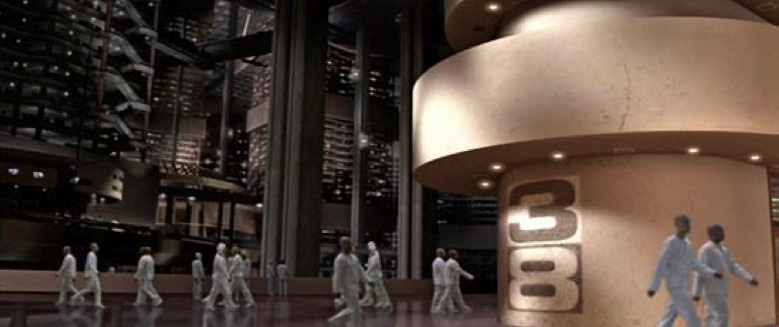

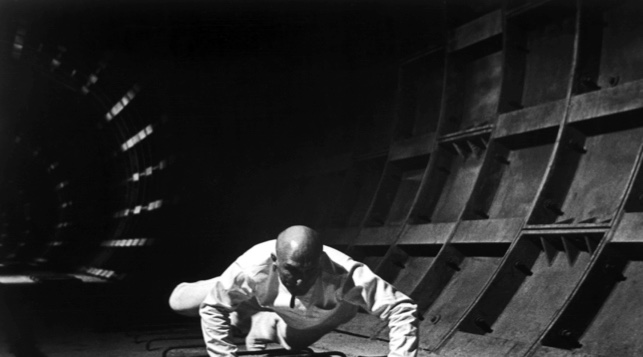

All of these techniques for characterizing evil were used earlier by Lucas himself in his 1971 film THX 1138 (see figures 5 thru 9 below), so much so that that film’s dystopic spaces can be considered a kind of prototypical Deathstarchitecture. The only sign of difference is a kind of encrusted infrastructure: in Deathstarchitecture the sterile clean lines of THX 1138‘s white halls and infrastructural spaces have become overlain by an elaborate extrusion of technical and physical infrastructure that have assumed but opaque purpose.

Fig. 5 : the hallways of THX 1138.

Fig. 5 : the hallways of THX 1138.

Fig. 6 : THX 1138

Fig. 6 : THX 1138

Fig. 7 : Like the Death Star, THX 1138 features all-white figures and walls.

Fig. 7 : Like the Death Star, THX 1138 features all-white figures and walls.

Fig. 8 : the Proto-Deathstarchitecture of THX 1138 : here too human figures

Fig. 8 : the Proto-Deathstarchitecture of THX 1138 : here too human figures

dwarfed by Fascist architecture march in white uniforms.

Fig. 9 : THX 1138: space grows more gritty and unrepaired as

Fig. 9 : THX 1138: space grows more gritty and unrepaired as

the protagonist flees towards the freedom of the surface.

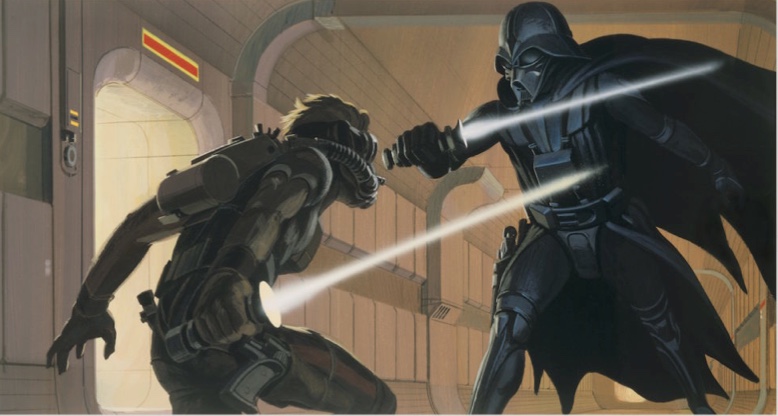

As Lucas developed the world of Star Wars, THX 1138’s aesthetic of spatial infrastructure was filtered through the vision of the Star Wars previsualizer/designer Ralph McQuarrie, who himself had illustrated for NASA and for Boeing Industries before meeting Lucas in 1975. As figures 10 through 12 show, McQuarrie brought both a new sleekness of line and an extrusion of infrastructural detail to his spaces, thus refining both Empire Style and Deathstarchitecture.

Figs. 10 & 11 : The Death Star interior

as envisioned by Steve McQuarrie

Fig. 12 : the Death Star interior realized.

Fig. 12 : the Death Star interior realized.

However, it was the transformative Star Wars set dresser Roger Christian who added the many gritty and worn elements of a “used future” (see fig. 12) that so profoundly differentiates the opposing Rebel Space from McQuarrie’s Deathstarchitecture and Empire style. Almost nothing in the Empire’s spaces display the “Used Future” look that defines both Rebel zones and the many struggling economies across this galaxy, and many meanings come tumbling out from this choice. Consider only the socio-economic impact: unlike the Empire which controls a giant military-industrial complex, a massive war machine that can produce and crisply maintain these fresh-minted armaments, the Rebellion’s spaces speak of a fractured, dispersed ragtag underdog that has lost the most developed regions of the galaxy and survives by hiding guerilla-style in poorer regions and forgotten planets. In a real sense designers McQuarrie and Christian each had a real role in defining and sharpening the two opposing sides of the Star Wars canon not only in terms of their aesthetics and their social purpose but also their respective economic and empathetic foundations.

The Dramatic role of canonical Deathstarchitecture

Once we recognize these divisions two questions can be asked: first, why this particular Ideo-logic for Deathstarchitecture? And second, is its phenomenology powerful enough to be called canon or not?

On one level the anonymity of these places plays a specific dramatic role: when the corridors of the Death Star are not being used for gun- and light-saber battles they play as unobtrusive backdrops, their very unspectacularity and generic nature helping to focus our attention on the foregrounded characters while a dramatic argument is taking place (See D’Adamo, 2018 for the uses of dramatic space).

But when we step back to view Deathstarchitecture’s marriage of sterile institution, opaque rational instrumental purpose, corporate maze and pure work space, a larger and more powerful emotional logic to the Death Star becomes obvious.

We long to destroy such places.

And that is why the Death Star’s fiery destruction offers a perfectly-calculated final spectacle : unlike Deathstarchitecture’s own vivid destruction of lived organic worlds (including, it is crucial to note, even non-aligned planets), there is nothing, no-one, no history or social realm, no play space or third space, no joyful spontaneity or subjectivity to empathize with when such a gigantic, corporatized, pure work-space is spectacularly blown up. Good riddance to all that evil alienation.

Alienated Space : a short history of Ahistory

But after this analysis it is worth asking : what evil, exactly, do we audience members feel is being heroically blown up? After all, the Death Star and the dystopia of THX 1138 are not sui generis: to evoke some pre-existing tropes of evil and wrongness in viewers they each must manipulate and utilize existing elements in the social imaginary that are already phenomenologically experienced as ‘wrong.’ So what are these ‘evil’ elements: do these extrusions of Empire style remind us of any spatial wrongnesses in our actual lived universe? Where does Deathstarchitecture come from : can we identify its historical roots?

The first clue that it might lies in the fact that many of its same techniques can be found in other, radically-different films made at the same time by quite different filmmakers. Consider One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, an American drama from 1975, the year that Star Wars itself was being fashioned by Lucas. Made from a famous countercultural novel and directed by Milos Forman, the film features an anarchic, quick-talking trickster charismatic figure who leads a rebellion in a psychiatric asylum (see fig. 13). The same story oppositions of DeathStarchitecture exist in this film’s space: it too aligns the oppositions of Repressive Authority vs. Free Individuals, Organized vs Chaotic, Institutional White vs. Color, Clean vs. Dirty, Ironed uniforms vs Rumpled clothes, Precise speech vs. Casual speech, etc.

Fig. 13 : One Flew over The Cuckoo’s Nest.

Fig. 13 : One Flew over The Cuckoo’s Nest.

Arguably this spatial parallel of oppositions is no coincidence. First of all, in the 1940s some of these distinctions began as standard oppositions that the Allies of Europe and America used to define themselves first in opposition to the Nazis and then in the Cold War to the institutionally-constructed totalitarian culture of the Soviet sphere. But they also have another origin.

The same elements also map onto the radical re-spatialization of America that took place between the 1940s and ’70s when Lucas was coming of age. These decades saw the United States react to both the war and the subsequent Soviet threat by moving from a dispersed small-market economy to a federally-planned corporate capitalism, a transformation using new forms of urban and suburban planning that created certain spatial and cultural oppositions. In this massive modernization, the clean sterile aesthetic of the Bauhaus movement with its use of cheap, mass-produced materials combined with the electrification of the country and the massive expansion of roadways and zoning grids, all imposed by a partnership between a massively-expanded federal government and newly-gigantic corporate entities.

All this planning was highly (and yet selectively) effective: by 1976 in America most whites had been elevated out of poverty by the past five decades of the New Deal’s programs to live in the fresh-minted suburbs and work as ‘professionals’ in the new high-rises, corporate office towers and business parks while leaving blacks and other minorities in the poor, run-down and crumbling inner cities. For these whites ordinary life was transformed: these new white-collar and white-culture zones were suddenly defined by gridded borderless suburbs and all-controlling bureaucratic corporate boardrooms and sprawling office parks, creating a rationalized grid that imposed a new sameness as it quickly spread across the country, erasing regional differences and bonded a cold-war white generation in a common experience as it changed the nature of their homes, workplace and cityscape.

But soon a reaction among the white culture itself began: these new spheres became blamed for the alienation of modern life. In the 1960s this anti-modernist critique became engaged with a Marxist and Situationist understanding of the concept of hegemony and the phantasmagorical nature of city space, as well as new critiques from the budding New Left and others of the psychological controls of large institutions and of capitalism (Marcuse, Foucault).

In this broad counter-cultural front of rebellion, alienation was marked by social hierarchy, practiced precision of speech and behavior, uniforms, social scripts, the tropes of militarism, consumerism and of traditional conservative white culture, where social niceties were equated with social control, rule-following and the organized settings of American suburban homes, modernist corporate environments and white hegemony. These tended to be identified with the suburbs and with small-town white America and with government, corporations and white men. By contrast, authenticity was identified with messiness, informality, recycling, nature, cultural and ethnic otherness, marginality and the breaking of borders and other cultural markers. This was a powerful and convincing set of divisions but, though these categories appear in counter-cultural narratives like THX 1138, Star Wars: ANH, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s, one aspect is often left unspoken and lies latent in their phenomenology.

A racist knife had been used to carve these new spheres.

The same New Deal programs that had raised up the white population and caused these alienations had also purposefully excluded black Americans from home-owner loans. While whites headed to suburbs and corporate work, government covenants herded black people into old, neglected, dirty inner-city zones or froze them in rural poverty while institutionalized racism kept them out of the new professional arenas and spaces (Harris, 1993; HannahJones, 2012; D’Adamo, 2017). This racial spatial exclusion then reinforced other stereotypes: in the new white culture blacks were identified as funky, as messy, as out of control and unfit for the Wasp-centric economy, all emblems opposed to the developing cultural concept of Whiteness that clearly incorporated the country’s slavery inheritance as a central undergirding binary. Conservatives would approve, regarding these new boundaries as a sign of safety and rightness, but countercultural whites would assign authenticity to Black binaries, identifying themselves with its tropes and defining conservative position as alienated, inauthentic Whiteness. The corporate boardroom became an arena of sterile clean rationalized lines, a place where decisions were made by suit-clad, pressed, manicured white men (consider the Death Star’s boardroom in fig. 3 above), while the roles for black people in these new white-collar corporate spaces were limited to low-paid unskilled blue-collar work like janitors (think of Finn’s role in sanitation on the Star Killer Base.)

For the most part this latent Whiteness/Blackness binary does not exist in Lucas’s SW universe: while black figures are integrated into the Republic and fight in the Rebellion and are absent from the Empire, no special notice is made of racism before 2015. One small sign of this grand spatial tumult in America is there in A New Hope when the droids are excluded from the Cantina bar by the angry white bartender who shouts that “we don’t serve their kind here!”. In Lucas’s original films, droids stood in as an enslaved underclass while black people apparently lived an integrated life as equals among whites.[1]

How the Starkiller Base of 2015 is not like Deathstarchitecture

This same set of historical divisions present differently in the Death Star of 1976 than they do in 2015 when the strikingly-similar Starkiller Base hove onto the screens more than a generation later. On one hand the alienation tropes grow much muddier, but on the other the underlying racism latent in the actual spatial division becomes more evident.

To see this, let’s first formally restate the spatial alienation techniques and tropes found in Deathstarchitecture.

They include :

- Crafting non-place, a hard-to-remember place of no specificity or anchoring landmark.

- Creating a rigidly rationalistic space of vague but dominant instrumental logic, removing all aspects of present-at-handness so that all is a ready-to-hand tool of technè.

- Staging sets that use surfaces that have little or no mark of time, history, or variation of architectural vernacular.

- Erasing Home Space and the Third Space and making all a contiguous Work Space, thus erasing all marks of homeyness, community, autonomy, play and human flourishing.

All of these tropes of inorganic, inhuman architecture makes Deathstarchitecture a rather pure form of alienated space, a distinct and layered form of spatial wrongness. By contrast, on a design level the SKB is often closer to other more generic Empire interiors. First it is more slick and less retro than Deathstarchitecture, an explicable departure as this story takes place three decades after the Death Star’s design. However, the SKB offers even more radical departures from the older aesthetic. Consider the corridor of the SKB (TFA 1:43:20) which resembles an old WW 2 submarine far more than the canonical Death Star. Even more strikingly, the penultimate grand catwalk confrontation between Han Solo and his son (figures. 13 and 14) is nothing like canon Death Star space : full of negative space and all lit by a grand raking beam of sunlight alà Caravaggio, it is both monumental and conventionally sublime, using a dramatic contrast between the fragile-looking, unsafe handrails and the massive walls and endless hole, all oriented with the external space thanks to the dying sunlight’s beam.

Fig. 14 : The final catwalk battle scene in The Force Awakens.

Fig. 14 : The final catwalk battle scene in The Force Awakens.

Fig. 15 : Ibid.

Fig. 15 : Ibid.

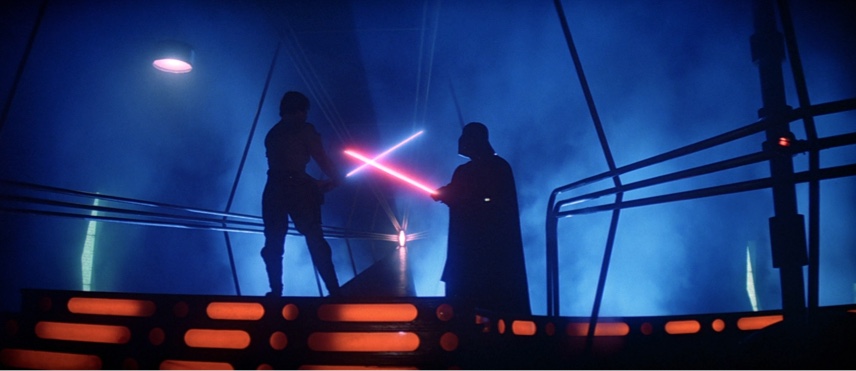

In fact with its small red lights and rising vented steam and its thin causeway extending vertiginously over a great monumental shaft into which Han will plummet, this space is clearly modeled not on the Death Star but instead on the location and elements of Cloud City’s maintenance core in The Empire Strikes Back (figures 15 & 16) where Luke plummets after fighting his father, Darth Vader. Abrams clearly crafts a spatial continuum between the SKB and Cloud City to evoke parallels in the fraught, murderous father-son relationships of these two scenes of betrayal. As a result the SKB’s space is both highly memorable and clearly oriented, quite unlike the purposefully-unmemorable maze of Deathstarchitecture.

Fig. 16 : the final catwalk battle scene in Cloud City’s

Fig. 16 : the final catwalk battle scene in Cloud City’s

infrastructural core in The Empire Strikes Back

Fig. 17 : Ibid.

Fig. 17 : Ibid.

This mix of other location elements, combined with the elements of rock and organic planetness in the SKB corridors (TFA 1:36:30) that remind us we are on a planet and not a battleship, also distinguish the SKB from Deathstarchitecture, anchoring it all instead in the more conventional gothic SF space of general Empire design so dominant in The Last Jedi (2017). In TLJ most Empire style is a generic recycling of genre-tropes, usually a black dungeon-space while Snoke’s throne-room is a glossy red that one reviewer called Argento-like, referencing the famous horror-genre director. Such gothic space is associated more with the magical dark side of the force rather than the more purely technical evil of Deathstarchitecture, thus echoing the spatial tropes of fantasy as opposed to that NASA-like sterile white tech space, the Promethean bed of Science Fiction interiors which Deathstarchitecture references through a prism of alienation.

And then there is the divisions of racism. Although actual racial divisions are largely buried in Lucas’s spatial oppositions and social divisions, the post-Lucas SW universe consciously excavates them to characterize the imagined communities of both the Evil Empire and the Rebellion. Consider how Abrams’ 2015 installment overtly staged a white-power Nazi rally on the Starkiller Base. More strikingly, at one point Finn explains that he was raised by the Empire as a slave with no name: suddenly we realize not only that the SKB itself was probably built through slave labor but that the Empire has grimly institutionalized it for at least a generation: with that admission violent racism and institutionalized slavery become canonized as part of the Empire’s evil. Now actual historical racialized strategies of property and space which map onto a hegemonic, spatial geography of real opportunities and exclusions that are only suggested in Lucas’s Deathstarchitecture become overt and dynamic. 2016’s Rogue One emphasized these new binaries by casting a band of people of color as the protagonists against a particularly-pasty-faced group of white male Empire surrogates. And the real battle-line of this new form of Evil were then outlined in fire when Rogue One’s screenwriter Chris Weitz called the Empire a “white supremacist (human) organization”. This seemingly-innocuous remark triggered a revealing firestorm among Trump supporters who objected to the idea of tarring the fine name of white supremacy and the glowing history of American slavery with the horrible evil of the SW universe. If the original oppositions of Star Wars did not overtly express a broad cultural critique of Whiteness or Deathstarchitecture’s latent historical roots in Italian fascism, these new choices and the reactions they triggered from racist Americans certainly did: this controversy over RO, with its implied celebrations of the old slave south, made Abrams’ SKB Nazi rally seem a prescient revelation of what was fundamentally wrong with not one but two Empires.

And so the ever-present power of Evil in Star Wars has changed since 1977 from a more technical and corporate evil to a more magical evil based on slavery. The Empire’s leadership choices reflect this: compare 1977’s ANH‘s General Tarkin, an SS-like master strategist with no magical powers but who knows how to run a board meeting, take credit for others’ work and climb the ladder of power, to 2017’s TLJ’s Snope, a Supervillain who is a master of the Force and really really big. Supporting and reflecting this change are the different grand stages of these Evil leaders, each carrying quite different spatial references and connotations. All these changes together show how the Empire’s Evil has shifted across the decades from an alienating dehumanizing corporate force into a racist and enslaving force. But should this change in what is evil in the SW universe be understood as a change in canon or as a slow reveal of the tropes of Empire style and a radicalization of the counter-cultural social criticisms implicit in the Rebellion’s aesthetic?

That question highlights how the Manichean simplicity of the Star Wars universe turns it into a device for looking back at our own world more clearly. Consider for example one big difference between the two universes: SW is not a globalized space. It has no cellphones, no social media, no traffic laws (no roads really), no signage and no advertisements (it seems to have no consumerism). This grand imagined space lacks the great harnessing emblem of neoliberalism, that grid that now defines human freedom in our world even as most of its avenues are largely one-way for most of those it touches. By apparently linking all points of the earth this grid marbles all our spaces into one. It binds and blinds us, appearing to create freedom while increasingly becoming itself a great device of surveillance. The erasure of this grid from the SW universe grants two things. First, it gives a clarity of political and moral vision to its real divisions. Second, it grants a far greater sense of refuge in the margins and thus a concomitant sense of the kinds of moral agency we are seeing disappear in our own lifetimes.

And so we might ask ourselves : as racism and slavery grows more visible in SW why does it grow both more obscured and more justified in ours? Why are the very same evils that create a fun engine of conflict in a mythical universe so easy to ignore in our own? Why is the whiteness of our world so hard to make out? Perhaps because the same non-magical evils that are so manicheanly offered in SW’s spaces instead are hegemonically marbled throughout our own, making the history of our own spaces far harder to see.

What is clear is that in both universes as of 2015-16 the evil of Empire has changed and the Resistance grows more diverse. By stripping away its unstated anti-corporate message to focus overtly on the evil of slavery, the franchise has actually reached out into our living politics with a force that has surprised Disney, the corporate entity that now produces the films. Will that fierce outcry by the newly-empowered far right frighten Disney into changing the evil of Empire yet again? Whatever happens next, one hopes that it will be hard for fans to ignore the anti-slavery message of the Rebellion. If that has become overt canon, then the war between the Empire and the Rebellion now spans many new worlds. Including ours.

Bibliography

ANDERSON, B. (1991), Imagined Communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London, Verso Press.

AUGÉ, M. (1995 ), Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London, Verso Press.

_______(2002), In the Metro. Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press.

_______(2004), Oblivion. Minnesota, University of Minnesota.

_______(2016), Everyone Dies Young: Time Without Age. New York, Columbia University Press.

BLAUVELT, C. (2012), “Ralph McQuarrie, ‘Star Wars’ concept artist, dies at 82.” Entertainment Weekly, March 4, 2012, <http://ew.com/article/2012/03/04/ralph-mcquarrie-star-wars-artist-dies/>

BOBO, L. et al. (2012), “The Real Record on Racial Attitudes.” Social Trends In American Life. Edited by Peter Marsden. New Jersey, Princeton University Press.

COHEN, R. & SHERMAN, D. (2016) Theater Brief. New York, Mcgraw-Hill.

CHRISTIAN, R. (2016), Cinema Alchemist: Designing Star Wars and Alien. Titan books, Random House.

D’ADAMO, A. (2017), « That Junky Funky Vibe : Quincy Jones’ title theme for the sitcom Sanford and Son. » In Music In Comedy Television, edited by Liz Giuffre and Philip Hayword. Abingdon-on-Thames, Routledge Press.

_______ (2018), Empathetic Space on Screen : creating powerful places and settings. Cham, Switzerland, Palgrave Macmillan.

DAVIS, M (2006), City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. London, Verso Press.

DREYFUS, H. (2005), Introduction to Time and Death: Heidegger’s Analysis of Finitude by Carol White. Farnham, UK, Ashgate Publishing.

FOSTER, H. (2010), Design and Crime. London, Verso Press.

GATES, H. (1988), The Signifying Monkey. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press.

HANNAH-JONES, N. (2012), Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Civil Rights Law. Kindle Edition. Electronic: Propublica Publishing.

HARRIS, C. (1993), “Whiteness as Property.” in the Harvard Law Review, Vol. 106, #8, Pp. 1707 – 1791.

OLDENBURG, R. (1999), The Great Good Place. New York, Marlowe & Company.

Amedeo D’Adamo currently teaches film directing (narrative & doc) and feature film marketing at Università Cattolica in Milan and Brescia and is the Lead Instructor for the LA-based Native American Feature Film Writers Lab, run by the Barcid foundation. He was the architect and then Scientific Director of the Apulia Film Commission’s E.U.-funded Feature Development Program Puglia Experience (2008 – 2011) and was the founding Dean and then President of the Los Angeles Film School. A filmmaker, his features have been to festivals such as Rome, Miami, Austin, Torino and others. A working script doctor, he also mentors in various programs including the MAIA Film Producing Workshop and ScriptAlba. His published work includes essays on Science Fiction, David Bowie, Gender, Racism and nationalism : his new book Empathetic Space On Screen : Crafting Powerful Place and Setting (Palgrave, 2018) is about how psychological space is expressed in a film’s production design, cinematography, costume and music.

Notes

[1] As one reviewer of this essay has pointed out, the Expanded Universe makes the Empire’s racism and sexism overt in many places : note for example the case of Admiral Thrawn.

[1] This essay is dedicated to the field of architectural theorists who have explored the social ramifications of architecture, in particular the inspiring Hal Foster, Rem Koolhaus, Charles Jencks and Mike Davis, and especially to my friend the architect and theorist Michael Silver.

[2] We might mistake these spaces as “fixed” because the SW universe stays in a kind of objective dramatic space: this universe is never seen “through the eyes” of a character and so never gains a psychological filter that we fans are to understand is subjective (a phenomenon we sometimes experience in the Marvel universe (D’Adamo, 2018)). Instead fans understand that the ‘real’ locations are not psychological spaces but rather look and feel to all the characters roughly as we viewers experience them.

[3] An extended definition as well as numerous examples are provided in D’Adamo 2018, but I offer this short summary. Modifying Cohen and Sherman (2016), I propose that any element in narrative (by itself or in contextual combination with others) can function in any or all of the following six ways: reveal the Past; advance the story in the present, usually by either revealing the objectives of the character(s) or by revealing the obstacles or threats to the character(s); foreshadow the future of the story; reveal character; reveal relationships; entertain or engage the audience, often through spectacle or comedy. In this definition Space is best understood as a Characterological Manifold (where the term character is understood as meaning the tendencies in how a character acts). This definition is both analogous to yet quite distinct from Bakhtin’s concept of the Chronotope as many contemporary theorists now use it when theorizing about narrative space. Here the term Manifold is not used to de-contextualize narrative spaces and delink them from a story’s characters: instead it emphasizes how the panoply of cinematic elements often offer readers and viewers important subtle information about the tendencies, goals, objectives, fears and dreams of the characters found inside them.

[4] In proposing this binary of spaces as a way to understand the Star Wars universe, I am privileging the anarchic and often-counter-cultural origins and spaces of Han, Luke, Ren, Rey, and Finn over the spaces of the New Republic and its characters. I defend this first by pointing out Lucas’s own apparent allegiances to the counterculture, in which law and order are often the vehicles of oppressive power. Second, I find it difficult (and somewhat uninteresting) to define the New Republic’s spatial identity. Consider the unclear identity of even the New Republic’s main emissary among the franchise’s protagonists, Princess Leah. Her origin-story (the daughter of a Republican senator who was then adopted by a queen) combines the usually-opposed concepts of a Republic and a Monarchy, and yet with her foul mouth, spunky style and attraction to Han, even Leah often seems more countercultural than royal. Also, the New Republic’s spaces usually seem quite upper-class and well-ordered while both the Alliance’s and the later Resistance’s ad-hoc military bases and rag-tag teams are more contiguous with the chaotic Neutral zones that neither the Empire nor the Rebels control. Finally, note that each rebellion against the Empire is a quasi-unified front of resistance that includes many groups who often must fight in protean, guerilla-style units. As a result the Neutral Zone’s anarchy, multiplicity, lack of breeding, adventurous offerings and improvisational styles are I think deeper markers of the multi-front, multi-world alliances of the Rebels than the well-bred, well-trimmed quasi-roman tropes of the New Republic’s spaces. In a related note, I here focus on the first trilogy and the three most recent films (as of 2017), ignoring much of the entire second Trilogy, a series whose spaces and divisions somewhat inconsistent and whose narratives are, partly for that reason, less engaging for me. I also ignore much of the rich tapestry of the Expanded universe, but that neglect is due only to the fact that this essay’s length is, like so much else, limited by spatial boundaries.