Horea Avram,![]()

McGill University

Abstract

My essay discusses the problem of adaptation in installation art practice, considering two theoretical paradigms borrowed from the musical domain: cover and remix. Cover and remix’s de-hierarchizing potential and their capacity to (re)mediate the motifs and (re)inscribe them into a network of cultural exchanges make the two generic concepts particularly relevant to comment on adaptive installation artworks that proposes “forms of repetition without replication” (Hutcheon). I explain the process of adaptation as a form of mutual legitimation: of the source as an authoritative model to be followed, and of the adapted work as a viable product that equally reveres and challenges the original. Thus, instead of social or institutional legitimation, my focus is on the aesthetic mechanisms of transfers (i.e. of adaptation and therefore of legitimation) between different cultural products and their internal functioning and structure—how sources and the derived works act in relation to each other artistically and aesthetically. I claim that cover and remix, as specific expressions of the broader concept of adaptation, propose a creative strategy placed between production and reproduction. In this sense, cover and remix question any assumption of subsidiarity of the adaptation work vis-à-vis the “original” source, and consequently, reject the model of mechanical copy and that of simulacrum as they have been theorized by Walter Benjamin and Jean Baudrillard, respectively. My analysis discusses these particular aspects of adaptation—across different cultural levels (“high” and “low”) and across different mediums—while also commenting on installation’s medium-specificity, more precisely, on what I call its “internal spatiality”.

Pour le résumé en français, voir la fin de l’article

*****

The complex relationships between the model and its reproduction or replica are some of the most debated issues in art history’s long history—a debate that is most often conjugated in terms such as mimesis, representation, copy, simulacra, and their derivatives. My essay is somehow related to these intricate and vast concepts, although I will not discuss them as such. My aim is to see these problems from a more particular angle—the concept of adaptation. More precisely, I will discuss adaptation in installation art considering two theoretical paradigms: cover and remix.

Both terms are borrowed from the musical domain, but they are, I would assert, not only emblematic for our contemporary culture in general, but also very well suited—given their theoretical potential with regard to hybridity, cultural legitimation, and transmediality—for commenting on particular art projects that adapt, borrow, and reuse previous sources. Cover and remix—like most artistic expressions of adaptation—are generally considered to be a sort of subsidiary, if not inferior, work compared to the “original” source from which they derive. To challenge this negative evaluation is one of the main goals of this essay. My assumption is that cover and remix, as specific expressions of the broader concept of adaptation (and of the more particular philosophy of the “re”—recycling, reenacting, recuperating etc.) entail a creative strategy that is placed between production and reproduction. In this sense, cover and remix equally reject the model of a simple “mechanical reproduction” (type Walter Benjamin) and the theoretical account of the simulacrum as it was formulated by Jean Baudrillard. Cover and remix’s de-hierarchizing strategies are, in some ways, related to the theory and practice of translation and intertextuality, but the dialogic relationship they establish between different “texts” (read sources), is nevertheless quite particular, as our examples will prove. Moreover, if the installations discussed here make use of preexisting forms that extend across different mediums, they remain, I claim, different as artistic approaches from other comparable “citational” practices, such as appropriationism and collage. My analysis discusses these particular aspects of adaptation, while also commenting on installation’s medium-specificity, more precisely, on what I call its “internal spatiality”—a feature with profound implications for assessing installation art’s character in general, but also with particular relevance in theorizing adaptation in installationist circumstances.

Adaptation: terms of use

Installation art is defined by most authors (1) as an arrangement of elements in space that creatively activates location (site-specifically), objectual meaning, and viewer’s spectatorship. Aside from these aspects, another defining element (which, however, remains largely unaddressed in the theoretical writings of the field) should be considered when assessing installation art’s complex nature, especially in what concerns its aesthetic dimensions—internal spatiality. The latter represents the space that structures the body of the installation; it is the physical and phenomenological presence of the space that configures the composition, and which assures installation’s functionality, both viewer- and site-specifically. Internal space is the working material for installation artists in the same way as the objects and the context—it is installation’s infrastructure. Internal space permits the viewer’s perambulation among and around the objects, and therefore introduces a perceptual dimension in time. In this sense, it can be said that internal space is a spatialized temporality, and it is important to remember that time is the essential dimension of music (Whitney 1991, 599). In both music and installation’s aesthetic economy, the interval plays a crucial role: in music, the sound (played by an instrument, emitted by a voice, or present in the form of a sample of a previous recording) and the rest (i.e., an interval of silence) have the same value and equal importance in constructing the piece. Similarly, internal space is the necessary interval that assures installation’s internal coherence; it is what makes installation a plausible and meaningful construction.

Internal space is therefore not simply a gap or an empty space, but rather the meaningful intermission between the objects and the viewers of a specific coherent ensemble. Its “internality” is thus defined in relationship with the entire composition of the installation, and it has a different “aesthetic quality”, or rather aesthetic role, than what can be called “external” space, i.e., what lies beyond the “limits” of an installation. Of course both terms—internal or external—are relative and there is no way we can speak about installation as a clearly framed entity. Installation’s site-specificity would contradict precisely such a claim. However, installation—as a spatial arrangement of objects, as a “scenography” built with real materials—can be seen as a reality under specific (i.e. aesthetic, cultural, social, political) conditions. In this sense, installation is a “theatrical space” in which, as Mieke Bal explains, “the object of cultural analysis performs a meeting between (aesthetic) art(ifice) and (social) reality” (2002, 97). Or, to put it differently, installation is a mise-en-scène, described by the same author as “a differently delimited section of fictional time and space” (Ibid.). Internal space is therefore an inner component of this mise-en-scène, integrated into and which integrates the surrounding environment

To better understand the role of internal space in the adaptation process across genres and artistic expressions, we should briefly describe the two generic concepts. Primarily applicable to pop/rock music, cover is described in general as a rendition of a previously recorded song played by musicians in order to bring a tribute to the original artist(s), or to draw in audiences eager to hear a recognizable song; by covering a familiar tune, a band can increase its chance of success, and at the same time, can win credibility by confronting the new version with the original song. As media theorist George Plasketes puts it:

The essence of the cover song may be located in the sense of heritage that the form harbors, preserves, references and reveals. Like any adaptation, the cover song points to the past and profiles its predecessor. As one of music’s major forms of intertextuality, covers are not only immersed in history, they recognize, recite and reshape the past (2005, 157).

A remix is basically a combination of different sound sources (such as entire songs, musical fragments, noises, vocal interventions etc.), assembled into a new entity using the techniques of audio editing (analog or digital). A remix can have different degrees of complexity, from a simple reconfiguration of a track’s existing elements (especially in the early stages of remixing practice), to a multilayered musical tissue that introduces a large variety of quotations, very often reworked and altered. The remix is therefore (or rather it was, at its early stage of development) a radical and creative way to question values such as uniqueness, authorship, originality and copyright; it is a sonic collage opened to continuous reconfigurations, and therefore able to defy any fixed categories. When mixing live, a DJ erases the border between composition and interpretation, between composer and performer. “In the mix, creator and re-mixer are woven together”, as one of the most important artists/theoreticians of the remix, Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid points out (2004, 351). It is useful to mention that although the terms “cover” and “remix” made their name in the pop-rock field, the practices of covering whole compositions and melodic segments, or remixing tunes, are also quite frequent occurrences in the realms of “symphonic music” or jazz, even if, certainly, the means and the destination are most often different. What is important though is to see them in a larger context—as different expressions of the same strategy of adaptation.

Adaptation is an old and constantly present creative format that is motivated by a desire to preserve, replicate, and develop a previous artistic act. Adaptation always defies categories and confronts the limits: it is typically cross medial and fundamentally de-hierarchical; it is, as Linda Hutcheon writes, “a form of repetition without replication” (2006, xvi). Adaptation is therefore a complex entity, a palimpsest that should be seen neither as an inferior work, nor as an absolutely autonomous endeavor, but as a complex product and process of transferring, recoding, repeating, and reviewing elements from one or many sources to a different destination. Simply put, adaptation is a “deliberate, announced and extended revisitation of prior works” (Hutcheon 2006, xiv). In this sense, the process of adaptation is a form of mutual legitimation: of the source as an authoritative model to be followed, and of the adapted work as a viable product that equally reveres and challenges the original. This is precisely what the works discussed here propose: a mutual legitimation across different cultural levels (“high” and “low”) and across different mediums. It is important to mention that the institutional or social legitimation—that is, how adaptation is legitimized by the institutional authority or social consensus—is not the point here. My focus is rather on the aesthetic mechanisms of transfers (i.e. of adaptation and therefore of legitimation) between different cultural products, and their internal functioning and structure—how sources and the derived works act in relation to each other artistically and aesthetically. In other words, how the motifs are (re)mediated by the new works, once (re)inscribed into a network of cultural exchanges.

In what concerns the terminology, it should be mentioned that if, for my investigation, I adopted two terms from the musical domain, it is neither to simply apply a set of concepts from one domain to another, nor to reflect a need to legitimize installation as a visual art form, via another cultural field. This is rather motivated by “logistic” needs: the concepts available in the visual arts vocabulary, which are potentially suitable to commentate on the installations exemplified here (terms such as copy, simulacrum, appropriation, collage), are in fact not entirely adequate to assess the particular aspects of the adaptation process proposed by these installations.

The “samples”

The first three examples of artworks are reinterpretations of established cultural or popular benchmarks, hence, their connection with the “cover” model:

– Stonefridge: A Fridgehenge (illustration 1), by Adam Jonas Horowitz, (started in 1996). This work is an all-refrigerator recreation of Stonehenge, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The artist describes it as a “monument to consumerism and the hubris of man,” constructed from approximately 200 discarded refrigerators. The image of the model is still recognizable, even if the objects that construct the ensemble are not robust stones, but fragile appliances; it is therefore the internal space (i.e., proportions, arrangement, display) which makes Stonefridge a recognizable cover of the well-known megalithic monument.

Illustration 1: Adam Jonas Horowitz, Stonefridge: A Fridgehenge, 1996-2000.

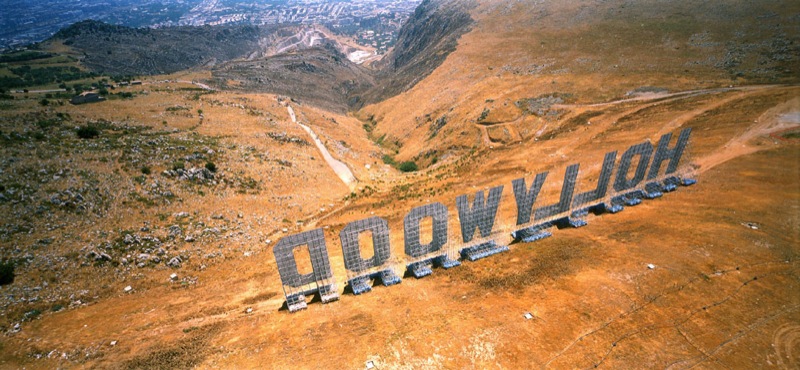

– Maurizio Cattelan, Hollywood (2001) (illustration 2). This is a replica of the Hollywood sign, installed on the hills of Palermo, Italy, for the 49th edition of the Venice Biennale (nine giant letters, 170 meters long, 23 meters high). If objects (the letters) and internal space (the arrangements of objects) follow the same syntax as the original Hollywood sign, the context is radically changed. The famous word reigns with the same proud arrogance as on its original Californian hill, but now as a cover version in a remote and not-so-cinematic environment.

Illustration 2: Maurizio Cattelan, Hollywood, 2001.

-Ilya Kabakov, School No. 6 (1993) (illustration 3). The work is hosted by the Chinati Foundation, in Marfa, Texas. The installation occupies an entire building, subdivided into rooms, plus the courtyard. The work remakes a typical Soviet village school, now abandoned and in a state of disorder. The rooms are filled with desks, bookcases, glass cabinets, notebooks, faded posters, flags, and emblems; the walls are painted with a peeling coat of “institutional green”; in the courtyard, the grass is overgrown. The material ingredients and their spatial placement (or, in other words, the internal space) recreate an environment that tells a story from another space and time. A Soviet-style school—emblematic for certain parts of Europe in a certain period of time—is now reconstructed as a cover version in an American location, as a counter-homage to a traumatic era.

Illustration 3: Ilya Kabakov, School No. 6. 1993.

The next group of works proposes artistic solutions based on fragmentary citations (not unlike the DJ working paradigm), therefore the association with the “remix” model:

– Bus Stop (1999) by Darren Almond (illustration 4). The work consists of two bus shelters installed opposite to each other in a gallery; the indoor space seems too small to accommodate the unusual (obviously outdoor-specific) objects. Their practical role is now undermined by a poetic logic that refers to time, duration, and the experience of space. The work is a kind of illustration of a “primitive” remix, in the sense that it proposes a simple reconfiguration of the available elements into a different composition and another timeframe.

Illustration 4: Darren Almond, Bus Stop, 1999.

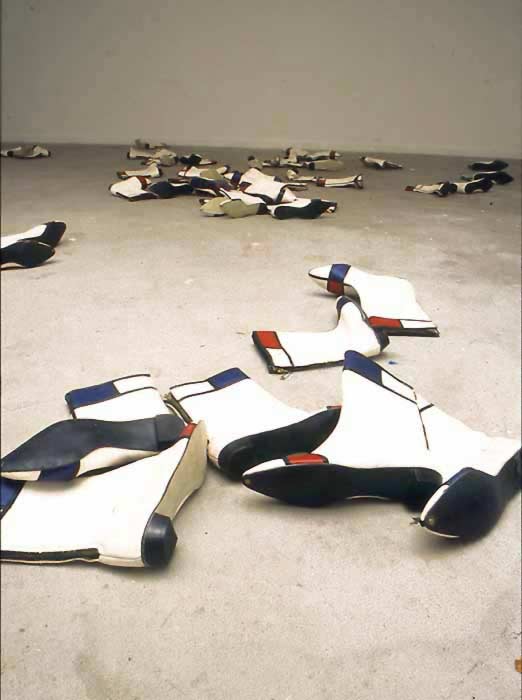

– Sylvie Fleury, Mondrian Boots, (1992, 1995) (illustration 5). Thirty pairs of boots decorated with Piet Mondrian’s painting prints are arranged in a floor composition. The work remixes items of the Modernist repertoire (the unmistakable Mondrian geometrical patterns) with pedestrian objects now reconverted for artistic purposes. The visual “samples”, i.e. the recognizable icons, are not autonomous images anymore, but rather ordinary ingredients incorporated in the “dub mix” of the installationist environment.

Illustration 5: Sylvie Fleury, Mondrian Boots, 1995.

– Michelangelo Pistoletto’s, Venus of the Rags, (1967, 1974) (illustration 6), is an emblematic work of the Arte Povera period, but still exhibited today in different versions. It consists of a clay mould (or a marble copy, in the later version) of a classical Venus (2) plus rags thrown in a heap. Like the previous example, this work features and revolves around a recognizable artistic motif. In the mix, Venus is, at the same time, subverted and reclaimed; it becomes a “sample” (3) assimilated into a different visual entity—a precarious yet compelling new composition.

Illustration 6: Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags, 1967.

“Re”

Since the 1980s, American [and Western European] culture has been operating on “Re” mode control. This cultural condition (…) is an endless lifestyle loop of repeating, retrieving, reinventing, reincarnating, rewinding, recycling, reciting, redesigning, and reprocessing. Reverse gear rammed in maximum overdrive. Creators and audiences alike are revisionaries, infatuated with the familiar and wired with all access passes to the antecedent, reconsidering, re-examining, reinterpreting, revisiting, and rediscovering the world through replays and reissues, reruns and remakes. What goes around comes around. And ‘round again. (Plasketes 137-138).

These remarks are particularly significant for our discussion since all the works exemplified here are, in one way or another, artistic manifestations of the “Re” culture. However, two critical observations are called for: one being that the “Re” culture has operated since long before the 1980s. Revising, recycling, combining, and reconfiguring an ample variety of references is at the heart of equally early modern art (see the collage and ready-mades), the sixties’ Nouveau Réalisme or Pop-art, and of the more recent sampling culture. The other observation is that the process of reclaiming a source is not exclusively drawn in anterior-posterior logic—that is, a retro artistic practice that necessarily works with previously established models—but it can also work on a horizontal plane across various mediums, for example relating “high art” practice with the contemporary production of “greatest hits” in popular culture. In this sense, we can place this philosophy in a larger aesthetic and historical perspective, one nourished by something that could be identified as a “Pop sensibility”. Indeed, working critically with models (old or new) that are external to art means, in fact, to act alongside that “popular-art to fine-art continuum,” as the godfather of Pop-art, critic Lawrence Alloway, once formulated. Nevertheless, any association with Pop art or other artistic moments should not be taken restrictively. The adaptation process and its mechanisms of legitimation operate above strictly defined genres, movements, or mediums: at stake is the idea of evaluating the fluctuant, technically-defiant nature of the artistic strategies that pay a deconstructive reverence to some established motifs. This is why the examples given here are not all recent works, nor are they typologically similar: they were chosen precisely for their efficiency in illustrating an idea.

Within these working parameters we can identify, for example, the DJ mixing “behavior” (however different it might be from the installationist practice in terms of the tools and sources employed and aims). Freely combining one layer of a tune (e.g. the rhythm section or a backing harmony) with one or more parts of another song, the DJ is able to create new hybrid melodic sequences with different aural dimensions. Likewise, a cover musician is open to permanently revisiting not only the repertoire, but also the manner of the reinterpretation. In this sense, cover musicians and DJs share with the installationist artists—regardless of the differences of their discursive frameworks—the same openness in front of the sources they are using in their work. For these musicians, the tune, the song, or the break (that is, the segment of music) has always been there—it just needs to be exploited in a new manner. Similarly, for the artists discussed here, the motifs—either celebrated artworks, famous popular images, or obscure mnemonic objects—are part of an open and accessible “cultural reserve”; it seems that all the artist needs to do is to select the motifs and reinscribe them into a new subjective discourse.

Certainly, there is no such thing as a neutral source. Every motif enters into the mix carrying an entire cultural, historical, and political load. Referring to the idea of remix as a locus of cultural exchange, musician and essayist Brian Eno writes:

What’s interesting is this idea of people using as their materials things that are not neutral. More and more, artists are working with materials that are already culturally charged. That’s different from, say, squeezing cadmium red from the tube: what you’re doing is squeezing out Cézanne from the tube. You’re squeezing out something that already has loads of cultural resonance in it (2002, 17).

Thus, a remix artist is not an innocent user of the sources. He/she is an informed but subjective mediator whose mentality comprises nostalgia, irony and connoisseurship, as Christoph Grunenberg comments (2002, 5) about the DJ practice. To appropriate different sources and to engage them creatively in the remake is basically a “bibliographical” endeavor. One with profound consequences.

Between production and reproduction

The main consequence of the practice of freely borrowing and recirculating sources is the undermining of established values such as originality, uniqueness, authorship and copyright (4). Stonehenge, Mondrian, the Hollywood sign, or Venus are no longer considered unchallengeable and unique cultural items (perhaps crowned with the author’s aura and defended by copyright), but simply materials to be “squeezed out from the tube,” which are recruited without restrictions to take part in the new artistic discourse. So, instead of narcissism and hermetic construct, the covers and remixes discussed here rely on proximity and borrowing, on free reference and intertextual commentary.

Of course, there is a certain sense of secondariness that the adaptive enterprises have with regard to the “originals”, however, this is a position that is not necessarily hierarchically inferior. As Hutcheon points out, “an adaptation is a derivation that is not derivative—a work that is second without being secondary. It is its own palimpsestic thing” (2006, 9). Thus, what is the ontological status of this “thing” vis-à-vis other creative processes? The answer is that, being generative and derivative products/processes at the same time, cover and remix function as creative and interpretative forms/acts situated between production and reproduction. They assume the equal possibility of originating and reconfiguring existing artistic forms, and they assure their authors the quality of being conceivers and conveyors at the same time, that is, equally creators of a distinctive (perhaps “original”) discourse and mediators (although not simply reproducers) of a set of established cultural motifs. Authorship is therefore conjugated in these circumstances in terms of both creation and repetition (but, to be sure, not replication).

In this process, both the sources and the adaptations are seen not as terminals, but as networked elements, as open narratives ready to be incorporated and reinterpreted in a new artistic discourse. In a constantly renewable scenario. As Nicolas Bourriaud (2002, 20) very aptly remarks, “The artwork is no longer an end point but a simple moment in an infinite chain of contributions (…). Going beyond its traditional role as a receptacle of the artist’s vision, it now functions as an active agent, a musical score, an unfolding scenario, a framework that possesses autonomy and materiality to varying degrees…” Caught in this constantly changing chain of borrowings and mutations, this type of artwork can outrightly claim neither the status of an intangible, one-of-a-kind aesthetic act, nor the privilege of a market protégée—that is, of a clearly autonomous product; but at the same time, it can assume neither a secondary role as an artistic copy nor a position as a merchandisable duplicate—in the sense of a mere reproduction. Such artwork then appears to be a personal-collective effort situated somewhere between production and reproduction.

Although their working strategy involves a model and a derivate, cover and remix reject—precisely because of their insertive character (between production and reproduction)—the established dialectic original-copy: they legitimize their discourse beyond such a binary logic. As our examples prove, they are not merely copies mirroring the original, nor are they simulations that replace the original—they are independent (yet highly networked) entities that fill in the gap between composing and recasting, inventing and quoting, production and reproduction. If the works discussed here indeed legitimize the originals, they do so not as copies, but as adaptations (i.e. as covers and remixes). Linda Hutcheon is quite clear about this aspect: “(adaptation) is not a copy in any mode of reproduction, mechanical or otherwise” (2006, 173).

So, the first question that arises, given cover and remix’s in-betweenness (their positioning between production and reproduction), is whether the problems of authenticity and authority, that is, the predicament of the “aura” is still applicable in these circumstances. Walter Benjamin and his (too) much celebrated essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical reproduction” might illuminate the problem to some degree. According to Benjamin,

The authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced. Since the historical testimony rests on the authenticity, the former, too, is jeopardized by reproduction when substantive duration ceases to matter. And what is really jeopardized when the historical testimony is affected is the authority of the object (1969, 221).

But, in the cover and remix types of adaptation discussed here, neither authenticity nor historical testimony are jeopardized or, perhaps, completely erased. Stonehenge, the Hollywood sign, the Soviet school, the bus stop, Mondrian, and Venus (i.e., the “originals”) are all present (in one way or another) in the new works, as valid evidences and historical testimonies. What the viewer experiences in the works exemplified here is not a remote image of the things to which installations make reference, but their corporeal-evocative presence, of course now reinterpreted, reformulated, and sometimes ironized. The works reinstall something of the originals’ appearance, they keep something of their “substantive duration” and something of their initial spatial organization. By actualizing the model, these installations conserve, capitalize and reuse the references in a new auctorial statement that refuses a second-hand position as a copy. They are not situations that “would be out of reach for the original itself”, as Benjamin (1969, 221) fearfully warns us about the consequences of mechanical reproduction. Unlike the latter (and contrary to Benjamin’s apprehensions), cover and remix, as adaptive/reproductive strategies, are able to equally reflect, legitimize, and undermine the model together with all its artistic, cultural, historical, social, or political identity. In other words, they are able to equally re-produce the model and to produce a different embodiment of that model, together with its “aura”. Indeed, both the spatial construct and the objectual menu of these installations indicate the presence of “authenticity”, “historical testimony”, and “authority”, more precisely what Benjamin names with a single word, the “aura” of the sources. Moreover, as “originals” themselves, these works are the privileged possessors of a brand new “aura”. However, the presence or the integrity of aura is less important; what is important is to understand the way in which cover and remix challenge existing categories, as well as the modes in which they affirm their double identity as a product and as a reproduction—as a hybrid entity, object and process at the same time.

Another question that should be addressed, given this double status of the cover and remix, is if their adaptive strategy reflects the theoretical model of the simulation. The latter is understood in the sense proposed by Jean Baudrillard (1983, 2), as “the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal”. Referring to simulacrum’s ability to deter the real by its operational double, Baudrillard claims that simulacrum “is no longer a question of imitation, nor of reduplication, nor even of parody” (1983, 4). But this is exactly what our examples are: the installations analyzed here work with imitation (not as mimesis, but as cover), reduplication (the revisitation of established symbols, as adaptation), and parody (the ironic undermining of well known models and the intertextual play between various references). Moreover, according to Baudrillard, simulation is “a question of substituting signs of the real for the real itself” (1983, 4). If the main characteristic of the mechanical copy and of the simulacrum is the idea of substitution—an original replaced by a surrogate, or a sign displaced by another similar sign, respectively—this is not the case with cover and remix. As our examples prove, the original sign is neither replicated nor substituted by adaptation’s sign, but the signs coexist. They legitimize each other symbolically. If “simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance” (Baudrillard, 2), cover and remix involve and call for territorialization, they establish their own territory (or rather originate their own place—a term that is perhaps preferable for its linguistic root: origin, original, etc.): Stonefridge does not take the place of the Stonehenge by copying or simulating it; Catellan’s Hollywood has a parallel existence with the original—their signs are different: one is a slogan, the other is art, one is Hollywood, the other is Hollywood (with italics), etc. Moreover, it is not without significance to observe, following Deleuze and Guattari in “Of the Refrain”, that the act of territorialization is also a characteristic of the rhythm. Given that our leading notions are primarily musical terms, the equation territorialization–rhythm-cover and remix seems to function at all levels: “territorialization is an act of rhythm that has become expressive, or of milieu components that have become qualitative. The marking of a territory is dimensional, but it is not a meter, it is a rhythm” (Deleuze and Guattari 2003, 315). And what is the internal space of an installation, if not a rhythm, an expressive articulation of the objects in the ensemble (“territory”) of the installation? And, what is an installation, if not the literal manifestation of territorialization, that is, a taking into possession and a fictionalization of a portion of reality?

Translating the world as cover

Yet the idea of territorialization should not be seen exclusively in spatial terms. It can also be—at a more abstract level—the process of designating a zone of conceptual transfers, of mediations and transcultural adaptations—in other words, an act of translation. As an expression of adaptation, translation is not a mot à mot mirroring of the original but rather a transfer of meanings between the two poles—between languages, cultures and time periods. This is precisely what cover is: a transmutation, a translation, a transfer of substance and of spirit from one protocol to another—between Stonehenge and Stonefridge, between Hollywood and Hollywood, between a certain School No. 6 and School No. 6. As Linda Hutcheon rightly remarks:

Just as there is no such thing as literal translation, there can be no literal adaptation. (…) Transposition to another medium, or even moving within the same one, always means change or, in the language of new media, “reformatting”. And there will always be both gains and losses (2006, 16).

Indeed, as the first examples demonstrate, some of the initial meanings of the sources to which they refer are at the same time strengthened and undermined—as with all translations or covers, the distance between the source and the adaptation is always negotiable. Speaking about the creative and unrestricted negotiation with the original in translation, Walter Benjamin writes in his essay “The Task of the Translator” (1996, 261): “A translation touches the original lightly and only at the infinitely small point of the sense, thereupon pursuing its own course according to the laws of fidelity in the freedom of linguistic flux”. This is also what George Plasketes suggests (2005, 150) when he describes the musical cover.

The process of covering a song is essentially an adaptation, in which much of the value lies in the artists’ interpretation. (…) Measuring the interpreter’s skill, in part, lies in how well the artist uncovers and conveys the spirit of the original, enhances the nuances of its melody, rhythm, phrasing, or structure, maybe adding a new arrangement, sense of occasion or thread of irony.

So, to cover or translate an original is not to remain in a fixed framework of tedious faithfulness, but to speculate and paraphrase, to interpret the work with an equal sense of fidelity and freedom. See Stonefridge: while it preserves some of the formal appearance (the internal space, the general shape) of the original monument, it now turns, tongue-in-cheekly, the stones into fridges and the name into a nickname. Also, if the installation conserves a certain devotional sense, like its sober sculptural predecessor, this time the consecration is directed not to some unknown god, but to the more mundane idea of “consumerism & the hubris of man”. See Hollywood: the word, the slogan, the image is there, exactly like the original, yet something is missing—the arrogance, the context: the Californian “Hollywood” is now subverted by its Italian jovial “double”. See School No. 6: the space, the objects and their arrangements indeed look like those of a genuine Soviet school; the work is precisely that type of environment, but its meaning is sarcastically interpreted, or rather inverted to suggest both nostalgia and a sense of exorcism.

It is this free interpretation and the concrete value given equally to the original and the adaptation that makes cover a different species from appropriationism. As it was described by its practitioners, Appropriationism is basically a critique of representation: the appropriationist artist considers that we are living in a world of abstract signs that cease to refer to a tangible reality. In this universe of simulacra, there can be no copies, since there are no originals; art disappears as practice, but it reappears as sign. Sherrie Levine, one of the most prominent appropriationists, won international fame by re-photographing, among others, Walker Evans’ Great Depression photographic documents from the 1930s and exhibiting them as such. Her statement was clear: “pure” simulation, the altered documentary value of a photograph, a copy of a copy, no “aura”, plus a feminist approach to patriarchal masters, etc. (5). While for appropriationism the issue is to decontextualize an object and recontextualize it (with minimal or rather no modifications), for the practice of covering, or more precisely for the practice of translating an original source into a cover, the concerns are quite different. The art object (either the original or its cover) is not seen as an absolute commodity and its existence not as a replaceable sign. On the contrary, to cover means to subjectively (but not blindly) activate the original source without substituting it; to provoke it without proposing a surrogate. If appropriationism is based on replacement, cover is grounded on re-enactment. The cover is neither a mere copy of the work to which it refers, nor a “tricky” simulation, but a reinterpretation of the original, a reterritorialization with comparable means; it is a repetition without the stigmata of a lesser double. Again, it is worth it to note the important role internal space plays in this re-enactment: in Stonefridge, it is the internal space—which suggestively follows (although not precisely) the same pattern as in Stonehenge—which makes the work a recognizable cover; in Hollywood cover, the jingle (i.e. the spatial organization and its “letter”) is recognizable, but it is played in another key, with other instruments, in another context, and even if the “lyrics” are the same, the meaning is different; finally, in School No. 6, in a sort of inverse logic, if the objects are the same as in the original score, the “interior design” of the room—or its arrangement (in both a spatial and musical sense)—is the artist’s contribution.

Remixing: the ecstasy of citing

A constant theme in any experiential or aesthetic assessment of an adaptation is the question of what is actually adapted and how. In other words what exactly is produced and what is expectedly reproduced, and how the original source and the new input function together in the alternative narrative. The issues are more complicated when the transfers between the source and the adaptation are instead of homogenous covers, heterogeneous remixes based on a working model grounded in citational strategy. In essence, citational practice relies upon a recurring reference and the use of fragments from various existing cultural contexts that are usually kept separate. Adaptation, in this sense, is an accumulative effort in which different sources coexist and resonate. Post-structuralism made great efforts to explain that all works are actually a mosaic of citations, visible or invisible, obvious or discreet. As Hutcheon very aptly points out: “So, too, are adaptations, but with the added proviso that they are also acknowledged as adaptations of specific texts” (2006, 21). Indeed, adaptation should be seen as a circumstantial “intertextual” discourse and not as a latently citational one. Especially in the case of remix, adaptation is a complex set of regulated interactions in which the active sources are well researched and carefully identified. As always, the degree of familiarity with the model (or the sources quoted) goes hand in hand with our satisfaction in front of the new adapted work. Or, to put it differently, the accomplishment of any process of adaptation (and consequently of the process and the meaning of legitimation) goes hand in hand with the extent to which we recognize and accept the quoted source as “viable”. Like in a DJ audio remix (to be precise, one that uses the samples not only for their formal but also for their citational effect), in the three installations by Almond, Fleury, and Pistoletto the found source with which the artist works is not a nameless, neutral and indistinct entity, but a specific, culturally imbibed element that “holds out an invitation to be used because of its cause and because of all the associations and cultural apparatus that surround it” as composer Chris Cutler writes about the practice of remix (2004, 146). Indeed, the samples of a mix—either sounds, objects or spaces—are carrying with them their original meanings and traces of the previous structure from which they derive (in a word, their “memory”), but once entered into the mix, they do not necessarily preserve their hierarchical position in terms of culture, space and time: Beethoven can stand near a car horn, Mondrian can be attached to a boot. Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid, articulates the same idea in the following terms: “The previous meanings, geographic regions, and temporal placement of the elements that comprise the mix, are corralled into a space where the differences in time, place, and culture are collapsed to create a recombinant text or autonomous zone of expression based on what I like to call ‘cartographic failure’” (2004, 354).

The phrase “cartographic failure” has a particular relevance in this context, precisely for its spatial reference. For what is an installation, if not an “autonomous zone” (a territorialization) where various references collide and merge (especially in our particular examples in which the hierarchical differences in terms of culture, time, space, and geography are defied)? The idea of cartographic failure is at the core of Almond’s work Bus Stop, this time in the most literal sense. While the ready-made objects (the two “samples” of bus shelters) that construct the work have a recognizable appearance, their normal spatial relation, or, in fact, their “rhythmical structure” is beyond the utilitarian logic: the work is an “upbeat” version of an imaginary bus move between two stops, now situated one in front of each other. Time is compressed and accelerated according to the subjective fragmentation of space between the two shelters. Both time and space are objectified and processed (like samples in a DJ mixer) in order to fit and serve the new mix. So, internal space is not simply a gap within the whole composition, but an element of order and signification. Like in the other works discussed here, material objects, as well as the space that articulates them, becomes “signs seeking sense”—as Paul D. Miller (2004, 353) remarks about the sound samples—signs that function as an “externalized memory”. They are not neutral elements, but catalysts of memory and significance, and in their new arrangement they can reformulate the data they carry by creating new sets of memories and significances—in the case of Bus Stop, issues related to nostalgia of a particular location, to personal memory and the significance of community and ephemerality.

Take the other example of the remix model: Fleury’s Mondrian Boots. The work combines within its composition radically different sources that all come with their own cultural imprint. But while the work adopts and preserves the specificity and memory of each sample, it resists maintaining the “rank” of the sources in terms of their “high” or “low” cultural provenance. Mondrian Boots, exactly as the title indicates, puts Mondrian’s art and a type of footwear in the same hierarchical position. Art history’s icon of the abstract art now shares the same fate with a casual object. De Stijl becomes simply “style”. The work is therefore a parodic take on the populist use of established iconography, a mapping of feminine concerns and a critique of consumerism. But this remix is also a new spatial (dis)order aimed at disturbing any rigid geometry and parietal display normally imposed by a Mondrian image. Fleury’s floor installation is a formless manipulation of objects and visual patterns that can suggest—musically speaking—something between “These boots are made for walking” and improvisando fragments on a Mondrian theme.

As for Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Venus on the Rags, perhaps its most significant aspect is the desire to de-hierarchize the relations between its main constituent elements: the work combines and adapts in the same score classical moments with everyday objects, precious material with debris, references to master models with the idea of consumption, invention with citation. By deturning (6) Venus as a symbolic monument and remixing her into a new heterogeneous and pedestrian composition, the artist adds new layers of meaning both to the individual elements and to the whole ensemble. Like a sound sample, the goddess in Pistoletto’s work carries “the unique ability not just to refer, but to be; it offers not just a new means but a new meaning” (Cutler 2004, 146); one that is practically open to always renewed possibilities of signification. The originality of this Venus is not the point: the statue is either a plaster moulding (in the 1967 version) or a marble replica (in the 1974 version) of the original Antique sculpture. Like a recorded sound sample, the adapted Venus is therefore not unique—it is subject to infinite reproductions, alterations, and re-edits. As for the composition, like in the other examples above, internal space plays a crucial role: what should have been the “normal” empty space around the sculpture—which would have permitted a museum-like frontal contemplation—is now reduced to a minimal interstice. Moreover, instead of facing the public, the classical beauty is facing the rags. Therefore, Venus is for the contemporary artist not only a way to capitalize on the authority and the prestige of an ancient model but also a way demithyze the same model, to treat it not as a unique and intangible monument, but just as a reiterable piece in a constantly renewable remix.

As the last three examples of remix show, there is something about their internal organization—more precisely their internal spatiality—that makes them different from another set of artistic practices that relies on the conjunction of different sources and references: collage. Itself an expression of hybridity and part of the same “Re” philosophy, collage shares some of the (installationist) remix’s characteristics: it is a multilayered tissue that can introduce a large variety of quotations; by combining different “found” sources together, it questions values such as uniqueness, authorship, originality and copyright. However, if collage is inescapably a closed system, installation is instead essentially an open one: installation’s aesthetic significance resides in its commitment to continuous reconfigurations and therefore to defying fixed categories. If collage relies on flatness and spaceless arrangements, installation art operates with depth, deambulatory spatiality, and theatricality. Unlike collage, installation is a shifting environment with moving borders; it is an active, viewer-inclusive setting; it is, in other words, an open structure.

A legitimate conclusion

This “openness” of the installation is surely an important asset in the adaptive process, especially when adaptation relies on the creative strategies of the cover and of the remix. Thus, as an open structure, installation art as adaptation is able, perhaps more than other artistic means, to “involve both memory and change, persistence and variation” (Hutcheon 2006, 173). As mechanisms that both critically challenge and confirm the (use of the) various cultural sources brought into play, our works, therefore, insist not so much on the idea of the viewer’s immediate involvement (and the effects of the direct spectatorship), but rather on the set of questions the adaptive practice (expressed as installationist covers and remixes) would rise at the conceptual, expressive and cultural levels. A set of questions that becomes an intertextual game of legitimations—between the collective memory and subjective individual approaches, between popular culture and artistic discourse, between the model and the adaptation. In such circumstances, the work is not a self-contained depository of artifacts with a centralized meaning, but a mobile platform of dialogue and transfers inhabited by objects and ideas already informed by previously validated models. And always opened to extensions and re-adaptations. What counts in these artistic arrangements is not the originality (in the sense of primacy), but the meaning; not the uniqueness, but the message the adaptation leaves behind. Moreover, what counts is not the work’s status as production or reproduction, but its subjective condition of being both at the same time.

Notes

(1) See among other examples: Nicolas De Oliveira, Nicola Oxley, Michael Petry, Installation Art in the New Millennium. The Empire of the Senses, London: Thames & Hudson, 2003; Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity, Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2002, Erika Suderburg (ed.), Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000; Julie H Reiss, From Margin to Centre: The Spaces of Installation Art, Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2000. Notably, Claire Bishop remarks that “in a work of installation art, the space, and the ensemble of elements within it, are regarded in their entirety as a singular entity” (Claire Bishop, Installation Art. A Critical History, New York: Routledge, 2005, p. 6).

(2) The Aphrodite of Cnidus (Knidos) by Praxiteles (c.350 BC).

(3) A “sample” is the main working element for the remix artists; it is an analog sound converted into electronic (digital) format, and therefore opened to infinite alterations and multiplications. “Sampling enables such techniques as incorporating prerecorded material in a new composition and is widely used in rock and other kinds of popular music” (See Christine Ammer, Dictionary of Music, New York: Checkmark Books, 2004, 360.)

(4) This is actually the main reproach addressed to musical remixing. On this subject, see among others Chris Cutler, “Plunderphonia”; John Oswald, “Bettered by the Borrower: The Ethics of Musical Debt”; David Topp, “Replicant: On Dub”; Paul D. Miller, “Algorithms: Erasures and the Art of Memory”. All essays published in Audio Culture. Readings in Modern Music, edited by Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner, New York, London: Continuum, 2004.

(5) It is significant to remark here that Sherrie Levine’s work too was appropriated by another artist. In 2001, Michael Mandiberg scanned Levine’s photographs and published them on his websites AfterWalkerEvans.com and AfterSherrieLevine.com. The scanned images are downloadable from the websites, together with a “certificate of authenticity” which can be signed by anyone. “This is an explicit strategy to create a physical object with cultural value, but little or no economic value”, writes Mandiberg on his site. It is tempting to speculate and suggest that Mandiberg’s project is able to put Levine’s photographs in a bizarre position as originals!

(6) This term is proposed here as an English adaptation of the French word détournement, used by Guy Debord and International Situationists to describe the process of juxtaposing printed or film images with a different written or verbal discourse in order to destabilize, reengage and divert the original message and context of the images.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alloway, Lawrence. “The Arts and the Mass Media.” Architectural Design, vol. 28. no. 2 (February 1958): 84-85.

Bal, Mieke. Traveling Concepts in the Humanities. A Rough Guide. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulations. Trans. Paul Foss, Paul Patton, Philip Beitchman. New York: Semiotext[e], 1983.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Trans. Harry Zohn. Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books, 1969.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator.” Trans. M. W. Jephcott and K. Shorter. Walter Benjamin. Selected Writings. Volume 1: 1913-1926. Ed. M. Bullock and M.W. Jennings. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Postproduction. Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World, Trans. Jeanine Herman. New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2002.

Cox, Christoph and Daniel Warner, eds. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York and London: Continuum, 2004.

Cutler, Chris, “Plunderphonia.” Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. Eds. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner. New York and London: Continuum, 2004.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “Of the Refrain.” A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Eno, Brian. Introduction. Remix: Contemporary Art & Pop (exhibition catalogue, Tate Liverpool). Liverpool: Tate Publishing, 2002.

Grunenberg, Christoph. Introduction. Remix: Contemporary Art & Pop (exhibition catalogue, Tate Liverpool). Liverpool: Tate Publishing, 2002.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Miller, Paul D. “Algorithms: Erasures and the Art of Memory.” Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. Eds. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner. New York and London: Continuum, 2004.

Plasketes, George. “Re-flections on the Cover Age: A Collage of Continuous Coverage in Popular Music.” Popular Music and Society. Vol.28, Issue 2 (May 2005): 137-161.

Whitney Sr., John. “Fifty Years of Composing Computer Music and Graphics: How Time’s New Solid-State Tractability Has Changed Audio-Visual Perspectives.” Leonardo, Vol. 24, No. 5 (1991): 597-599.

*****

Illustrations

Almond, Darren. Bus Stop. 1999. Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin.

Cattelan, Maurizio. Hollywood. 2001. Photograph by Armin Linke, Galerie Perrotin, Paris.

Fleury, Sylvie. Mondrian Boots. 1995. Le Consortium, Dijon.

Horowitz, Adam Jonas. Stonefridge: A Fridgehenge. 1996-2000. Photograph by Benjamin Cacchione. Santa Fe.

Kabakov, Ilya. School No. 6. 1993. Photograph by Florian Holzherr. The Chinati Foundation, Marfa.

Pistoletto, Michelangelo. Venus of the Rags. 1967. Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC.

*****

Biographical notice

Horea Avram is currently PhD candidate (ABD) in Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University, Montreal. His areas of research include visual cultures, theory of representation, installation art, (new) media artistic practices and all the relationships between them. His doctoral dissertation is focused on the aesthetics of space and the problem of (re)presentation in Augmented Reality art and technology. He contributes with essays and reviews to various exhibition catalogues, periodicals and online portals.

*****

Key words

Installation art, adaptation, cover, remix, pop culture, space, production, reproduction

*****

Résumé

Cet article adresse le problème de l’adaptation dans la pratique artistique de l’installation, en se basant sur deux paradigmes théoriques : la reprise et le remix. Le potentiel déhiérarchisant et leur capacité à (re)médier les motifs et les (ré)inscrire dans un réseau d’échanges culturels font en sorte que ces deux concepts deviennent particulièrement pertinents pour commenter les oeuvres d’art d’installation adaptatives proposant des « formes de répétition sans reproduction » (Hutcheon). J’explique que le processus d’adaptation est une forme de légitimation mutuelle : légitimation de la source comme autorité à suivre et légitimation de l’oeuvre adaptée comme produit viable qui révère et conteste simultanément l’original. Ainsi, au lieu de discuter de légitimation sociale ou institutionnelle, je me concentre sur les mécanismes esthétiques de transfert (c’est-à-dire de l’adaptation et ainsi, de la légitimation) entre les différents produits culturels et leur fonctionnement et structure internes comment la source et son oeuvre dérivée agissent l’une par rapport à l’autre artistiquement et esthétiquement. Je propose que la reprise et le remix, comme expressions spécifiques du concept plus large d’adaptation, mettent de l’avant une stratégie créative placée entre la production et la reproduction. En ce sens, la reprise et le remix questionnent toutes les suppositions de subsidiarité de l’oeuvre adaptée vis-à-vis la source « originale », et conséquemment rejettent le modèle de la copie mécanique et celui du simulacre, tels que théorisés par Walter Benjamin et Jean Baudrillard, respectivement. Mon analyse traite de ces aspects particuliers de l’adaptation à travers différents niveaux culturels (« haut » et « bas ») et à travers différents médiums tout en commentant la spécificité médiatique de l’installation, plus précisément ce que j’appelle sa « spatialité interne ».