John Szczepaniak

The history of Japanese video games is poorly documented outside of Japan. Writings in English often focus exclusively on console history, specifically with a preference for Nintendo. Despite the Japanese game culture being highly influential on games around the world (and vice versa), there is a scarcity of English-language interviews with Japanese developers. It’s important to document this history now, since developers age and pass away, and the technology they built decays and ceases to function.

Keywords

Video game, history, Japan, computers, untold

*****

There is a noticeable lack of English language interviews with Japanese video game developers. There is a lot of great interviews with American and European developers, and a lot of history books on the Western side of things; for example, Tristan Donovan’s REPLAY, in addition to Steve Kent’s The Ultimate History of Video Games. But for a Japanese focus, there is almost only Chris Kohler’s book Power Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life, or a catalogue of a Famicom exhibition by the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. There is also a few magazines, such as GameFAN or Retro Gamer, or websites, such as Gamasutra or other fan sites, which will sometimes run very short interviews.

To rebalance the situation, I flew to Japan and interviewed over 70 developers. I published a book, The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, containing 36 interviews, with a further two volumes planned to make use of the remaining material.

When Japanese interviews do happen in magazines or on websites, they tend to be prosaic and safe. There’s only so many times one can read someone asking Shigeru Miyamoto:

« So, tell me about giving Mario a cap because you can’t draw hair. »

« Well, I gave him a cap because I can’t draw hair! »

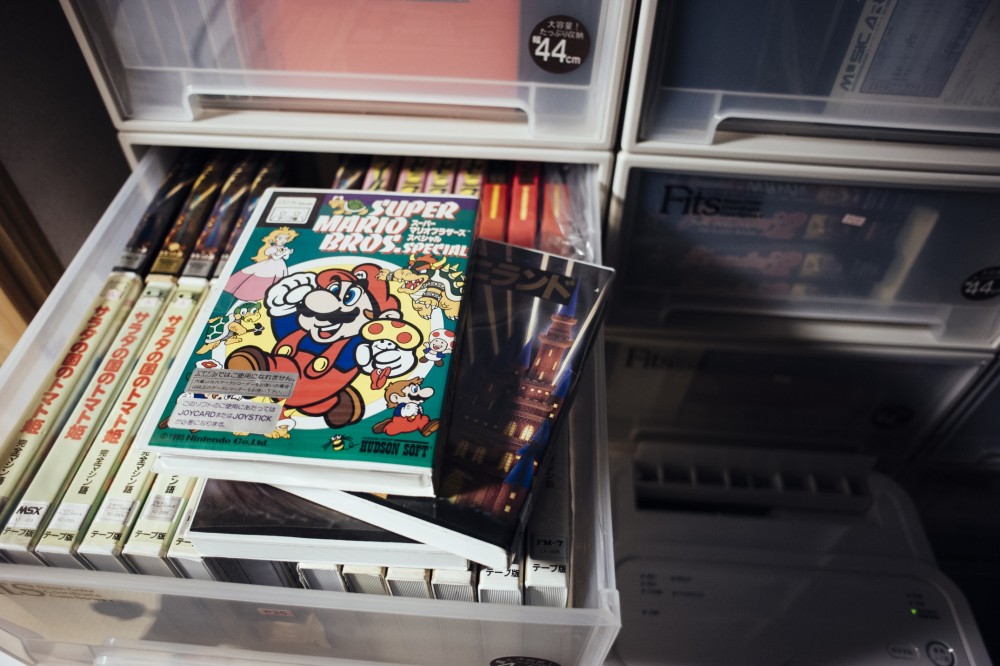

Personally, I don’t have any interest in anything Mario related, unless it’s something I have never heard before. No one ever asks Miyamoto about Hudson Soft’s unique adaptations for the PC-88 computer, as pictured left. This photo is from the Game Preservation Society in Japan, which has over 10,000 original games archived, in storage, including things even Japanese collectors don’t know about. I interviewed the producer on Super Mario Bros. Special for PC-88: Mr. Takashi Takebe.

Personally, I don’t have any interest in anything Mario related, unless it’s something I have never heard before. No one ever asks Miyamoto about Hudson Soft’s unique adaptations for the PC-88 computer, as pictured left. This photo is from the Game Preservation Society in Japan, which has over 10,000 original games archived, in storage, including things even Japanese collectors don’t know about. I interviewed the producer on Super Mario Bros. Special for PC-88: Mr. Takashi Takebe.

Hudson no longer exists, as its staff have all moved on, but this gentleman was easy to get hold of in Hokkaido and very happy to talk. He also created Famicom BASIC and the original Princess Tomato in the Salad Kingdom game, among other things. Why have we never seen a roundtable talk with him and Mr. Miyamoto on the Hudson adaptations of Mario? The games are fascinating – Hudson’s Mario Bros., with the POW block, is legitimately better than Nintendo’s original. Super Mario Bros. Special isn’t as good as the original, but it’s a weirdly hypnotic remix.

Both of these reasons – lack of interviews and safe content when they occur – are due to the language barrier. There’s an enormous amount of interview material in Japan, in publications like GameSide magazine, or the Game Maestro books. For English interviews, however, we have to rely on journalists speaking Japanese, which is rare. Dave Halverson’s GameFAN and Play magazines had a lot of groundbreaking Japanese interviews, some of the best, but Dave had at least two fluent Japanese speakers on staff.

Another option is game publishers doing the translations themselves in exchange for publicity – which is where my second point comes in. A new Zelda title comes out, or a remake of Ocarina of Time, so Nintendo’s PR department rolls out one or two people from development, and if you’re lucky as a journalist, they will translate a few questions into Japanese, and weeks later provide a few answers in English – edited and vetted to make sure nothing outlandish gets out. It is all very tightly controlled. You cannot blame them, since translation is expensive and PR’s job is to generate publicity for product, not document history.

My books circumvented all this by providing on-hand interpreters and bypassing PR entirely, with questions focusing on the obscure, the esoteric, and the generally unknown. There were innumerable setbacks, but actually meeting the developers was easy. Many of these developers seldom have the chance to discuss their careers, and some had never been interviewed. I unearthed a lot of interesting stuff – for example, that Konami was prototyping a game console. They scrapped it, but that project eventually led to the Suikoden series. This information would never come out when going through official PR channels, and it is a significant part of gaming history.

Japanese games have a genuine uniqueness to them, in much the same way American, British and French games all once had distinct qualities (though tend to be more homogenized today). Games may have started in America, but Japan very quickly saw the technology, assimilated it, made some adaptations, and began producing something divergent. Wizardry and Ultima started in the West and captivated a Japanese audience, who then went on to produce an eclectic array of strange RPGs for computers, before Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy cemented the genre tropes, which eventually evolved into RPGs such as Suikoden, mentioned earlier. This dark age of JRPGs, prior to Dragon Quest, is almost like a « Cambrian Explosion« , with strange and exotic experiments.

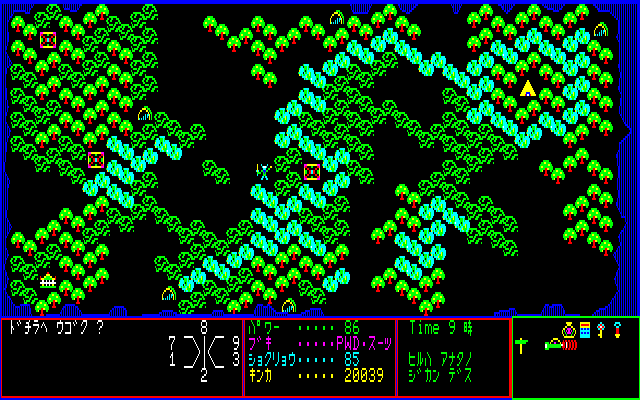

For example, Panorama Toh, released in 1983, is one of the first games from the creator of Legacy of the Wizard on NES, Yoshio Kiya. It is a weird game. There is 3D first-person dungeons in ASCII, a hexagonal grid overworld, you fight tanks and lions and even visit a pornography store. It is also all programmed in BASIC. There were no rules, just fresh creativity.

For example, Panorama Toh, released in 1983, is one of the first games from the creator of Legacy of the Wizard on NES, Yoshio Kiya. It is a weird game. There is 3D first-person dungeons in ASCII, a hexagonal grid overworld, you fight tanks and lions and even visit a pornography store. It is also all programmed in BASIC. There were no rules, just fresh creativity.

I also interviewed Yoshio Kiya, and he described things no one has ever heard before regarding Japanese developer Falcom, notably that the French legends they based Ys and Romancia on, were taken from an illustrated art book the company had. He also revealed that the word « quintet » in the credits of Legacy of the Wizard, has nothing to do with the company Quintet, which split off from Falcom – rather it has to do with the 5 characters, the quintet, which you control in the game: mom, dad, son, daughter and the pet dog. Wikipedia at one point incorrectly cited the word quintet in the credits as signifying that the game had been created by the same-named developer. This is why we need to document facts from first hand sources. Kiya has never done an English interview, and almost never gives Japanese interviews.

I also interviewed Yoshio Kiya, and he described things no one has ever heard before regarding Japanese developer Falcom, notably that the French legends they based Ys and Romancia on, were taken from an illustrated art book the company had. He also revealed that the word « quintet » in the credits of Legacy of the Wizard, has nothing to do with the company Quintet, which split off from Falcom – rather it has to do with the 5 characters, the quintet, which you control in the game: mom, dad, son, daughter and the pet dog. Wikipedia at one point incorrectly cited the word quintet in the credits as signifying that the game had been created by the same-named developer. This is why we need to document facts from first hand sources. Kiya has never done an English interview, and almost never gives Japanese interviews.

Apart from Panorama Toh, there was also Dungeon, by Koei. I spoke with Henk Rogers, creator of The Black Onyx, about Koei and their game Dungeon, and he revealed that Koei backed out of a prior agreement to publish The Black Onyx in order to improve sales of their own game. The politics are fascinating. Koei also made several erotic games, including the karma sutra-style Night Life, a sort of sex guide.

Apart from Panorama Toh, there was also Dungeon, by Koei. I spoke with Henk Rogers, creator of The Black Onyx, about Koei and their game Dungeon, and he revealed that Koei backed out of a prior agreement to publish The Black Onyx in order to improve sales of their own game. The politics are fascinating. Koei also made several erotic games, including the karma sutra-style Night Life, a sort of sex guide.

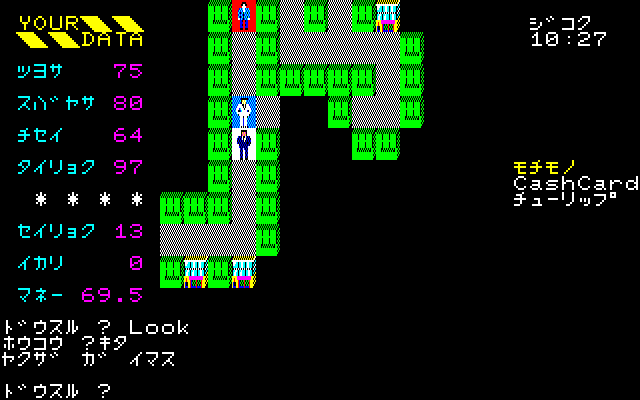

In addition, the company also made Do Dutch Wives Dream of Electric Eels? The game is a sort of sex RPG set in Kabuki-cho, with random battles against the police. I never interviewed Koei, but they are reluctant to discuss these titles and now try to disavow them. Again, this makes documenting and preserving history so important. Companies must not be allowed to write their own history.

In addition, the company also made Do Dutch Wives Dream of Electric Eels? The game is a sort of sex RPG set in Kabuki-cho, with random battles against the police. I never interviewed Koei, but they are reluctant to discuss these titles and now try to disavow them. Again, this makes documenting and preserving history so important. Companies must not be allowed to write their own history.

Japanese games continuously evolved, and Japanese games have special qualities, in terms of audio, visuals, overall aesthetics, historical influences, raw mechanics, narrative structure, originality, and so on. Japanese games are a diverse cultural export of Japan’s. Whether you follow them or not, you are certainly aware of them, and if you play games, you have been touched by them. Mega Man is Japanese, and in-game, it even retains that distinctive anime aesthetic. Cliff Bleszinski of Gears of War grew up playing Japanese games on his NES. The history of Japanese games is intertwined with and influenced so much of what happened outside of Japan – and vice versa. It’s a symbiotic two-way street of continual influence.

While it is a cliche to say, everything most of us know about Japanese games is only the tiniest tip of an expansive, almost impossible to imagine iceberg. The world of Japanese games, how it intersects with other Japanese mediums, the views and contexts of the time, is far more complex than we imagine.

For the majority outside of Japan, their introduction to Japanese games would have been through arcade games, such as Pac-man, or consoles: the NES, later on the SNES and Mega Drive/Genesis, perhaps the PC-Engine, aka TurboGrafx-16, and later the Sony PlayStation, and so on. Each having its own significant developments. But the really interesting part of Japanese gaming history is computers. Only a small percentage of people outside of Japan were lucky enough to play the Japanese computer games localized and ported by Sierra, such as Sorcerian or Silpheed. This raises an important point about historical and cultural context of Japanese games, since almost everything that happens in Japanese games can in some way be traced back to computers; or Space Invaders and arcade games, but that is an entirely different evolutionary topic.

The Famicom, or NES, gets too much credit, both in and out of Japan. It’s very easy to be swept along with Nintendo’s propaganda of it ending up in every Japanese household, and for saving the American games industry after the big video game crash. To fully understand the context, you need to know that the Famicom was released in 1983, and there were less than 10 games released that year. In fact the system didn’t become interesting in terms of software released until 1985, or even 1986. For a long time Nintendo didn’t even allow other companies to release games for it.

Space Invaders came out in 1978, and everyone should know how widespread its popularity was. But here’s the thing, in 1979, in 1982, in 1985, the same story I heard from almost every game developer I spoke to, was that they played arcade games like Space Invaders, they liked games, they wanted to make or play some games at home, so they bought a computer. Often a PC-88, a hobbyist computer. A few actually had expensive imported Apple II computers. I interviewed over 70 developers, and at least 40 started with computers for their home gaming. Maybe only around 5 explicitly said the Famicom. Also, some game companies actually started off selling computers; dB-Soft, Falcom, and others, began business as a retailer of hardware.

Of course, as the 1980s rolled on, and as the Famicom ended up in so many homes, there was indeed a shift to consoles. To give one example: this photo above shows Tokihiro Naito on the left, the creator of the action-RPG Hydlide, an extremely important release in Japan, circa 1984. I know the NES port has an unpopular reputation outside of Japan, but you need to understand the context. It is one of the earliest action-RPGs ever developed, preceded only by Courageous Perseus and perhaps a few other action-RPGs, all on computers. It is also the earliest documented example of a recharging health bar, predating Falcom’s Ys by a few years, and Halo‘s shields by decades. When I interviewed Naito he explained that the later Famicom conversion sold 1 million copies. When adding together all the computer versions, the total sales for those only just matched it at another 1 million. So that’s 1 million sales divided between the PC-88, the PC-98, the PC-66, Sharp’s X-1, Fujitsu’s FM-7, the MSX1, and MSX2, and finally the MZ-2000.

When you consider this, it’s easy to understand why there was such a shift from computers to consoles. Keeping in mind that with computers, no license agreements were needed, plus it was cheaper and easier to commercially publish games. As mentioned previously, there was a kind of Cambrian Explosion of thousands of computer games which eventually narrowed and influenced the console market. It also means: what we experienced in the West, in the Americas and Europe, is only a very small fraction of the overall game culture in Japan. We only received a small fraction of Japan’s console games, which in turn was an evolution of their computer scene. Or arcade titles – but that’s a separate topic from original games played in the home.

As an unrelated aside, Naito’s colleague from T&E Soft, Tetsuya Yamamoto, pictured right, was creator of the Undeadline series of shooters, and also developed a scrolling fighter for the SNES which was never released, called Satellite Man. He gave a detailed explanation and drew sketches, it sounded like a title which would have achieved good sales. This is another reason to speak with developers – there are unreleased games we don’t even know about, and only they can tell us.

THE GAME ARTS EXAMPLE

The most concise examples of everything I have described is the history and pre-history of developer Game Arts. The company is best known for its Lunar and Grandia series of RPGs, and for its older titles like Silpheed and Alisia Dragoon. Silpheed was originally on PC-88, converted to DOS by Sierra, and then later remade for the Sega Mega CD. It was a visually impressive 2D shooting game. An amusing story about Silpheed and Alisia Dragoon – the composers for some of the music on the original computer version of Silpheed were called Mecano Associates. I was speaking with Masakuni Mitsuhashi, composer and sound engineer at Game Arts, who explained:

There were four composers on Silpheed. I did the opening, Kohei Ikeda did the first stage, and then there was Mecano Associates. They found us through a magazine listing for part-time jobs. We got loads of demo tapes. However, one tape was completely blank, no music, and it was their tape. The reason was an error in the recording. I was going to throw it out, but then I called them, just in case, and said, « This is a blank tape. What was the title of your music going to be? » And all of the cassettes at that time had C-60 on them, because it was a 60 minute tape, so they said, « Yeah, the title’s C-60, says it on the tape. » We thought that was a good joke.

So because that was funny, they gave them another chance to send their tape and it was selected. Those same composers later did the music for Alisia Dragoon.

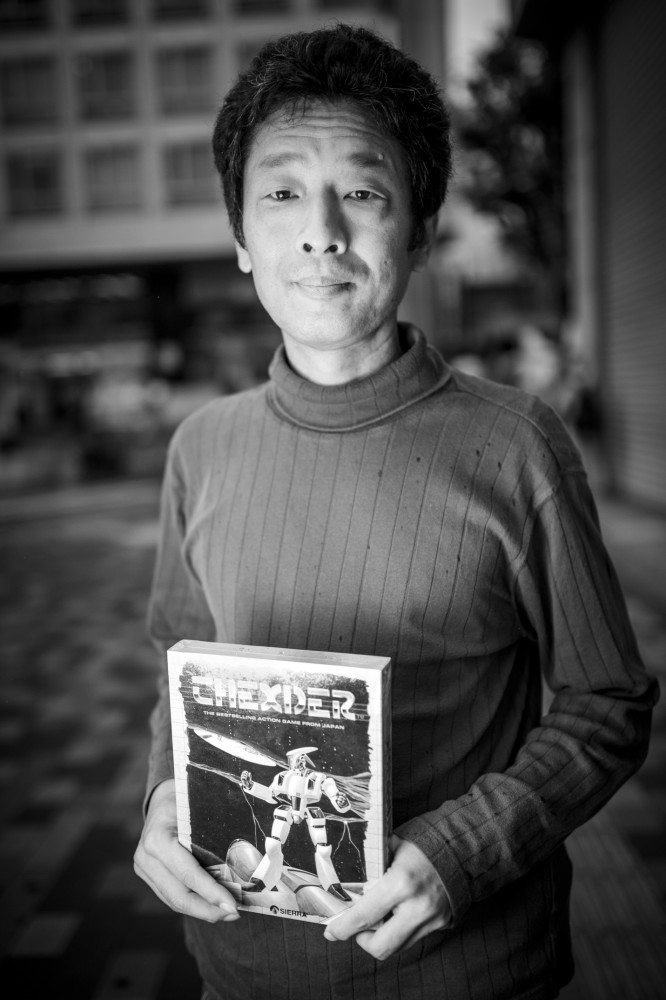

But I digress. Game Arts computer games are actually better known than computer games by other Japanese companies, since Sierra brought over Thexder, Silpheed and Zeliard. Other companies like Enix, Square, Koei, Falcom, and so on, produced a lot of computer games completely unknown outside of Japan.

Here’s a photo of three staff from Game Arts, with a Sierra representative, at Yosemite National Park, when discussing bringing over Thexder. From the left: Tomoyuki Shimada, programmer on Zeliard, who passed away; Game Arts co-founder Takeshi Miyaji, who also passed away; The Sierra representative, Tamara Hyatt; and another Game Arts co-founder, Kohei Ikeda.

Here’s a photo of three staff from Game Arts, with a Sierra representative, at Yosemite National Park, when discussing bringing over Thexder. From the left: Tomoyuki Shimada, programmer on Zeliard, who passed away; Game Arts co-founder Takeshi Miyaji, who also passed away; The Sierra representative, Tamara Hyatt; and another Game Arts co-founder, Kohei Ikeda.

When I spoke with Game Arts co-founder and Thexder creator Kohei Ikeda, he explained the company formed specifically to take advantage of the pending release of a new model of PC-88 computer. The intention was to find success producing three launch titles: Cuby Panic, Thexder and Silpheed. In the end Silpheed was delayed, but the company rode a wave of success with Thexder. This is where it gets interesting, because while Thexder is only known outside of Japan for the DOS release and remake in recent years, it was hugely successful in Japan, a best-seller in 1985 according to Ikeda. As he explained, it was in fact influenced by an inertia platform game for the MSX called Theseus, which is partially where Thexder takes its name from. Theseus in turn was developed jointly by Akira Takiguchi and the aforementioned Masakuni Mitsuhashi, who went under the pseudonym Hiromi Ohba, and they were assisted by Kohei Ikeda, who later made Thexder. In turn, this trio, when making Theseus, state they were heavily influenced by Atari’s Major Havoc arcade game, which was developed by Mark Cerny, who is currently involved with PlayStation work, and who was also the designer on Kid Chameleon and programmer on Sonic the Hedgehog 2 for Mega Drive. Everything is connected to everything else.

When I spoke with Game Arts co-founder and Thexder creator Kohei Ikeda, he explained the company formed specifically to take advantage of the pending release of a new model of PC-88 computer. The intention was to find success producing three launch titles: Cuby Panic, Thexder and Silpheed. In the end Silpheed was delayed, but the company rode a wave of success with Thexder. This is where it gets interesting, because while Thexder is only known outside of Japan for the DOS release and remake in recent years, it was hugely successful in Japan, a best-seller in 1985 according to Ikeda. As he explained, it was in fact influenced by an inertia platform game for the MSX called Theseus, which is partially where Thexder takes its name from. Theseus in turn was developed jointly by Akira Takiguchi and the aforementioned Masakuni Mitsuhashi, who went under the pseudonym Hiromi Ohba, and they were assisted by Kohei Ikeda, who later made Thexder. In turn, this trio, when making Theseus, state they were heavily influenced by Atari’s Major Havoc arcade game, which was developed by Mark Cerny, who is currently involved with PlayStation work, and who was also the designer on Kid Chameleon and programmer on Sonic the Hedgehog 2 for Mega Drive. Everything is connected to everything else.

Game Arts exemplifies the shift a lot of Japanese developers underwent, starting off purely on computers, and gradually moving to working exclusively with consoles. In fact, co-founder Kohei Ikeda left because of this console shift, preferring to work with computers.

Looking at Game Arts, it again reinforces the importance of documenting history. Because even when we discuss the company’s newer, internationally sold games, seldom is it documented how extensively Game Arts outsources. For all four of the earlier Lunar games, the company sub-contracted Vanguard, whose responsibilities grew with each iteration. Vanguard also contributed to Grandia‘s dungeon layouts. Interestingly, the CEO of Vanguard started out developing on the PC-88, influenced by The Black Onyx, and his first RPG had the awesome title, AXIOM: Vessel of Pensance Bait Hides the Hook. Vanguard also worked on rare Sega Saturn hardware. Unreleased, or released only in tiny quantities, it allowed users to browse and shop online, on Rakuten, a sort of Japanese equivalent to Amazon. Japanese game development is a web of unexpected connections.

Let’s look at the AX series

None of this even touches upon the pre-history of Game Arts, which was formed from publishing giant ASCII, the same company co-founded by Kazuhiko Nishi, creator of the MSX. ASCII published magazines and software, and had an inside line on events in the computer world. So the reason why the fledgling staff of Game Arts knew about NEC’s upcoming model of PC-88, was because most had worked for ASCII, producing titles for the AX series of computer games.

One of Game Arts’ main co-founders, the late Mitsuhiro Matsuda, was part of the 2nd publishing division at ASCII and initiated the AX series. To appreciate the significance of the AX series, a sort-of forerunner to Game Arts itself, one needs to know about Japanese computer games circa 1982. There were no game reviews, as we would recognize them, and it was a lawless frontier of amazing games alongside, literally, overpriced garbage. As Mr. Ikeda puts it:

One of Game Arts’ main co-founders, the late Mitsuhiro Matsuda, was part of the 2nd publishing division at ASCII and initiated the AX series. To appreciate the significance of the AX series, a sort-of forerunner to Game Arts itself, one needs to know about Japanese computer games circa 1982. There were no game reviews, as we would recognize them, and it was a lawless frontier of amazing games alongside, literally, overpriced garbage. As Mr. Ikeda puts it:

At this time there were many low quality games. Some were a borderline scam. There were even « games » with 20 lines of BASIC code and a 5,000 yen price tag! There were many terrible business practices. So Matsuda-san’s goal in putting out this AX series was to produce a good quality game at a low price, and to push the industry to improve itself.

Imagine, a full priced game and all you got was an audio cassette and a sheet of photocopied instructions, and once at home it turned out be unplayable. If you look through old Japanese magazines, you’ll find they can be 570 pages of type-in listings and circuit board schematics to build your own, printed in black and white, but there’s no reviews which assign a score or value level to a game. The closest is actually the adverts, printed on glossy paper in color, with descriptions of the games.

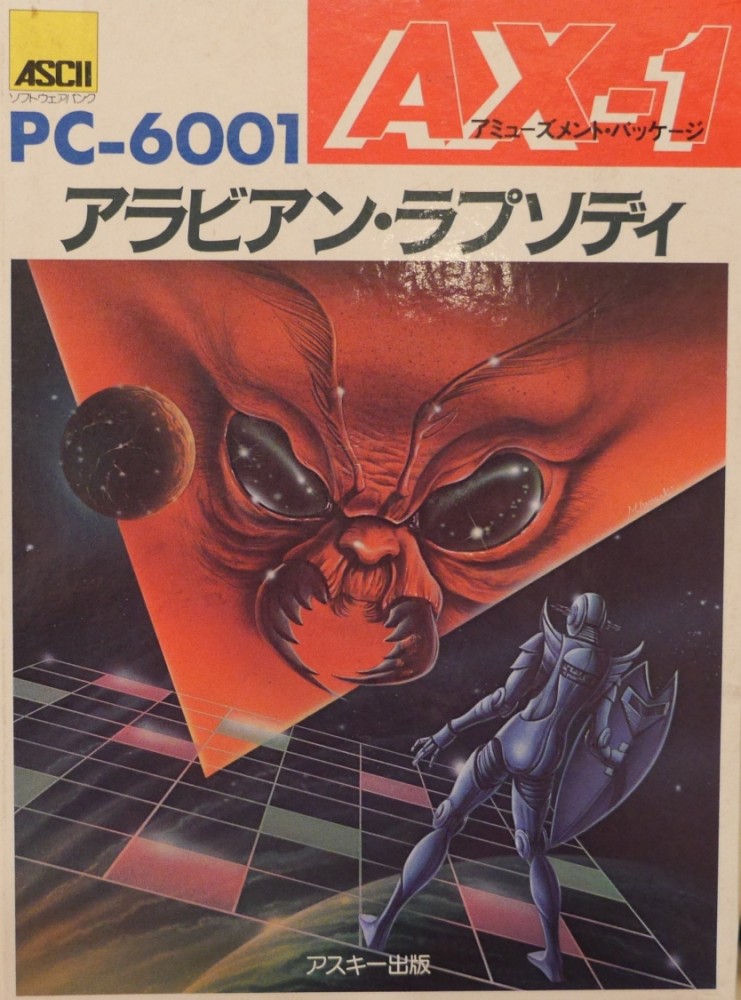

Mitsuhiro Matsuda wanted to change this and raise the quality for Japanese computer games, hence the AX series for PC-6001: high quality, technically accomplished games, often more than one – plus demos – on a single cassette, with a proper instruction booklet, all presented in a sophisticated packaging that mimicked a book with hand painted cover. And cheaper than the competition. It quickly garnered a reputation for excellence.

There were only 10 releases in the AX series, but it brought about a change in Japanese computer games in those early days, with the rip-off software becoming less and consumers expecting more. It is this same spirit that Matsuda then brought to Game Arts, working alongside the same young people, often tech savvy students, who made the AX series. One of them was Mitsuhashi, who explained: « If Matsuda-san had not been around, Game Arts would never have existed. I have no doubt about that. »

The Taito Connection

The pre-history of the AX series is also interesting. Those students who worked on the AX series, a few of them were involved in a Taito deal no one knows about, which helped pay for all of their – at the time – very expensive computers. Hiroshi Suzuki, who was not part of the AX series, signed a contract with Taito around 1980, whereupon he and his university classmates were given use of a private work office, with loan computers, and were allowed to make games. Several of those students would later migrate to ASCII for the AX series. According to Suzuki, after showing these games to Taito they were paid generously, facilitating the buying of more expensive equipment. Taito did nothing with the games. They didn’t request the source code. They didn’t publish the games. They didn’t offer anyone a job. They just gave the students money in exchange for showing them games. It is a strange footnote in the history of the company which made Space Invaders. But there’s no one to ask about it – or what happened to those unreleased games. Taito does not exist, except as a sub-section within Square-Enix. Neither does Hudson exist, since it was absorbed into Konami. Consider this: one of the world’s leading game hardware manufacturers, a pioneer of the CD medium, and they do not exist anymore. This is why there needs to be discussions with developers from the old days – because the industry is so volatile and fragile, we are likely to lose the threads. Hudson staff were easy to track down, such as Mr. Takebe behind Mario, but Taito? I have no idea where to begin to ask about the finished, but unreleased Taito WoWoW console, or the deal they made with Hiroshi Suzuki.

Why we need to document this

We need to document these histories, and we do not have much time. Three figures from Game Arts have passed away: co-founders Mitsuhiro Matsuda and Takeshi Miyaji, plus Zeliard‘s main programmer Tomoyuki Shimada. Their personal recollections and insights will never be known. Ikeda is one of the last direct links. Finding Japanese developers to speak with is not difficult. The misconception that it is difficult only comes from dealing with company PR. Bypass that and the real people behind our games really want to talk, and that’s when you get the gold.

It is not just the people, but the technology is disappearing too. Some say that already, right now, it is too late to salvage anything from those large floppy disks everyone used. Maybe you will find some data, but it is all on the way out. During interviews, I was amazed by stories of development floppy disks so moldy they had an opaque layer of white on them. This photo (on the right) shows a preservationist delicately removing mold from the development disks for the original Thunder Force, as used by TecnoSoft employees.

It is not just the people, but the technology is disappearing too. Some say that already, right now, it is too late to salvage anything from those large floppy disks everyone used. Maybe you will find some data, but it is all on the way out. During interviews, I was amazed by stories of development floppy disks so moldy they had an opaque layer of white on them. This photo (on the right) shows a preservationist delicately removing mold from the development disks for the original Thunder Force, as used by TecnoSoft employees.

Documenting the memories of these creators, and the games themselves, is not just for historical posterity so there can be a paragraph in a book somewhere. There are games which were nearly lost, which set not only precedents, but are extremely fun to play, today, right now, more than 30 years after being made.

The horizontally scrolling Flash Boy for the DECO cassette has no information online. Released in 1981, it sets precedents for multi-directional scrolling, bosses, energy bars, score combos, and more. It is also still entertaining to play today. Like an enhanced version of Eugene Jarvis’ Defender. It exists today only because preservationists tracked down the magnetic cassettes the data came on, repaired and restored them, and made an archive. For a few weeks in Akihabara, there was a working version for anyone to play.

The head of Japan’s Game Preservation Society tells me that he estimates the total number of games released in Japan – excluding amateur doujin titles – from the start until around the modern Windows era, is over 70,000 games. But we are running out of time, both in terms of those who can give us first hand accounts, and the data itself.

We need to be finding, documenting, recording, and preserving these things now.

Black and white photos by Nico Datiche: http://www.nicolasdatiche.com/

John Szczepaniak has been a journalist for over 10 years and has interviewed over 200 people. He is also a novelist and copy editor. He has written for Retro Gamer, GamesTM, Official PlayStation Magazine, Game Developer Magazine, Gamasutra, The Escapist, GameFAN MkII, nRevolution, 360 Magazine, Play UK, X360, Go>Play, Next3, The Gamer’s Quarter, Retro Survival, NTSC-uk, Tom’s Hardware Guide, Insomnia, GameSetWatch, Shenmue Dojo, Pixel Nation, plus others. He frequently contributes to Hardcore Gaming 101, where he helped put together The Guide to Classic Graphic Adventures book, and was managing editor on the Sega Arcade Classics Volume 1 book. He also enjoyed a six month stint as Staff Writer on Retro Gamer and three years as sub-editor at Time Warner. He’s licensed by the UK’s Royal Yachting Association as a naval skipper, and holds a Marine Radio Operator’s license. MENSA certified, speaks Japanese, programs indie games, and brews wine.