Tristan Donovan

In this keynote address, I provide an overview of the thinking and methodology that underpinned my 2010 book Replay: The History of Video Games. I start by explaining the flaws that I felt existed in previous video game histories and how that informed the key goals I had in mind when researching and writing the book. I then outline, with examples, the research methodology I used to try and examine trends in the medium’s history. Finally, I conclude with several lessons for game historians that came out of researching and writing Replay.

Keywords

Video game, Game history, Methodology, Europe, Replay: The History of Video Games

*****

I thought I would talk today about my book, Replay: The History of Video Games (Donovan, 2010). Specifically, the ideas and the research processes behind it.

Replay was my attempt at writing a comprehensive, global, narrative history of video games that traces the medium’s evolution from inception to the present, which at that time meant early 2010. It is worth pointing out now that when I use the term ‘video games’ I mean it in the broadest possible sense. My definition includes console games, coin-operated games, computer games, mobile games, social games, and so on.

Replay was my attempt at writing a comprehensive, global, narrative history of video games that traces the medium’s evolution from inception to the present, which at that time meant early 2010. It is worth pointing out now that when I use the term ‘video games’ I mean it in the broadest possible sense. My definition includes console games, coin-operated games, computer games, mobile games, social games, and so on.

The path that led to me to write Replay was journalism. I am not an academic. I dropped history at school around the age of 16 and studied ecology at university, spending my time tramping around soggy moors measuring moss in the rain.

However, by what is, in hindsight, pure luck, I got side tracked and ended up becoming a journalist. Most of my career hasn’t involved writing about games. I’ve spent the bulk of my career reporting for and editing publications covering politics, social work, schools, and other public services.

Writing about games was a freelance sideline that I dipped in and out of, doing the odd feature for Edge, Eurogamer or Gamasutra here, and game reviews for Stuff and The Times of London there. But then, in 2008, two things happened that prompted me to write Replay.

The first was that I lost confidence in my employer, a large British magazine publisher. They had always been slow to embrace the internet. The head of the company once called the internet “white noise”. In 2011. So thinking that I didn’t want to become a journalistic fossil, I decided I needed a side project.

As it happened, I had just read some of the game history books available at the time. I enjoyed them, but these books also left me disappointed at how they approached video game history. For weeks afterwards I kept thinking, ‘I wish someone would write a history of video games that addressed the things that disappointed me’. Eventually I thought, ‘Hang on, I’m a writer and I’ve written about games and I want to do a side project. Why don’t I do it?’.

Now if someone had taken me aside then and told me that writing Replay would swallow up every spare waking moment of my life for the next two years to the point where I had the shakes for a while after finishing it because I had forgotten how to do normal things like sit down and watch TV – I might not have gone through with it. But no one did take me aside and by the time I realized what I had taken on, I had come too far to turn back.

So what were these things that bothered me about how game history was being presented enough to write the book? There were five things in particular.

The first and the most glaring issue for me as a Brit was the lack of attention given to Europe. These histories were almost exclusively histories of video games in the USA, so much so that it seemed like the world map according to games was almost blank. We had the USA and we had Japan or rather the Japanese games that crossed the Pacific and then two tiny dots: Moscow because of Tetris and then this tiny town called Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire, England, the birthplace of the game developer Rare who got a brief mention for making the Super Nintendo game Donkey Kong Country.

It felt like the gaming history of my home country, hell my entire continent, had been erased and replaced by an assumption that everyone was playing Super Mario Bros. on their Nintendo in 1987. But we weren’t. Instead in Europe, we were mostly playing European-made games on home computers. Yet with these video game histories it seemed as if the bulk of the gaming experiences that me and everyone else living within a two-hour flight from Paris didn’t matter.

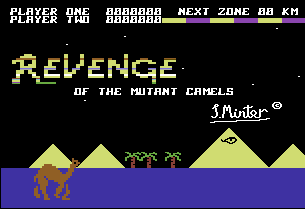

It’s gaming history without the Commodore 64, the biggest selling home computer model of all time, and Revenge of the Mutant Camels, one of many camelid-themed shoot’em ups created by the cult British game designer Jeff Minter.

|

|

| Credit: Christoph Federer |

It’s gaming history without the ZX Spectrum, the low-cost home computer that dominated the British market in the 1980s and was home to best sellers like Jet Set Willy, a Monty Python-infused platform game where you play a multi-millionaire miner who has to clean up the empty bottles from last night’s party in his mansion while avoiding deadly toilets and other strange enemies.

|

And it wasn’t just Europe’s gaming experiences that were missing from these histories. Japan’s domestic games market went ignored as were the video game histories of almost every nation in the rest of the world.

The gap between the computer-focused European and console-focused American gaming histories of the 1980s and early 1990s also highlights another issue I had with the histories I read: console generations. The history of games had somehow become the history of game consoles. It is understandable in some ways. It is a much, much easier story to tell. It’s clean, linear and tidy. But neat and easy a structure as console generations are for a writer, it’s a deeply flawed framework.

One of the problems with it is that console generations are largely a product of marketing. Console wars are great for all involved. The rivalry of manufacturers generates buzz, creates excitement, spurs sales. Sony, Nintendo and Microsoft all benefit from being participants in console wars. It’s like the Cola Wars of the 1980s and 1990s where Pepsi and Coke slugged it out, encouraging consumers to pick a side in a corporate image war where the only real losers were the soda companies that aren’t PepsiCo or Coca-Cola (Donovan, 2013).

Console generation wars are no different. The concept of console generations exists first and foremost to sell units of hardware. The problem is this can distort how we view game history because everything becomes seen through a console generation prism. It encourages us to overvalue the importance of some games because they gave one console manufacturer an edge over its rivals.

Donkey Kong Country on the Super Nintendo is a good example. It gets regular mentions in game histories because it sold loads and gave Nintendo the advantage over Sega for a while. But what did Donkey Kong Country really add to the medium of video games? What did it do to deserve to go down in history as an important game? I’m open to suggestions, but I couldn’t find anything beyond helping Nintendo shift boxes.

Donkey Kong Country on the Super Nintendo is a good example. It gets regular mentions in game histories because it sold loads and gave Nintendo the advantage over Sega for a while. But what did Donkey Kong Country really add to the medium of video games? What did it do to deserve to go down in history as an important game? I’m open to suggestions, but I couldn’t find anything beyond helping Nintendo shift boxes.

By viewing games as mere ammunition in the console wars we undervalue the games themselves. We overlook the obscure, but influential, and overplay the popular, but ultimately uninfluential. It is like film history, giving more attention to Police Academy 3 than Three Colors: Red.

The console generation structure of video game history is also limited in that it ignores other gaming platforms. The PC is the ultimate example of this. PCs do not have generations. They are a hardware continuum that dates back to when IBM launched the first PC in 1981 and runs right through to the present day. Android and Apple smartphones are another example. Yes, these devices have generations, but so many in such a short space of time that it’s almost meaningless to talk about games of different iPhone generations.

An overfocus on consoles also results in whole game genres being shut out of the historical narrative. Genres like text adventures. The legacy of these text-only games can still be felt today. Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead and Double Fine’s Broken Age are two obvious recent descendants of the text adventure, but the genre also helped spawn visual novels and massively multiplayer online role-playing games. But text adventures did not exist on consoles so the console generations model makes us look at game history in a warped way and runs the risk of crucial developments being missed.

An overfocus on consoles also results in whole game genres being shut out of the historical narrative. Genres like text adventures. The legacy of these text-only games can still be felt today. Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead and Double Fine’s Broken Age are two obvious recent descendants of the text adventure, but the genre also helped spawn visual novels and massively multiplayer online role-playing games. But text adventures did not exist on consoles so the console generations model makes us look at game history in a warped way and runs the risk of crucial developments being missed.

The console generation model also feeds into the third problem I had with video game history: the emphasis on technology over creativity. A lot of what I read before starting Replay seemed to frame games as almost a side effect of technology. Now I’m not denying for a moment that technology shapes games. It clearly does. Technology imposes limits and pushes and pulls game design in different ways, but this is true of all media. Film is molded by camera and screen technology. Music is shaped by instrument design and recording technology. But do we seriously believe that Jimi Hendrix is a side effect of Fender? Of course not.

Technology is just a tool and it’s only when people do something creative with it that we get something exciting. So I wanted Replay to treat games as a subset of culture, not a subset of technology. It felt like more accurate a perspective to me and, frankly, people are so, so much more interesting than bits and bytes and circuit boards and USB sockets.

Another frustration was that these histories tended to treat games as if they existed in a bubble. It was as if the video game had transcended to the spirit plane and was now somehow a law unto itself, unaffected by the ups and downs of the world around it. Yeah, right. Geopolitics, economics, international trade, politics and social trends – they all affect games. The rise of South Korea as a force in video games and the creation of free-to-play games is a story of economic crashes, war, Korean-Japanese relations, poverty, credit card access and social attitudes to copyright law.

If gaming history does not consider the wider historical context, then it is almost certain we will misinterpret things. Without that context, we end up talking about how Atari’s VCS game E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial caused the North American video game industry crash in the early 1980s because we assume that the only factors in play are those of the game industry’s own making.

But when we look more broadly there is an often overlooked factor in the crash: the VCR. Today, it’s hard to remember how amazing a device this was at the time. It’s 1983 and now you can buy a device that lets you record TV and watch it whenever you want. What? I don’t have to plan my day around my favorite TV show to make sure I’m watching when it is broadcast? What? I can watch that show as many times as I want? What? I can go and buy or rent a cassette that lets me watch my favorite movie ever? A movie I’ve only seen twice seven years ago because my local cinema hasn’t shown it since it came out? What’s more, the VCR was also something everyone in the family was going to enjoy too.

So what are you going to spend your money on? A VCR or another chase the red-square-with-green-dot games machine? It’s an easy choice. That the VCR took off at the same time as the wheels fell off the games industry in the US is unlikely to be mere coincidence and is probably a bigger factor than one disappointing VCS game, no matter how high profile.

The final thing that bugged me about these game histories was the cheerleading. It was all, ‘Games! Games are good! Games are great! Ra! Ra! Team Game! Yay!’. In these histories, games could do no wrong. There were critics, but they were presented like bogeymen. People like Dr Everett Koop, the US Surgeon General, who criticized games in 1982, or US Senator Joe Lieberman, whose campaign against violent games in the mid-’90s led to the creation of the video game age ratings system in the USA.

This bugged me because I think history should try to be objective. It is a goal history should strive for, even if it is unattainable. What’s more, even the enemies of video games influence the history of the medium. Joe Lieberman’s campaign changed the games industry in North America, no question. Dr Koop was vocalizing what a great many people felt about games in 1982. Surely the attitude of non-players towards games is as much part of the history of the video game as the stories about the game makers, game companies and players? Just because we might disagree personally does not detract from their role in the medium’s history. So I wanted Replay to cover the awkward moments too, the moments where games got a kicking, the uncomfortable aspects of the gaming world, be that games as vile and offensive as RapeLay or the political crusades against violent games or the misogynistic abuse women get while playing online.

As you can probably tell by now, Replay was largely a reaction to what I felt was lacking elsewhere. But those issues with previous game history led me to come up with five goals for Replay – a kind of manifesto for what I wanted it to do with the book in terms of how it looked at the subject.

First, Replay would be a global history. It would pay attention to and recognize the differences in the video game histories of different countries. Second, it would focus on trends in game design, picking out how game genres evolved over time and the stylistic movements within them. Third, it would emphasize game design trends over business and technology in the narrative. Although not to the exclusion of business or technology because both are so interwoven into gaming history that it would nonsense to try and write them out of it. Fourth, it would seek to be as objective as possible and not assume games are infallible. Finally, Replay would look at games that were important or influential, not just those that sold well.

So how did I go about doing this? The research for Replay can be divided into three rough stages. In reality, it was a messier, less linear research experience than I’m going to describe here as these stages often overlapped, but these stages capture the essence of my approach.

First, I did a huge trawl through as many sources as I could lay my hands on. I played old games and read magazines, newspapers, newsletters, books and websites. I watched videos of gameplay on YouTube, read advertisements, company reports and old memos. I went through game manuals, walkthroughs and old video game catalogues. I also compiled spreadsheets where I tried to list every game made on every platform ever with details of that game’s release year, publisher, developers, country of origin, genre, scenario and other notable things about it. From this I ended up with well over 1,000 pages of A4 in notes and a collection of spreadsheets listing tens of thousands of games.

The next step was to try and use this raw information to spot links between games and events and people in the hope of identifying patterns in video game history. Essentially, I was trying to piece together an evolutionary tree or, more accurately, draw a very messy, complex mind map of how everything connected together.

From doing this, common features and paths in game design started to come into focus. For example, there was a sizeable lump of British games from the 1980s, and to some extent in the 1990s, that stood out as being, well, a bit odd. Games like Head Over Heels, a puzzle-focused game where you collect donuts and purses while avoiding Daleks that have the head of Prince Charles, or Monty on the Run, where you play a fugitive mole who is wanted for stealing coal from a trade unionist’s secret mine and must avoid deadly teapots.

|

|

And weirdest of all Deus Ex Machina, a game based on Shakespeare’s As You Like It where you play a mouse dropping that challenges a Brave New World-like dictatorship. Deus Ex Machina also came with an audio cassette that played a soundtrack featuring British TV celebrities like Frankie Howerd and songs about being a sperm that dreams of fish and chips. I’m really not making this up.

Now other countries have oddball games too, but there were several things that stood out about these strange British games. First, there were more of them than in other countries. Second, the strangeness seemed to be an aesthetic trend that could be seen in many different genres of games. Third, these games were usually based around some kind of almost everyman hero. So while American games tended to put you in the shoes of great warriors or brave action heroes, British gamers in the 1980s got to play the role of bin collectors, thieving moles, laser-spitting llamas or a mouse poop. But most crucially of all these games were mainstream. In other countries, strange off-the-wall games tended to be niche, but in 1980s Britain, they were very much part of the mainstream of gaming. Given this, it seemed reasonable to think that there was something different happening in the UK at that time compared to other places.

Another example is the rush of games aimed at girls in the mid-1990s, such as Barbie Fashion Designer and Chop Suey. Games aimed directly at girls existed before then, but were few and far between, yet in the middle of the 1990s there was a sudden spate of them. That suggested there was some kind of movement at the time, something going on that caused this trend.

Another example is the rush of games aimed at girls in the mid-1990s, such as Barbie Fashion Designer and Chop Suey. Games aimed directly at girls existed before then, but were few and far between, yet in the middle of the 1990s there was a sudden spate of them. That suggested there was some kind of movement at the time, something going on that caused this trend.

But me drawing these links was all very well, but I also needed to ensure that the evidence was there to support my ideas about movements, trends and the other connections I thought I saw. So I sought to test these theories of game history to try and work out what was true and what was false. I took a civil court approach to this. For something to be – so to speak – proved, it had to pass a balance of probabilities test. In short, the evidence supporting it had to outweigh the evidence against it.

For example, from my research I knew that the space-trading game Elite was a direct influence on Grand Theft Auto. The developers of Grand Theft Auto had said so publicly several times and this was later reconfirmed when I interviewed a couple of them. But then there was this other game Hunter, an Atari ST and Amiga game released in 1991.

Hunter had a third-person perspective, different weapons to use, an open 3D world to explore and different vehicles to travel around in. You could play it by following the missions or just explore and mess around in its 3D world. In short, it offered the core elements of Grand Theft Auto III, but 10 years earlier. So my theory was that Hunter was an influence on Grand Theft Auto too. It seemed reasonable. Grand Theft Auto III’s creators, the Scotland-based DMA Design or Rockstar North as they are now known, were active in the industry around the time that Hunter came out. And while Hunter did not sell well, it got a good amount of coverage in UK game magazines, so it was reasonable to think that at least some of the people who went on to make Grand Theft Auto III would have come across Hunter. But I could find no evidence from my interviews or elsewhere that this largely overlooked game helped inspire Grand Theft Auto III and so that theory was dropped. Pioneering as it was, Hunter doesn’t matter. It was an aberration, a one-off. Hunter may have given people a glimpse of gaming’s future, but it did little to create that future.

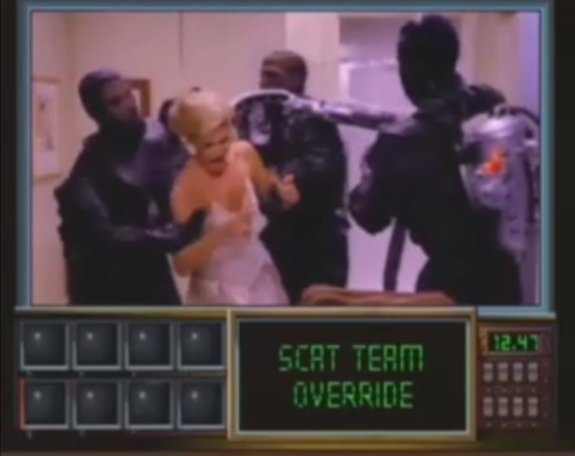

As well as looking out for games that seemed to be part of a trend or had influenced other games, I also looked for games that were of wider significance to the history of the medium. Games like Death Race and Night Trap. Released in 1976, Death Race is a coin-op video game where the goal was to score points by running over pedestrians. Night Trap, meanwhile, was one of the many mid-1990s games that were based around the video playback functions of CDs – full-motion video games as they were called back then. The game required players to protect a group of women

As well as looking out for games that seemed to be part of a trend or had influenced other games, I also looked for games that were of wider significance to the history of the medium. Games like Death Race and Night Trap. Released in 1976, Death Race is a coin-op video game where the goal was to score points by running over pedestrians. Night Trap, meanwhile, was one of the many mid-1990s games that were based around the video playback functions of CDs – full-motion video games as they were called back then. The game required players to protect a group of women  having a slumber party from vampires who plan to break in and steal their blood. To do this the player had to spy on the women via hidden cameras and planting traps for the vampires. Good taste wasn’t a strong point for Night Trap. Neither of these games were influential in terms of game design, but both caused moral panics that became defining moments in video game history. Death Race caused the first media panic about games and also helped show the industry that controversy sells more games. Night Trap, together with Mortal Kombat, so incensed US Senator Joe Lieberman that he started a congressional hearing into it and other violent games. As a result of those hearings, the games industry in the US started putting age ratings on games, which in turn had consequences for what games were made.

having a slumber party from vampires who plan to break in and steal their blood. To do this the player had to spy on the women via hidden cameras and planting traps for the vampires. Good taste wasn’t a strong point for Night Trap. Neither of these games were influential in terms of game design, but both caused moral panics that became defining moments in video game history. Death Race caused the first media panic about games and also helped show the industry that controversy sells more games. Night Trap, together with Mortal Kombat, so incensed US Senator Joe Lieberman that he started a congressional hearing into it and other violent games. As a result of those hearings, the games industry in the US started putting age ratings on games, which in turn had consequences for what games were made.

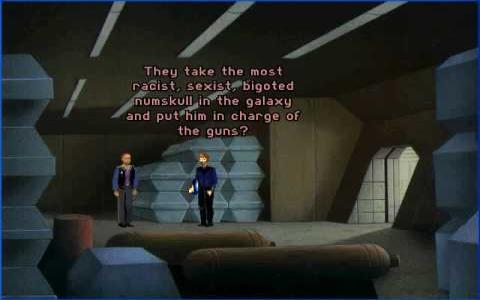

Another example of a game that had a wider significance for the industry is the 1996 point-and-click adventure game The Orion Conspiracy. If you judged it on game play alone it wouldn’t be worth a mention, the game is a bog-standard point-and-click adventure. But it is notable for being one of the very first games to include a positive and overt portrayal of homosexuality in its narrative and so broke new ground in video games.

Another example of a game that had a wider significance for the industry is the 1996 point-and-click adventure game The Orion Conspiracy. If you judged it on game play alone it wouldn’t be worth a mention, the game is a bog-standard point-and-click adventure. But it is notable for being one of the very first games to include a positive and overt portrayal of homosexuality in its narrative and so broke new ground in video games.

So the final stage of my research for Replay was to try and back up my conclusions. The 140 or so interviews I did with game designers and others involved in game history was the primary I did this, but I also did another trawl through the reading material I had, as well as reading more sources that could answer specific questions. Some ideas failed, like the connection between Hunter and Grand Theft Auto III or my initial thought that all those weird British games were the product of drugs. To the disappointment of the journalist in me, it turned out that progressive rock and Monty Python’s Flying Circus were – by and large – the inspirations behind those games. That’s not a bad story, but I was rather hoping for some saucy tales of game designers on LSD creating whacked out games for school kids. Ah well.

Another thing I did during this stage was to try and fact check the information that was contradictory or seemed too good to be true. Stories like the Atari VCS game E.T. being the cause rather than a symptom of the problems that caused the US game crash in early 1980s, which seemed less and less likely as I looked deeper into the causes of the industry’s downturn.

This approach didn’t always work out. Let me give you an example. There’s a story about Taito’s coin-op game Space Invaders that goes that it became so popular in Japan that it caused a coin shortage in the late 1970s. My gut instinct was this was nonsense – the story stank of spin. So I spent a fair bit of time trying to prove it wrong. But one of the earliest mentions of the coin shortage was in New Scientist, hardly an unrespectable publication (Cunningham, 1980). On top of that the Bank of Japan told me that they couldn’t find a record of the shortage and so could not say if it was true or not. Eventually I ran out of time and I still hadn’t found anything that seriously challenged the story of the Space Invaders coin shortage. So into the book it went. But it’s not true. Since then, Paradis (2014) has finally busted that myth by getting solid evidence that it isn’t true, including confirmation from both the Bank of Japan and Square Enix – the current owners of Taito – that it never happened.

This approach didn’t always work out. Let me give you an example. There’s a story about Taito’s coin-op game Space Invaders that goes that it became so popular in Japan that it caused a coin shortage in the late 1970s. My gut instinct was this was nonsense – the story stank of spin. So I spent a fair bit of time trying to prove it wrong. But one of the earliest mentions of the coin shortage was in New Scientist, hardly an unrespectable publication (Cunningham, 1980). On top of that the Bank of Japan told me that they couldn’t find a record of the shortage and so could not say if it was true or not. Eventually I ran out of time and I still hadn’t found anything that seriously challenged the story of the Space Invaders coin shortage. So into the book it went. But it’s not true. Since then, Paradis (2014) has finally busted that myth by getting solid evidence that it isn’t true, including confirmation from both the Bank of Japan and Square Enix – the current owners of Taito – that it never happened.

This is one of the issues with doing a large, all-inclusive, narrative history. There is so much ground to cover that if you ever hope to finish writing it there are points where you have to say, ‘that’s it, I cannot spend any more time looking into this topic because it will only form a sentence in a 100,000-word plus book’. As such you are – as is often the case with history – somewhat reliant that the people who came before got their facts right. Much of the time they do, but not always. That’s the first lesson from writing Replay.

Another lesson is that primary sources and sales figures about historic video games are hard to find. The situation seems to have improved a lot since I started working on Replay, thanks to the efforts of various museums around the world, but tracking down good amounts of primary source material was and probably remains tough, not least because a lot of that material – assuming it ever existed – has been thrown away, dumped in skips as game companies shut their doors or decided to have a clear out. Sales and in-depth financial figures are even harder to get and that’s annoying. People often talk about successful games, I’ve probably done it myself, but what exactly is a successful game? Is it one that sold lots of copies? If so, how many copies is a lot of copies? Is it one that made a profit? If so, how much profit is a successful profit? Doesn’t that depend on what you spent making it? Maybe it is one that was popular with critics? If so, is every critic equal? Or could it be one that the developers were happy with? If so, was it successful from anyone else’s point of view? Or is it a game with a lot of likes on Facebook? If so, how do we work out how many of those likes were bought and does such a passive, non-demanding action as liking something on Facebook really carry any weight? Having good sales and financial information would do a lot to help game historians pinpoint what is meant by the term success and get the historical context right.

A third lesson is that while Replay did look at the stories of players, there is a lot more history to uncover there. Not just in the sense of how communities of players form and influence things, but also in how players play. I was speaking with the developer Wargaming.net a few months back for the foreword of the Russian language edition of Repl ay. They told me how, based on the data they get from World of Tanks, they can see differences in the playing styles of people in different countries. So someone in Italy plays differently from someone in Russia, who in turns plays the game differently from someone in Canada. I think that’s really interesting and these days game companies have huge databases that show very precisely how people play. That data has the potential to open up so many avenues for game history researchers to explore and – best of all – will provide very strong measurable evidence about shifts in playing patterns over time. The question is: will game companies open these commercially valuable databases to those researching game history?

ay. They told me how, based on the data they get from World of Tanks, they can see differences in the playing styles of people in different countries. So someone in Italy plays differently from someone in Russia, who in turns plays the game differently from someone in Canada. I think that’s really interesting and these days game companies have huge databases that show very precisely how people play. That data has the potential to open up so many avenues for game history researchers to explore and – best of all – will provide very strong measurable evidence about shifts in playing patterns over time. The question is: will game companies open these commercially valuable databases to those researching game history?

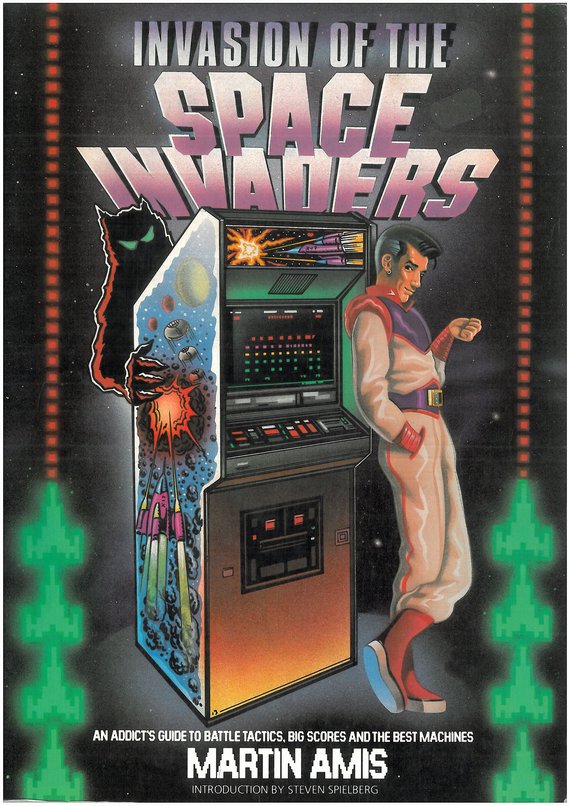

Another lesson is that it is hard to see the wood for the present-day trees. In other words, you can’t see video game history as it happens. The closer something is to now, the harder it is to see where it fits into the wider historical narrative. Take this opinion on the original Donkey Kong that the author Martin Amis gave in 1982: “I have a vision in which this machine is perched on top of the Empire State Building and is inexorably strafed into destruction. Donkey, your days are numbered. The knackers’ yard awaits you.” (Amis, 1982, p. 82)

Another lesson is that it is hard to see the wood for the present-day trees. In other words, you can’t see video game history as it happens. The closer something is to now, the harder it is to see where it fits into the wider historical narrative. Take this opinion on the original Donkey Kong that the author Martin Amis gave in 1982: “I have a vision in which this machine is perched on top of the Empire State Building and is inexorably strafed into destruction. Donkey, your days are numbered. The knackers’ yard awaits you.” (Amis, 1982, p. 82)

As far as Amis was concerned, Donkey Kong was a worthless game, something that would soon be forgotten. Given what we know now about Nintendo and Mario, it’s about as wrong as you can get, but no-one at that time could really have foreseen what Donkey Kong had started.

So identifying what recent games matter is very tricky. It’s probably safe to say Minecraft matters in game history at this point, but what about Papers, Please or Skylanders? They appear to be significant, but it’s too early to be sure. Maybe the most important game of our time is one we’re ignoring or have dismissed. Maybe it is one that only few people are playing and we won’t find out how important it was for another 10 years when the people playing it now enter the games industry and make games inspired by it. That was certainly true for MUD, the original online multiplayer role-playing game – its significance only really came to the fore in the late 1990s almost two decades after it was created.

My fifth ‘lesson’ is more a thought for the future. Since Replay came out, there has been an explosion in the number of new games. Smartphones, indie games and social games were only just taking off when I was writing Replay. This explosion in the volume of new games presents a serious challenge. It makes it harder to keep on top of what is being released and then work out what trends there are. The shift to digital sales of games is another challenge because games are no longer fixed works. They get constantly updated and some games get removed and vanish. That will likely be a problem that game historians will be facing when they come to write about the game history of today.

The final lesson from Replay is that time runs out. The man in the photo (on the right) is Jerry Lawson, the inventor of the Fairchild Channel F – the first cartridge and microprocessor-based game console. It was the template for pretty much every console that followed its release in 1976. I spent ages trying to track him down and eventually found a postal address for a Jerry Lawson in California that I thought was him, although it could well have been the home of some random person with the same name. So I sent him a letter in the post and waited. Nothing. Eight months passed. Still nothing. Maybe it was another Jerry Lawson, I thought. Then about two weeks before I finished writing Replay, an email pops into my inbox from Jerry. Sorry, he says, I just found your letter, but I’m up for talking. Time was tight at this point. So with my deadline looming, I worked out where his comments would best fit into the near-finished book and did a shorter than normal interview. Jerry was great. Funny, insightful, interesting and full of great stories. I remember putting down the phone and thinking that if I get the chance to do a second edition of Replay, I should interview him again, properly.

The final lesson from Replay is that time runs out. The man in the photo (on the right) is Jerry Lawson, the inventor of the Fairchild Channel F – the first cartridge and microprocessor-based game console. It was the template for pretty much every console that followed its release in 1976. I spent ages trying to track him down and eventually found a postal address for a Jerry Lawson in California that I thought was him, although it could well have been the home of some random person with the same name. So I sent him a letter in the post and waited. Nothing. Eight months passed. Still nothing. Maybe it was another Jerry Lawson, I thought. Then about two weeks before I finished writing Replay, an email pops into my inbox from Jerry. Sorry, he says, I just found your letter, but I’m up for talking. Time was tight at this point. So with my deadline looming, I worked out where his comments would best fit into the near-finished book and did a shorter than normal interview. Jerry was great. Funny, insightful, interesting and full of great stories. I remember putting down the phone and thinking that if I get the chance to do a second edition of Replay, I should interview him again, properly.

Jerry died in April 2011, about a year after I talked to him. I never did that second interview. I missed my chance. And that’s a reminder to everyone involved in researching and writing about game history. The thing is we are very lucky historians, us game historians. The vast majority of people who created and built this medium are still with us. The eyewitnesses, the movers, the shakers, the visionaries, the enemies of games, the people who made game history. Most of them are still alive.

But they won’t be with us forever. Most historians have to piece together history from the fragments and trash left behind by previous generations. We game historians don’t. We can pick up the phone or Skype or email or go visit these people and capture their stories.

These oral histories are really important. The questions historians will want to ask game designers about their older works are very different from the questions journalists will want to ask them about their current work. The purposes are different and the context is different too in that the designer will be talking to the press to help sell his or her game so we cannot rely on journalists to cover the ground that will be valuable when looking back at game history.

The game historians who will follow us all in 20, 30 years’ time won’t have the chance to speak to many of these people. And that’s both a privilege and a pressure for everyone involved in recording and writing game history today. It’s a pressure because it means there’s something of a duty on us to make sure we don’t let that opportunity to speak with the people who built the medium in its formative years slip through our fingers. But it’s also a privilege because we’re the game historians at the start, the ones who will capture the resources that later historians will use and the ones who will help set the course for how game history is remembered and viewed in the future. Which is why I can’t help but feel that being involved in video game history right now is something truly exciting to be a part of.

Bibliography

AMIS Martin (1982), Invasion of the Space Invaders, London, Hutchinson.

CUNNINGHAM Chris (1980), “The games that aliens play”, New Scientist, 18-25 (December), p. 782.

DONOVAN Tristan (2010), Replay: The History of Video Games, Lewes, UK, Yellow Ant.

DONOVAN Tristan (2013), Fizz: How Soda Shook up the World, Chicago, Chicago Review Press.

PARADIS Charles (2014), “Insert coin to play: Space Invaders and the 100-yen myth”, The Numismatist, March, p. 46-48.

Tristan Donovan is a British journalist and the author of Replay: The History of Video Games (2010), Fizz: How Soda Shook Up the World (2013) and Feral Cities: Adventures with Animals in the Urban Jungle (2015). He has also contributed chapters on video game history in Video Games Around the World (2015) and The Routledge Companion to British Media History (2014). Tristan’s games journalism has appeared in Stuff, BBC News, Eurogamer, Gamasutra, Edge, The Times (of London) and The Guardian. He has also edited the following books: Generation Xbox: How Video Games Invaded Hollywood by Jamie Russell (2012) and Death Threats and Dogs: Life on the Social Work Frontline (2013).