Volume 5, Issue 1, December 2015

Geoffrey Rockwell & Keiji Amano

University of Alberta / Seijoh University

Introduction

The sound is overwhelming. The balls fall vertically against the pins making a cascade of noise; the massed balls falling into the waiting tray create a cacophony.

In this aural inferno sit long lines of patrons, each before his own machine, oblivious of his neighbour. One thinks of the word of the nineteenth-century factories, humans themselves half machine; the assembly line gone mad. Looking at the busy hands, the empty eyes, one also thinks of some kind of religious ceremony, something vaguely Tibetan with mandalas plainly visible and the prayer-whieels whirling. (Richie, 1992, p. 226)

Like the film critic Donald Richie, most Westerners visitors to Japan who notice pachinko are overwhelmed by it. Roland Barthes, in his book on Japan, Empire of Signs, devotes a short chapter to this “collective and solitary game.” (Barthes, 1982, p. 27) Once you notice pachinko you discover parlours everywhere occupying the prime real-estate at the intersections of major thoroughfares in Japanese cities. These parlours have large and glittery entrances inviting you into a space of play unlike the arcades. You are assaulted by the noise of thousands of steel balls falling through pins, and the grey smell of cigarettes burning in the small ashtrays at each console. You walk down rows of brightly decorated vertical consoles, careful not to trip on the trays of shiny balls won by players, and young aides greet you politely while you try to figure out this popular game. What you may not know is that pachinko is the most popular game in Japan and yet it is rarely discussed in game studies there or even in the Japanese literature around game culture. It is the most popular of a small number of licensed gambling games.[1] It is a game apart, both economically and culturally, which makes it worth exploring. This paper will look at pachinko from a game studies perspective, by which we mean as a game. We will explain why we are taking a game studies perspective, discuss how pachinko works, outline its history, its cultural context, economics and the aesthetics of pachinko. At the end we will return to the oriental strangeness of pachinko as a site to explore some of the dangers of cross-cultural game studies.

Why Pachinko?

Pachinko is not your typical genre of coin-swallowing arcade game but one of the legal Japanese “gambling” games which is why we need to start by making the case for looking at it from a game studies perspective as a game rather than as a gambling phenomenon. That is not to say that pachinko shouldn’t be studied by gambling researchers[2], just that we will take a ludic perspective.

Our reasons for treating pachinko as a game are first, pachinko has evolved into a transmedia phenomenon drawing on and feeding popular manga, anime, and video game franchises. Video games in Japan repurpose and bleed into the content of other forms of entertainment from cards to anime and even to pachinko.[3] For example, thinkers like Azuma (2009) talk about the consumption of moe characteristics across media as paradigmatic of postmodern otaku consumption. It is therefore worth thinking about pachinko as if there wasn’t a clear a line between games and other leisure media.

Second, we need to explore the grey areas of play between games for fun and gambling. Just because it is possible to win things in pachinko doesn’t mean that it isn’t played as a game for the fun of playing. Pachinko is a particularly interesting case of this grey area as it is technically illegal to gamble in Japan and pachinko is technically not gambling, though it has many of the features of gambling. It is, in some ways, pure gamification for bling.

Third, pachinko is a useful site for exploring cross-cultural game studies as it is an intranational phenomenon, not an international phenomenon. Foreigners, like Roland Barthes and Donald Richie have focused in on pachinko as an obvious difference between Japan and the West and that appearance of difference is worth exploring as it may tell us something about cross-cultural research in games. Lastly, it is an economically significant leisure industry, by some calculations (Sibbitt, 1997), accounting for over 3% of Japan’s GNP and surpassing even the automobile industry in the 1990s. This is how many Japanese play out their leisure time.

How Does Pachinko Work?

Pachinko is related to pinball in that the player fires steel balls that arch over a playfield to then drop through pins and other obstacles. In pachinko the playfield is vertical and the goal is not to keep a ball in play, but to get balls into special “win pockets” or “start pockets” that win you more balls or start a video slot game. Any ball that doesn’t make it into the win pocket is lost. Therefore when playing, you try to fire balls so that they fall through the pattern of pins, gates, spinners and chutes with the greatest likelihood of dropping into the win pockets. You do this by controlling the force with which the balls are launched. In older and simpler games the odds were simple; in an ALL-15 game you would get fifteen new balls for every ball that made it into one of the eight win pockets. If you were good or if the machine you were playing on had pins subtly out of alignment so as to increase your odds, then you would win more balls than you fired, leaving the pachinko parlour with prizes that could be exchanged for money.

Pachinko goes back to games like the “Corinthian Bagatelle”, a common predecessor to both pinball and pachinko. This child’s game was imported to Japan in the early 1920s and sweet shop owners began to set up the game to draw in children with the opportunity to win candy. One theory of the origin of the name is that children took to giving the popular game the onomatopoetic name “Pachi-Pachi” after the sound of the balls. Another source of the name “pachinko” that also makes sense for the game is that it means “catapult” in Japanese. When the game became popular among adults glass was added so that it could be stood upright, thereby saving space. In 1937 production of game machines was halted as materials and workers were needed for the war with China and parlours closed down; production didn’t resume until 1946 when parlours reopened in Nagoya. In 1948 Shoichi Masamura introduced the “Masamura Gage” where balls could bounce around and fall into multiple win pockets instead of falling through mostly vertical paths. The ALL-15 introduced by Masamura in 1950 had 8 win pockets paying out 15 balls each and it became a widely imitated standard for years.[4]

Today there are three types of games commonly available, the hanemono, the digi-pachi, and the kenrimono. In the 1970s the hanemono (“wing” + “thing”) type of game became popular because of a number of electromechanical features.[5] First of all, it fired balls automatically. All you had to do is turn a throttle that controls the force with which the balls are launched so as get the balls to fall where you want them to. Before that you had a handle that manually launched balls. This had the effect that you could spend a lot more balls in a period of time, therefore increasing the amount spent per hour on a machine, something the parlour owners obviously wanted. Second, there were a number of special pockets which, when a ball landed in them would open gates or flippers for a few seconds that could channel more balls into the win pocket. Newbies and foreigners are encouraged to start playing on these as they are easier to understand.

Competition from video games in the 1990s led to the development of digi-pachi games (portmanteau of digital + pachinko). These have a LED screen in the middle of the playfield which adds animations and slot-like odds to the game. When you get a ball in the win pocket it starts the video slot machine that you have the same control over as you would with regular video slots. Depending on what combinations you get at the slots you can dramatically increase the payout in balls starting a “fever” round where each ball in a win pocket pays out a higher ratio of win balls, which, of course, encourages you to fire even more balls spending more money.

A third and rarer type of game is the kenrimono that has complex rules governing the changing odds and sequencing of open gates. These games are less accessible to all but “pachipros” (pachinko + professional) as the odds of winning under normal conditions are less, but if you understand the complex sequencing then you can win much larger payouts under the right conditions. As a result these games are for the hard-core pachinko players who like to think they can game the games.

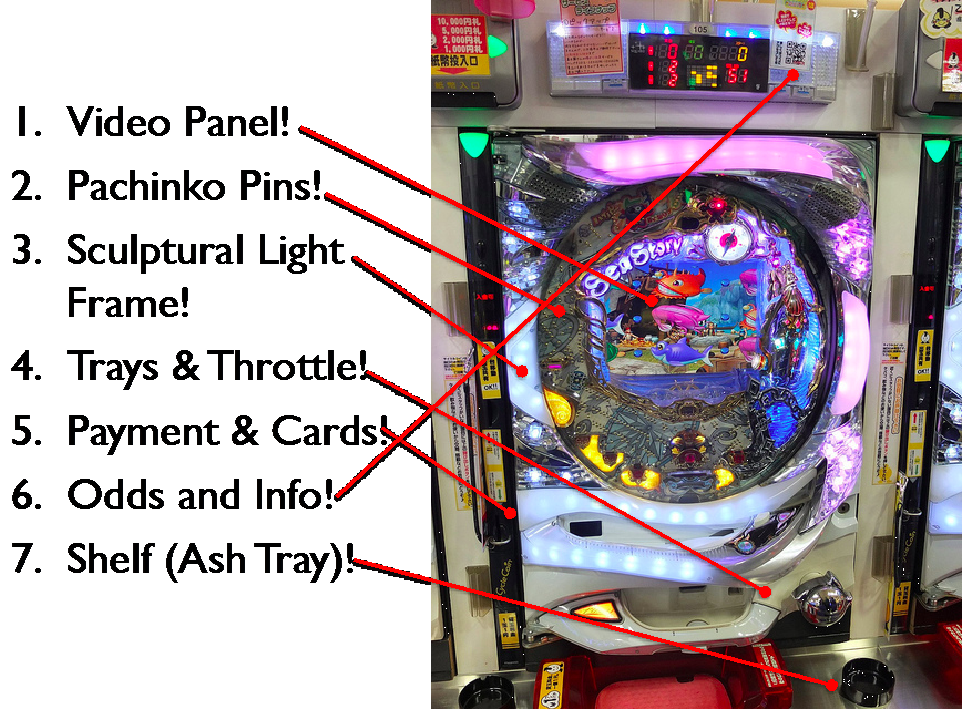

In this image you can see the larger visual field of a pachinko game.[6] To play you put money in the slot for bills (5) that pours balls into your upper tray (4). You turn the throttle (4) to fire the balls that emerge near the top around (2). You control the force with which the balls are fired to try to get them to drop in a gap right around the top rather than shoot over the top to the right. The balls fall and if you are lucky some drop into the start pocket which triggers the video slot on the LCD screen (1) in the centre which you control with a button to the left of the lower ball tray (4). As you win balls they fall into the upper tray (4) and then cascade into a lower tray from which you can release them into special removable trays that can then be stacked next to your seat. Above the game there is a panel (6) that tells you the statistics for this machine and lets you call for an attendant for help with your trays of won balls. At the bottom is a shelf with an ashtray (7).

Pachinko and Gambling

What do you do with the balls you win? This leads us to step back from the game itself and talk about the ludic context of pachinko, both the laws, spaces and pace of the game. In Japan gambling is technically illegal, but there are a number of games including pachinko where it is possible to gamble indirectly for money. The way it works in pachinko is that you can redeem the balls for prizes in the pachinko parlour and the prizes for money outside the parlour. These prizes can be snacks, cigarettes, lighters, on up to electronics, though the police can set limits to the value of the prizes. You can also get special tokens that, along with the prizes, are redeemable at small and discrete exchange parlours outside the pachinko parlour for real money. The exchange shops are supposedly independent of the parlours, thus the parlour isn’t letting you gamble for money, only for prizes and it is someone else that redeems the prizes.

As the exchange rate isn’t what you pay for the balls, you don’t make much money from pachinko, even when you win, but there are lots of flashing lights, sounds, bling and prizes on the way, which is the zone a player try to get into. There is probably no other game where you get so much spectacle for your yen, but more on this later. Sibbitt (1997, p. 569) estimates that balls bought for 4 ¥ each yield 2.5 ¥ once redeemed back for money. If you simply bought 1000 ¥ worth of balls, walked over to the prize counter to trade them for prizes, and then took the prizes out to the shop to get your money you would get 625 ¥ back, and that is without losing any balls in the playing. This is why the odds in the pachinko game itself can be quite good; once you buy balls you have already accepted an entertainment exchange loss.

The economics of pachinko are beyond the scope of this paper, but a few things need to be mentioned in order to understand the reach of the game. David Plotz in his report to the Japan Society on Pachinko estimates in USD that “Thirty million Japanese play pachinko and pachislo every year, dropping more than $200 billion in the machines, and losing around $40 billion of it.” Sibbitt (1997) reports that the pachinko industry accounts for 4% of the gross national product and according to the « White Paper on Leisure 2013” (published by the Japan Productivity Centre), the size of the leisure market in Japan is about 65 trillion ¥ (in 2012) of which pachinko is 28% of that market (19 trillion ¥ or USD $ 242 billion).

Also important is the deep involvement of the Japanese National Police Association and local police in the industry (Johnson, 2003; Sibbitt, 1997). The police license pachinko parlours and regulate them in various ways. Sibbitt (1997) writes that “The industry’s hazy legal status and expansive police power over the pachinko business, when combined with the industry’s vast wealth, provide a systemic formula for police corruption and conflicts of interest.” (p. 577) He goes on to suggest that for many police, pachinko is a form of retirement fund and that the police therefore resist attempts to change the legal status of pachinko. It is in the interest of the police to have a large pachinko industry whose legal status is dependent on them. Just as in many Western countries the state is now “addicted” to gambling for revenue, especially since the 2008 recession, so too the Japanese state through its police seems to be addicted to pachinko.[7] Interestingly the police also regulate the game in ways that affect game play, especially when there are flare-ups of public concerns about addiction. From a ludosociological perspective where one looks at how play is structured in society, it is important to note the effects of police regulations that set, for example, the maximum rate of balls fired per minute, as these affect the game itself. It is also important to note that pachinko is a sanctioned form of neighborhood gambling that is out in the open and generally tolerated, in part because it is regulated.

The Culture and Space of Pachinko

As for the actual space and pace of the playing, it is helpful to compare pachinko parlours to Japanese game centres (or arcades.) Game centres are typically narrow vertical buildings in the center of town with multiple floors each of which might be dedicated to a different type of game and therefore audience. Game centres will have crane games (UFO catchers) on the ground floor to bring in couples, photo booths for girls, and dark upper floors with the men’s fighting games, darts and other pleasures. Pachinko parlours by contrast are bright, usually on one floor you can just walk into, wide open, and all over the city. The games will be divided by corridors, some appealing to men some to women, though women are still a minority of the players. Game centres are mostly for youth and in their heyday were an alternative place for youth to gather while pachinko parlours appeal to older Japanese and in their heyday provided a place of light, sound and relief from work. Pachinko parlours are not destinations the way game centres are, they are in the neighborhood so as to support both women players who want to drop in after shopping and before dinner or to support the hard working single salaryman who keeps loneliness at bay in the evenings by “squashing time” (Manzenreiter, 1998). They occupy a position in Japanese culture very similar to that of videoslots as documented by Natasha Schüll (2012), providing people a way to get into a “zone” where they can forget work and troubles.

In terms of games and using Caillois’s categories (1961) we would classify pachinko as a game that provides a combination of alea or the pleasure of chance and ilinx or the pleasures of illusion and vertigo. The role of chance in pachinko is obvious even though it doesn’t pay very well as far as gambling games go. Pachinko in this regard is like videoslots in providing constant engagement with chance. We suspect that they are designed the way videoslots are to provide regular wins and losses in a way that is addictive (Schüll, 2012). The odds are, however, managed – you never lose too much the way you might in high-stakes gambling. Pachinko is not about heroically confronting chance the way James Bond does on the casino floor. Pachinko is about a steady playing with odds that only leads to major losses if you are so addicted that you play for hours daily, which many do.

It may be less obvious how pachinko provides a form of ilix pleasure, or as we have called it, the pleasure of bling. Here is where we need to pay attention to visual theatre of pachinko. When you play pachinko you are in a fixed chair close to the vertical playing field. Even though you are in a corridor next to players on either side, the game occupies your entire visual field and the sound of the hall drowns out the sounds of others. You are effectively all alone and isolated from others. The visual field is also designed like a puppet theatre with a series of frames from the innermost video screen, to the pachinko pin field, to the sculpted and flashing frame, out to the frame of trays and controls (see Figure 1). Outermost are the mundane mechanisms for paying, calling attendants and holding your cigarette. Our point is that these nested frames completely capture your visual attention with a continuous display of flashing lights, shiny balls, and flickering video sequences, often played so fast you have to see them many times to parse them. It is a carnival for the eyes that you can dive into. It can swallow your attention and give you a sense of vertigo in the playful sense Caillois identified. This babble of visual bling is also why people lose track of time playing pachinko and get addicted to the distraction. From a game design, to understand the design of pachinko we theorize that one can analyze the different frames and how they are designed to interact.

Why Do They Play

One question that comes up over and over in essays on pachinko is why is it so popular? Why do so many people play Pachinko for so many hours? As Plotz (n.d.) puts it, “Why should people spend so much money and time on this strange activity when they could be playing video games or watching TV or, god forbid, socializing?” The addiction to the game baffles Western commentators in a way that it doesn’t seem to concern Japanese who are used to the omnipresence of pachinko parlours. It is worth surveying some of the answers.

First, it is argued that pachinko is a form of legalized gambling and is thus designed to be addictive the way video slot machines are (Dowling, 2005; Brooks, 2008). While pachinko may be particular to Japan, electronic machine gambling is addictive globally, though it may manifest itself differently. Natasha Dow Shüll in Part One of Addiction by Design describes how slot machines, video slots and video poker have been designed to be addicting to players. In fact, pachinko games now include video slot screens embedded into the playing field in a peculiar Japanese combination. For that matter the pachinko parlours now have rows of “pachislo” or Western-style slot machines too. Like pachinko games they pay out in prizes, not cash, but the designs are similar. One could thus read pachinko as a case of a local evolution of a global phenomenon. Local gambling regulations and police involvement led to the “neighborhood leisure” of pachinko in Japan while different conditions led to the “destination leisure” of Las Vegas casinos in the USA (Hirano & Takahashi, 2003). Las Vegas, if you think of it, is just as bizarre as pachinko.

Second, pachinko is an entertaining way to eat up time at the end of a tiring day. Pachinko is priced so that you could play it for hours without losing more money than the average person can afford. Plotz says that the games won’t let you lose more than USD $ 2 a minute. Much like bingo in Canada, it is way to “spend” your time with some hope of a winning. In a life of unremitting hard work, pachinko is an affordable form of evening relief. With the introduction of the digi-pachi “fever” games and the complex kenrimono games with potentially larger payouts, but ordinarily lower odds, this may no longer be true. In the newest shiny parlours the game is getting expensive to play, though you can win a lot more if lucky. As fewer people play pachinko leaving only a hard core, the industry seems to be evolving into something aimed more at the pachipros or committed players.

A related argument is made by Yoshiaki Naito (2000) who argues that the popularity of pachinko is due to leisure patterns in Japan where people don’t have the time for longer vacations. He writes, “As affluence increased, so too, proportionately, did the importance of knowing how to take advantage of the new perks (leisure time), but most people were at a loss. For these people, pachinko was an easy leisure option.” (p. 57) Many Japanese want leisure activities that are affordable, nearby, and fast. Pachinko is available in every neighborhood; you can nip in to play just a little or spend hours in the parlour; and it doesn’t cost much to start playing. In other words it is perfect for the hard-working salary-man or mother with a bit of time on their hands between chores.

Tanioka supplements this point by pointing out that in a Pachinko hall one can be alone for long periods of time. For men who don’t want to go home Pachinko can be a form of privacy. Donald Richie, who has written extensively on Japanese film and culture, compares it to the emptying of the mind of Zazen.

Like people in bars, those in the pachinko halls are feeling no pain. They are, rather, experiencing a kind of bliss. This is because they are in the pleasant state of being occupied, with none of the consequences of thinking about what they are doing or what any it means. The have learned the art of turning off. (Richie, 1992, p. 232)

Pachinko and Cross-Cultural Studies

As we have hinted above, pachinko fascinates Western commentators including the Canadian author of this article. To the Westerner pachinko is a sign of the difference of the other. It is hard not to be surprised upon first visiting a historic city like Kyoto when you notice that it is not quaint temples that dominate the landscape but enormous pachinko halls. In a country where real-estate is at a premium, it is common to find more than one premium corner of a major intersection taken up by a large pachinko hall. Nothing else gets so much space. They are the box stores of Japan. Thus it is not surprising that so many Westerners commenting on Japan like Barthes, Richie (and Rockwell) focus on pachinko.

Compared to the attention pachinko gets from Western visitors, to the Japanese this is an everyday phenomenon that is not particularly interesting unless there are unwanted socioeconomic outcomes. The subject crops up in Japan when a child dies left in a car because their addicted parents play for too long, or when the media reports that profits from pachinko are being funneled to North Korea. In general, however, the Japanese do not study gambling let alone pachinko. As Plotz puts it, “The Japanese government does not fund any research into gambling, and neither do gambling companies themselves. Only a handful of academics study gambling, and only a couple does it fulltime.” Plotz attributes the difference in interest in part to a difference in moral perspective. Gambling (and therefore pachinko) is not forbidden in any of the major Japanese religions. It isn’t a moral issue the way it is in countries with biblical moral traditions. This can be seen in government investment in research as in the West, as governments get addicted to gambling, there is a residual sense of guilt so, for example, in Alberta the government funds the Alberta Gambling Research Institute.

Certainly pachinko is no marginal phenomenon, nor is it the pursuit of a fringe group. It seems rather to emphasize the commercialized, industrialized, and bureaucratized character of play behavior in a mass society, as Japan is so commonly and so easily labeled. (Manzenreiter. 1998, p. 365)

We conclude by asking of our interest: Is this difference in attention to pachinko interesting itself? Is it not a touch of orientalism to draw attention to pachinko as a site of difference? Manzenreiter (1998) deals with the ways both Western and Japanese commentators have noticed that pachinko may be a uniquely Japanese form of gaming. We don’t believe it is orientalism to ask respectfully about major differences in gaming culture, especially if one collaborates in this research across cultures, but we do believe there are dangers to cultural generalizations that need to be always kept in mind. These dangers are the other side of the coin of the opportunities for leveraging insight from difference. If anything one learns more about one’s own culture when doing cross-cultural work. Finally, as we hope has been made clear, we believe that pachinko is a culturally unique expression of the more general phenomenon of neighborhood gambling that is comparable to videoslots. Pachinko has a unique history of regulation and police involvement which is fascinating, but in many ways fits in a gaming niche comparable to slot machines. Natasha Schüll’s (2012) careful study on how videoslots and their spaces are designed for addiction needs to be replicated for pachinko, but that is for another paper.

References

– (n.d.), « History of Pachinko », Pachinko Planet, Retrieved August 7, 2012, from http://pachinkoplanet.com/zencart/index.php?main_page=page&id=2&chapter=2.

AZUMA H. (2009), Otaku, Japan’s Database Animals, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

BARTHES R. (1982), Empire of Signs, New York, Hill and Wang.

BROOKS G., ELLIS T. et al. (2008), « Pachinko: A Japanese Addiction? », International Gambling Studies, 8:2, p. 193-205.

CAILLOIS R. (1961), Man, Play, and Games, New York, The Free Press.

COUNDRY I. (2009), « Anime Creativity: Characters and Premises in the Quest for Cool Japan », Theory Culture Society, 26:2-3, p. 139-163.

DOWNLING N., SMITH D., et al. (2005), « Electronic gaming machines: are they the ‘crack-cocaine’ of gambling? », Addiction, 100, p. 33-45.

ELLIS J. (n.d.), “What are the Different Types of Pachinko Machines?”, wiseGEEK, Edited by Bronwyn Harris, Retrieved August 7, 2012, from http://www.wisegeek.com/what-are-the-different-types-of-pachinko-machines.htm.

HIRANO K. & TAKAHASHI K. (2003), « Trends of Japan’s Giant Leisure Industry: Pachinko », UNLV Gaming Research & Review Journal, 7:2, p. 55-56.

ICHIHARA K. (2004), « The Store Format Systems and the Operational Variables for Effective Strategy in Competitive Pachinko-Hall Business: How to Obtain the Patronage and to Survive in the Full-Grown Market », Bulletin of Tokai Gakuen University, 9, p. 61-94.

Japan Productivity Centre (2013), White Paper on Leisure 2013, Japan Productivity Centre, Tokyo.

JOHNSON DAVID T. (2003), « Above the Law? Police Integrity in Japan », Social Science Japan Journal, 6:1, p. 19-37.

MANZENREITER W. (1998), “Time, Space, and Money: Cultural Dimensions of the Pachinko Game”, The Culture of Japan as Seen Through Its Leisure, S. Linhart and S. Frühstück (ed.), Albany, NY, State University of New York Press, p. 359-381.

NAITO Y. (2000), « The Power of 20 Trillion Yen: the Anatomy of the Pachinko Industry », Nara University of Commerce, p. 55-60.

PLOTZ D. (n.d.), « Pachinko Nation », Japan Society, Retrieved August 6th, 2012, from http://www.japansociety.org/pachinko_nation.

RICHIE D. (1992), “Pachinko”, A Lateral View: Essays on Culture and Style in Contemporary Japan, Berkeley, Stone Bridge Press, p. 226-235.

SIBBITT ERIC C. (1997), “Regulating Gambling in the Shadow of the Law: Form and Substance in the Regulation of Japan’s Pachinko Industry”, Harvard International Law Journal. 38, p. 568-586.

SEDENSKY ERIC C. (1991), Winning Pachinko: The Game of Japanese Pinball, Yenbooks, Ebook.

SCHULL NATASHA D. (2012), Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas, Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press.

TAKIGUCHI N. & ROSENTHAL R. J. (2011), “Problem Gambling in Japan: A Social Perspective”, electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 11:1.

TANIOKA I. (1998), Pachinko and Japanese Society: Legan and Socio-Economic Considerations, Osaka, Institute of Amusement Industries, Osaka University of Commerce.

TOBIN J. (Ed.) (2004), Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon, Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press.

Resources

How to play pachinko (from Pachinko-Play.com): http://www.pachinko-play.com/en/how_to/playp/rent.html

History of Pachinko (from Pachinko Planet): http://pachinkoplanet.com/zencart/index.php?main_page=page&id=2

Places to buy pachinko machines:

Pachinko Portal: http://pachinkoplanet.com/zencart/index.php?main_page=index&cPath=1

E-Bay: http://www.ebay.com/sch/i.html?_nkw=pachinko+machine

Vintage Pachinko: http://www.vintagepachinko.com

For newer machines: http://www.akimono.com/

Dr. Geoffrey Martin Rockwell is a Professor of Philosophy and Humanities Computing at the University of Alberta, Canada. He has published and presented papers in the area of big data, textual visualization and analysis, computing in the humanities, instructional technology, computer games and multimedia including a book from Humanities Books, Defining Dialogue: From Socrates to the Internet and a forthcoming book from MIT Press, Hermeneutica: Thinking Through Interpretative Text Analysis. He is collaborating with Stéfan Sinclair on Voyant Tools (http://voyant-tools.org), a suite of text analysis tools, and leads the TAPoR (http://tapor.ca) project documenting text tools for humanists. He is currently the Director of the Kule Institute for Advanced Studies.

Keiji Amano is associate professor of Cultural Economy at Seijoh University (Faculty of Business Administration) in Japan. His research interest is the utilization of digital technology from business and educational point of view. Currently he is working on the practical use of serious games in higher education, and Japanese local amusement (like pachinko) and its business environment.

Notes

[1] The other forms of gambling include the lottery, betting on soccer, horse racing, motorboat racing, motorcycle racing, and bicycle racing. You also find a form of video slot machines in pachinko parlours.

[2] See for example the Japan Productivity Center’s White Paper on Leisure 2012 or Takiguchi & Rosenthal (2011).

[3] Think of franchises like Pokémon that started as a game, but also involves cards and cartoon series. See Tobin, 2004, for a collection on the global Pokémon phenomenon.

[4] For a more detailed English history of Pachinko see Pachinko Planet’s “History of Pachinko”, http://pachinkoplanet.com/zencart/index.php?main_page=page&id=2

[5] See, for example, the YouTube video showing Zero Tiger by Heiwa, considered the first hanemono type at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kXTBYw5Y2X8. Note how the wings open and close. When open they let in more balls.

[6] Pachinko Play.com (http://www.pachinko-play.com/) has diagrams in their glossary that explain how to play.

[7] Johnson (2003, 30 footnote 14) concludes that the “police seldom ‘crack down’ on pachinko because the system’s benefits are too significant for police to do without.” (Emphasis in the original.)